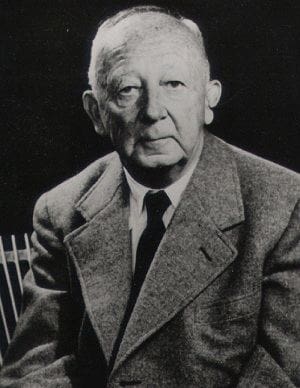

Hans Freyer, a Forgotten Scholar

Hans Freyer’s[i] (1887-1969) name means nothing to young sociologists today, despite the heated debates about his reputation that took place in the second half of the last century. Ralf Dahrendorf, albeit acknowledging Hans Freyer’s intellect, called him a traitor of sociology for his work during the National Socialist era,[ii] while René König considered him a brilliant writer and warned against underestimating his work.[iii] But who was Hans Freyer, why did he arouse such passion some decades ago and why has his name been forgotten?

Hans Freyer was a very important sociologist active in the first half of the 20th century, who played a major role in the development of German academic sociology. Freyer began studying economics, history, philosophy and theology at the University of Greifswald in 1907. He later moved to Leipzig, where he gave up theology and sought a new goal, which became partly philosophy and partly sociology. He obtained his doctorate in 1911, then qualified as a teacher in 1920, and two years later became professor at the University of Kiel. In 1925, Freyer moved to the University of Leipzig, where he founded the university’s department of sociology, which he headed until 1948. Freyer was an exponent of the conservative revolution (or radical conservatism) in Germany in the 1920s and 1930s who, while initially not opposed to the National Socialism, soon became disillusioned with the Nazis and adopted a position of passive opposition. Sadly, his name is now known to few outside Germany, and after the ideological revolt of 1968 he was completely forgotten. This is regrettable as Freyer’s ideas still hold relevance for both contemporary sociology and politics.

Sociology as Wirklichkeitswissenschaft

According to Freyer, sociology has its genesis in the philosophy of history and its original aim is to understand the specific patterns of cultural change by examining the interrelations between past and present. This is necessary in order to enable the sociologist to contribute to the transformation of society, of which he himself is part, and thus has a responsibility towards society. This is why Freyer called sociology Wirklichkeitswissenschaft (reality science). The term is of Weberian origin, but has a very different meaning in Freyer’s thought. For Weber, knowledge of reality science means knowledge of historical reality in its own right. In Weber’s words, ‘…by looking at the interrelationship and cultural significance of certain phenomena, on the one hand, in their present form, and, on the other, by searching for the reasons why they became so historically.’[iv]

The Legacy of Simmel

Culture, in the Freyerian sense, has another very important function, and that is to set collective goals and make the life of the individual meaningful

Freyer has taken much from the work of Georg Simmel, including his understanding of culture. Consequently, he understood it to mean the institutions, beliefs, customs of a society – in other words, all the external constructions of society.[v] In the course of its functioning, society constantly creates tools, concepts and institutions, which always occurs at specific points in history, in order to satisfy particular needs and desires. As soon as an object, institution or concept is created, it acquires “objective value”, it becomes objectified.[vi] The meaning given to objectifications by their creators changes over time and takes on a different meaning. This creates a kind of living tradition that is both connected to life and distant from it.[vii] But this process is shaped by generations, with sons giving new meaning to the tradition of their fathers. This historical continuity in the re-appropriation of culture gives cultural forms or traditions a special meaning for the people who bear them in the present. Culture, in the Freyerian sense, has another very important function, and that is to set collective goals and make the life of the individual meaningful. Tradition thus both stabilises society and provides a meaningful life for its members.

Community, Society, State

As we have already seen, for Freyer, life is fundamentally communal, and so, by necessity, he stood in sharp contrast with contemporary liberal individualism, which holds that individuals exist essentially only as individuals, i.e. they are completely independent of each other unless they choose to associate “rationally” or enter into a “social contract”. However, at the time, it was not only the conservatives who rejected individualism, but the social democrats as well, including Ferdinand Tönnies. Tönnies distinguished between Gemeinschaft (community) and Gesellschaft (society), a distinction that Freyer also adopted. Community consists of organic relations, the result of natural will, of a sense of belonging and of togetherness, whereas society consists of mechanical or instrumental relations, consciously formed and thus the result of rational will. Tönnies experienced the decline of the community and the advancement of society as a loss, because he saw in it the death of solidarity.[viii]

Using Hegel’s dialectic and Tönnies’ concepts (community, society), Freyer divided history into three stages. The first two stages have both positive and negative features, while the third preserves the positive features and eliminates the negative ones.[ix] It is a closed form where there is no conflict between human ends and means. At this point, the individual is fully embedded in the community through language, myth and cult, so that everyone shares a common cultural horizon and there is no high culture. The next stage is society, which is best captured by the concept of domination. A this stage, there are two orders according to Freyer, and social status is based on “blood”. But economy is slowly replacing blood, so that the social stratification shifts from descent to wealth and class society replaces order. The harmony of community is finally broken and the resulting tension creates high culture. Various spheres (politics, economics, religion, art, etc.) are created and increasingly operate according to their own logic, generating constant conflict (Simmel called this the tragedy of culture). As a result, the common cultural horizon and collective meaning are lost. The last stage of this crisis is the state. In this phase, technological, economic and other advantages are preserved, but they are reunited in a totality through the state, thus recreating the lost cultural horizon.

Technology

Freyer believed that technology is not a neutral means, since on the one hand it is a product of society’s attitude towards nature (i.e. habitus), and on the other hand technology is dependent on the aims of culture

For conservatives, technology is usually something of a threat, but radical conservatism has developed a positive attitude towards it. Freyer believed that technology is not a neutral means, since on the one hand it is a product of society’s attitude towards nature (i.e. habitus), and on the other hand technology is dependent on the aims of culture. Technology is itself part of culture, part of a particular way of making sense, and is therefore not a value-neutral tool.[x] Therefore, it cannot be separated from culture, but it can be separated from nature, since early technology was inspired by nature, but the technical leap forward into modernity was inspired by nature. However, both technology and economy have a specific problem: they are cultural products, but they do not recognise national boundaries.[xi] This is how Freyer’s fear that the combination of capitalism and modern technology would create a “secondary system” that would threaten cultural particularities, and thus nations, emerges. Yet it was capitalism, not technology, that the Leipzig professor identified as the “culprit” behind the loss of meaning.[xii] The solution he proposed was the reintegration of technology into culture, which he called for through politics. In short, he wanted to make technology the lifeblood of European culture once again and prevent its alienation.[xiii]

Freyer’s Relevance Today

Freyer’s work became difficult to accept after the Second World War, but he still had significant academic recognition in Germany and the USA. In America, he had a major influence on Talcott Parsons, Edward Shils, Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann, notably with his book The Theory of Objective Mind.[xiv] In Germany, he played a major role in the development and evolution of social history. Hans Freyer’s importance in the continuum of German historiography lies in the fact that he conveyed concepts for the structural analysis of modern society that dated back to the 19th century and which had played a prominent role in German social science before 1914. These concepts grew out of concerns about the transformative effects of capitalism and technology, and what the Germans called “orienting science” (Orientierungswissenschaft), which would provide a secular and empirical vision of the direction of history and the place of contemporaries in that historical process.[xv] Freyer posited historical structures as products of political activity, emphasised the presence of multiple historical layers at any given moment, and stressed that concepts must be interpreted in terms of accumulated structures. He thus had a major influence not only on German structural history but also on the history of concepts that derived from it in the work of Otto Brunner, Werner Conze, and, above all, Reinhart Koselleck, whose theories on the temporal layers of history and on concepts reworked Freyer’s starting points. It was Freyer who developed the politically-oriented theory of history behind Koselleck’s Begriffsgeschichte. Freyer further posited the transition to industrial society in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as a historical break or “epochal threshold”, which bears a close resemblance to Koselleck’s saddle-time thesis (Sattelzeit). Freyer’s theory of history sheds light on the interrelationship between several key Koselleckian ideas, including temporal layers, the simultaneity of non-simultaneity, the predictability of history and the Sattelzeit.[xvi]

To conclude, it is no overstatement to claim that Hans Freyer is an undeservedly forgotten author whose ideas are still very relevant in the world of politics and sociology. Paying tribute to his work contributes to the preservation of the (radical) conservative tradition in European thought, especially in the discipline of sociology.

[i] Jerry Z. Muller, The Other God that Failed: Hans Freyer and the Deradicalization of German Conservatism, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1988, pp. 25-58.

[ii] Bé Cornelis van Houten, Tussen Aanpassing en Kritick, Deventer, Van Loghum Slaterus, 1970, p. 77.

[iii] René König, ‘Germany,’ in Joseph S. Roucek (ed.), Contemporary Sociology, New York, Greenwood Press, 1969, p. 789.

[iv] Max Weber, ‘A társadalomtudományos és társadalompolitikai megismerés “objektivitása”,’ in Tanulmányok, Budapest, Osiris, 1998, p. 29.

[v] Muller, p. 93.

[vi] Hans Freyer, Theory of Objective Mind: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Culture, Athens, Ohio University Press,1999, p. 79. (N.B.: This is the only book by Freyer translated into English.)

[vii] Hans Freyer, Soziologie als Wirklichkeitswissenschaft, Leipzig, B.G. Teubner, 1930, p. 81.

[viii] Ferdinand Tönnies, Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft – Grundbegriffe der Reinen Soziologie, London, Forgotten Books, 2018.

[ix] Muller, pp. 100-107.

[x] Muller, p. 104.; Felkai Gábor, A német szociológia története a századfordulótól 1933-ig II., Budapest, Századvég, 2007, p. 435.

[xi] Muller, p. 105.

[xii] Muller, p. 106.

[xiii] Felkai, p. 436.

[xiv] John H. Simpson, ‘Theory of Objective Mind: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Culture,’ in Sociology of Religion, 61/2, 2000, p. 240.

[xv] Jerry Z. Muller, “Historical Social Science” and Political Myth: Hans Freyer (1887-1969) and the Genealogy of Social History in West Germany, in Hartmut Lehmann and James Van Horn Melton (eds.), Paths of Continuity, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2007, p. 199.

[xvi] Timo Pankakoski, ‘From historical structures to temporal layers: Hans Freyer and conceptual history’, in History and Theory, 59/1, 2020, p. 62.