What approach should Christians take to modern politics? What are their obligations in contemporary public life? Which Christian values should be endorsed in modern democracy and which political instruments are permitted while doing so? Several Christian philosophers, theologians, and politicians have in the past sought to provide answers to these crucial questions. Our series of articles intends to rekindle interest in those authors, firstly because we believe that these authors receive less attention than they deserve, and without forgetting the extensive academic literature on them (since most of them attract serious scholarly interest) we argue that their ideas are underrepresented in public discourse. Secondly, we believe that to answer the questions raised above, one should be able to study acknowledged theologians and philosophers who are well-versed in the wisdom of the Christian faith and base their political arguments on it. Consequently, the political insights of modern theologians will be presented with a special focus on the Christian origins and sources of their ideas. We hope that these articles will increase public interest in these inspiring figures.

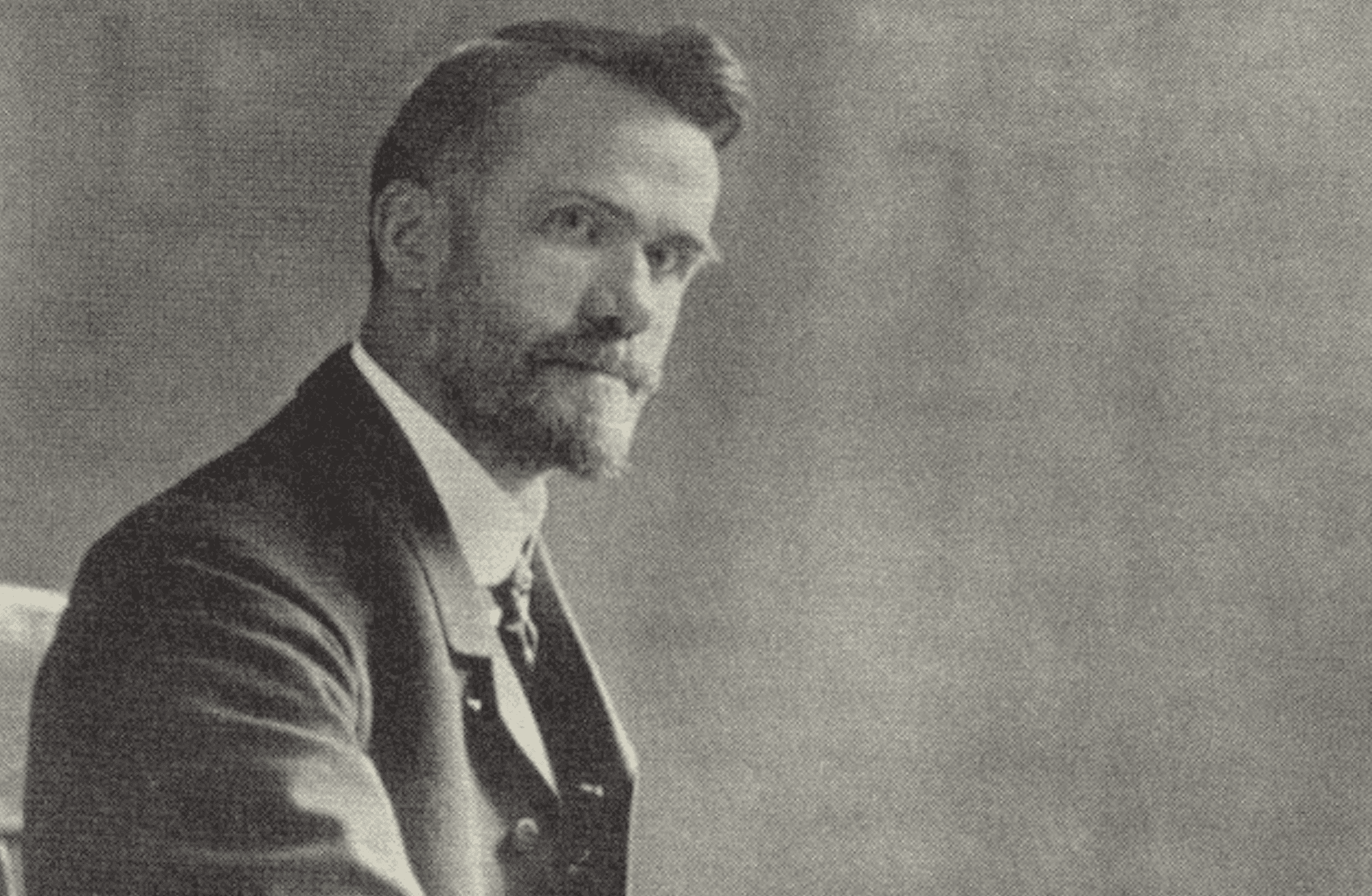

Our article series have already elaborated on several Catholic and Protestant Christian authors, including Abraham Kuyper, Reinhold Niebuhr, Joseph Ratzinger, Johann Baptist Metz, Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde, and Helmut Richard Niebuhr. In this piece, we venture to America again to immerse in the thoughts of Walter Rauschenbusch (1861–1918).

Like the aforementioned theologians, Rauschenbusch could also be connected to several waves of Christian thought. Broadly, he was—of course—a Christian thinker, but also a proponent of Social Christianity and the Social Gospel Movement. Although some authors refer to it as the ‘The Long Social Gospel’ (exceeding it until the Civil Rights Movement), generally, it is treated as a religious social movement prominent from about 1870 to 1920 in the United States. As the Encyclopedia Britannica writes, its advocates ’interpreted the kingdom of God as requiring social as well as individual salvation and sought the betterment of industrialised society through the application of the biblical principles of charity and justice.’[i] Several Christian laymen and women contributed to the issue of the Social Gospel, just like Protestant ministers who were undeniably among its leaders. Beyond the Congregationalist clerics, such as Washington Gladden, Josiah Strong, and Lyman Abbott, the Baptist pastor, Rauschenbusch was a decisive, if not the most influential figure of the movement.

Several reasons could provide an explanation for Rauschenbusch’s impact and significance. Considering the individual factors, his pastoral sense of mission, magnetic personality, and trained mind, first as a student, then as a professor of Rochester Theological Seminary, could be highlighted. But what made him famous and influential was the publication of his well-known books Christianity and the Social Crisis (1907) and A Theology for the Social Gospel (1917). Even though Rauschenbusch’s Christian social programme is clear from these writings and other significant books like The Social Principles of Jesus and the Christianizing the Social Order, we would apply another approach instead. Namely, we try to provide answers to the same question based on the collections of his prayers, entitled For God and the People: Prayers of the Social Awakening (1912).[ii] Our investigation will consider three aspects: first, we present Rauschenbusch’s intention with the book. Second, we will provide his interpretation of the Lord’s prayer. Third—wishing to find the social perspective of Rauschenbusch’s Christianity—we will take a closer look at those parts of the book which are related to social and political questions.

This new social situation requires Social Christianity, which makes a new type of Christian man who—hopefully, as far as he/she can— resembles Jesus

Why would someone write a new prayer’s book? Out of the several possibilities, Rauschenbusch’s explanation is the following: a new era of Christianity has arrived, the new mission, namely, the social purpose, gives new meanings to old Christian teachings, even to ones that are in the Bible. This new social situation requires Social Christianity, which makes a new type of Christian man[iii] who—hopefully, as far as he/she can— resembles Jesus. So there is a new feeling connected to a novel historical situation and, as he expresses, ‘these religious emotions ought to find conscious and social expression. The ordinary church hymnal rarely contains more than two or three hymns in which the triumphant chords of the social hope are struck. Our liturgies and devotional manuals offer very little that is fit to enrich and purify the social thoughts and feelings’.[iv] Living in a modern age cannot lack references to modern problems and their solution, not even in the case of prayers. Rauschesbusch perceived that ‘there is a great craving for a religious expression of the social feeling’.[v] Also, a prayer, which contains moral demands, might positively impact specific social actions. This collection of prayers serves as a step towards this new path.

But before writing new prayers, Rauschenbusch chooses another way of giving new religious inspiration by reinterpreting a prayer. Rauschenbusch’s central argument is that the Lord’s prayer—‘the purest expression of the mind of Jesus’[vi]—is an excellent heritage of Social Christianity. It is highly sorrowful that this crucial prayer has not been understood well (the personal meaning outweighed the social one), though it is not ecclesiastical, it has been used in ecclesiastical rituals, and its constant repetition has led to contrivance. He also argues that Jesus’s first words in the prayer, namely, ‘Our Father’, already points to oneness, the union of all human beings having the same father and the ambition to turn toward him. Yet, the most crucial part for Raushenbusch, and probably for the whole Social Gospel Movement, is embodied in the following position: ‘Thy Kingdom come. Thy will be done, as in heaven, so on earth’. [vii] Formerly Christianity wished to reach individual salvation with a pilgrimage on earth without facilitating a perfect life (moreover, they commonly treated it as a place of suffering). However, they were wrong; the reign of God must be brought to earth, as it is present in the prayer; God’s Kingdom should be duplicated. As Rauschenbusch writes: ‘the desire for the Kingdom of God precedes and outranks everything else in religion, and forms the tacit presupposition of all our wishes for ourselves’.[viii] Although later the baptist pastor tries to unfold the social dimension of the personal motifs in the Lord’s Prayer (such as the material part of asking for daily bread and the spiritual part of asking for forgiveness), the central thesis remains in the fact that he focuses and gives a new meaning to the idea of God’s Kingdom in the prayer.

The rest of the book consists of around fifty prayers on different topics. Although there are “traditional” prayers (e.g. morning prayer, night prayer) with new additional aspects (the social dimensions are more highlighted), the most visible sign, which signifies that the reader holds an unusual collection, appears in the fact that most of the prayers are for social groups and classes: the coerced, the children, who work and are on the street, the women, who toil, workingmen, and immigrants. These prayers represent deep solidarity and social sensitivity from Rauschenbusch. He asks God to relieve their pain and provide material and spiritual well-being for them. He also hopes that working organisations will be places of concord and mutual support. Before suggesting that Rauschenbusch was biased towards the lower classes, two important notes must be made. First, he explicitly condemns class pride, which he views as a ‘deadly poison’.[ix] Second, he is also very attentive towards the higher classes, such as employers, businessmen, public officers, judges, and even the kings and the magnates. Though he does not forget to ask God to help avoid specific sins (such as oppression, corruption, misuse of power), he acknowledges that they are leaders of the nations, the welfare of the societies depends on them. In this sense, while he is socially devoted, his views, at least in these two aspects, are in contrast with communists and most socialist thinkers.

It should also be noted that Rauschenbusch is exceptionally modern in various instances. First, showing his romantic self, he prays for the lovers (naturally limiting the possibilities of love to those situations, which are in accordance with God’s commandments). Second, in more cases, he writes about the defence of Creation; for instance, once he beautifully underlines the shared responsibility in keeping the world as it is,[x] then writes a separate prayer ‘for those who come after us’.[xi] Third, already in 1907, he prays for women asking for good balancing between work and motherhood.[xii]

First, he treats the sense of duty essential in political life. Beyond the fact that he explicitly asks for it, he underlines the unique responsibilities of certain groups in public life

Considering the form of state, Rauschenbusch votes for democracy while condemning tyranny.[xiii] Although it could not be stated that—through prayers—he developes anything close to a political theory, his political convictions are solid and clear in several aspects. First, he treats the sense of duty essential in political life. Beyond the fact that he explicitly asks for it,[xiv] he underlines the unique responsibilities of certain groups in public life: public officers should govern the nation following the common good, lawyers and legislators should follow the eternal order and justice, journalists should write the truth in newspapers, judges should interpret human law unbiased (in counsel with the Holy Spirit). Second, in different parts of the book, Rauschenbusch—by asking for them in prayers—acknowledges the importance of specific values in politics, such as order, stability, freedom, rights of the people, cooperation and patriotism. Third, the pastor held that men in history, since Abel, ceaselessly continued the war against each other. Naturally—ormulating a pacifist position—he asks God to end wars to live in times of peace.[xv] Still, the most crucial notion, which dominates Rauschenbusch’s and his proponent’s idea and fosters social and political action, is that everyone, in the bonds of brotherhood and sisterhood, should work to realise the Kingdom of God on earth. Just think about it, even if it is seen utopian, how powerful this idea is if one takes it seriously.

[i] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, ‘Social Gospel’, Encyclopedia Britannica, 10 Oct. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/event/Social-Gospel, accessed 27 January 2022.

[ii] Walter Rauschenbusch, For God and the People: Prayers of the Social Awakening (Boston, New York, Chicago: The Pilgrim Press, 1910).

[iii] Naturally, Rauschenbusch, just like his contemporaries used man as an inclusive term, meaning all human beings.

[iv] Rauschenbusch, For God and the People: Prayers of the Social Awakening, 10.

[v] Rauschenbusch, For God and the People: Prayers of the Social Awakening, 11.

[vi] Rauschenbusch, For God and the People: Prayers of the Social Awakening, 15.

[vii] Rauschenbusch, For God and the People: Prayers of the Social Awakening, 16.

[viii] Rauschenbusch, For God and the People: Prayers of the Social Awakening, 19.

[ix] Rauschenbusch, For God and the People: Prayers of the Social Awakening, 34.

[x] ‘When our use of this world is over and we make room for others, may we not leave anything ravished by our greed or spoiler by our ignorance, but may we hand on our common heritage fairer and sweeter through our use of it, undiminished in fertility and joy, that so our bodies may return in peace to great mother who nourished them and our spirits may round the circle of a perfect life in thee.’ Rauschenbusch, For God and the People: Prayers of the Social Awakening, 48.

[xi] Rauschenbusch, For God and the People: Prayers of the Social Awakening, 109–110.

[xii] Rauschenbusch, For God and the People: Prayers of the Social Awakening, 55.

[xiii] Rauschenbusch, For God and the People: Prayers of the Social Awakening, 75.

[xiv] Rauschenbusch, For God and the People: Prayers of the Social Awakening, 75.

[xv] Rauschenbusch, For God and the People: Prayers of the Social Awakening, 97.