This is an excerpt from the keynote speech Father Mario gave at the conference “Christians in Pluralistic Society: Joseph Ratzinger 95” on Friday, 27 May at the National University of Public Service.

Natural law or the law of nature as defined by Black’s Law Dictionary is a ‘philosophical system of legal and moral principles purportedly deriving from a universalised conception of human nature of divine justice rather than from legislative or judicial action.’[1]

It is this that Jospeh Ratzinger who then became Benedict XVI reminds us in his numerous speeches, homilies, and writings on natural law. Yet his teachings are not just a mere philosophical or spiritual reflection. They are an appeal to the individual to ponder on God’s unwritten law inscribed in his or her heart so that he or she may better contribute to the common good of society.

The concept of a (natural) law based on man’s rationality Ratzinger talks about can be traced back to Heraclitus of Ephesus (c. 536 – 470 BC). He taught that there was an eternal and harmonious, as well as immutable norm based on a fundamental law, i.e., a divine logos, which for him was the principle order of knowledge.

St. Thomas Aquinas would develop the notion in his Summa Theologiae by saying the term natural in natural law refers to the idea that ‘every person is a participant in the rule and measure of things,’ i.e., eternal law, which is the Supreme reason that governs the world and is unchangeable.

Benedict XVI’s teaching on the law of nature has always been expressed in terms of its rapport between moral truths and the State, namely the formulation of positive norms. His purpose in promoting natural law in the body politic was to make evident the concept of safeguarding the dignity and individual natural freedoms of the human person created in the image of God, which is supposed to be the very foundation of democracy.

There exists ‘an objective and immutable truth, the origin of which is in God’

He made this clear during his General Audience of 16 December 2009, when he stressed there exists ‘an objective and immutable truth, the origin of which is in God, a truth accessible to human reason and which concerns practical and social activities. This is a natural law from which human legislation, and political and religious authorities, must draw inspiration in order to promote the common good.’

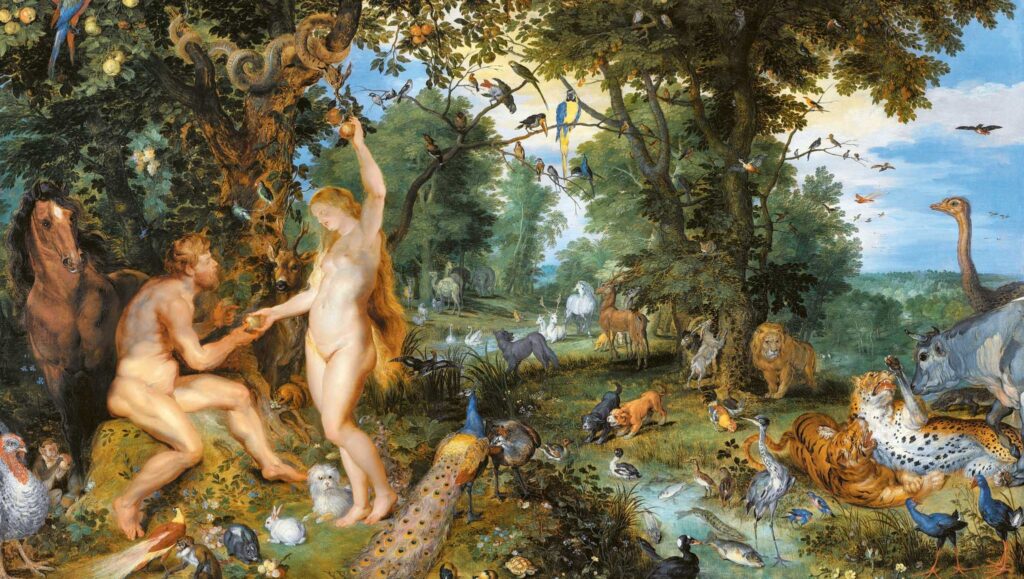

God, in His divine plan, created us with the capacity to naturally discern how to act, whether we are aware of His Commandments or not, as can be seen in the Genesis story of Cain and Abel.

After Cain murdered his brother, the Lord said to Cain, ‘Where is your brother Abel?’ Cain replied, ‘I don’t know…. Am I my brother’s keeper?’ (Gen 4, 9)

The context of this passage indicates that Cain, like Adam and Eve after committing the original sin, hid himself from God since he knew he had violated His precept, even though God had not yet given the Decalogue to Moses—the Commandment “Thou shall not kill” had not yet been given to man. Cain naturally knew the truth, though he did not want to embrace it.

The discernment of truth, or rather any claim to know the truth, is ‘[that] there must be law that derives from the nature, from the very being, of man himself,’ [2] not in the sense that man is the creator of his own moral tenets, but that they are innate to his human nature.

Perhaps the best understanding of Benedict’s teaching of the natural law can be seen in his 2007 address to the participants of the International Congress on Natural Moral Law :

‘The capacity to see the laws of material being makes us incapable of seeing the ethical message contained in being, a message that tradition calls (lex naturalis) natural moral law…. From it flow the other more particular principles that regulate ethical justice on the rights and duties of everyone. So does the principle of respect for human life from its conception to its natural end, because this good of life is not man’s property, but the free gift of God. Besides this is the duty to seek the truth as the necessary presupposition of every authentic personal maturation. Another fundamental application of the subject is freedom. Human freedom is always a freedom shared with others. It is clear that the harmony of freedom can be found only in what is common to all: the truth of the human being, the fundamental message of being itself, exactly the lex naturalis [natural moral law].’

Human freedom is always a freedom shared with others

There are two points in Benedict’s remarks that capture our attention immediately. First, the Pontiff’s use of the term lexand not jus. While both terms are parallel, they are nevertheless distinct:

- Jus (law, right), stems from the root verb iungere, to join; it is law in the abstract that refers to a right rather than a statute. It denotes an entire body of principles, rules—established and authoritative standards—and statutes, whether written or unwritten, by which the public and the private rights, the duties and the obligations of men, as members of a community, are defined, inculcated, protected, and enforced.

- Lex (law) is statutory law or positive law. It refers to rules or norms enforced by a head of state or legislature and are binding for its citizens and those within the confines of a State. Of course, it is understood that those who promulgate laws are invested to do so by the people under their jurisdiction or those who are found within it.

Jus was the preferred term for church jurists right through the Middle Ages so as to separate it from the arbitrariness of human law. According to the medieval historian Kenneth Pennington, Benedict separated and obfuscates the two traditions of jus naturale and lex naturale when he mentions that particular principles flow from the law of nature (lex naturalis).

This does not disqualify Ratzinger’s teaching on natural law, especially since in continental Europe jus and lex are synonymous, just as diritto and legge are in Italy. The argument here is not necessarily one of juristic semantics.

Medieval and early modern jurists understood jus naturale as a set of precepts, rights, and duties that were engulfed in jus

Pennington holds that ‘modern thinkers [not just Benedict] have embraced positivistic sets of rules, prohibitions, and norms, shaped, and fashioned according to each of their belief systems, that are and always have been the defining feature of lex.’ By contrast, medieval and early modern jurists, instead, understood jus naturale as a set of precepts, rights, and duties that were engulfed in jus. Benedict, I believe, was merely following the juridical concept of St. Thomas Aquinas who opts for lex naturalis.

The second point to be noted in Benedict’s aforementioned address is that he does not just say natural law” but uses the phrase “moral natural law.” It expresses what lies at the heart of his intention: to promote the concept in the political world.

Natural law expresses the fact that nature itself conveys a moral message. The spiritual content of creation is not merely mathematical and mechanical. That is the dimension which natural science emphasises in the laws of nature. But there is more spiritual content, more “laws of nature” in creation. It bears within itself an inner order and even shows it to us.

Advocates of natural law hold that it is an entity of norms which offers the power of analysis and guards against positions made in the discourse of moral argumentation, politics, and law. To quote a modern Islamic scholar, Ali Ezzati: ‘Natural law is natural because it is a system that challenges the systems which are not natural to man, such as positivism and scepticism.’[3]

For the Pontiff-Emeritus, natural law is not a law in force. Rather, it is a moral lex (or jus) that demonstrates that which is under the ethical-juridical aspect that can legitimately be a law in force. Accordingly, the juridical character of positive law, under an ethical component, depends on its agreement with natural law, which has been well-developed in the history of Western jurisprudence. Otherwise, as it happened in Germany under the National Socialists, the State turns into an instrument of destroying law (jus) and becomes itself the law.

[1] Bryan A. Garner, ed., Black’s Law Dictionary (9th ed.). St. Paul, West Publishing Company, 2009, p. 1127.

[2] Joseph Ratzinger, Europe: Today and Tomorrow, San Francisco, Ignatius Press, 2007, p. 74.

[3] Ali Ezzati, Islam and Natural Law, London, Saqi Books, 2002, pp. 12-13.