This article was originally published in Vol. 4 No. 3 of our print edition.

Hungarian intellectual history tells us that there have so far been two Budapest schools. One comprises those belonging to the circle of disciples surrounding György Lukács and his ideas—especially Ágnes Heller and Ferenc Fehér, and also (with the appropriate caveats) György Márkus, István Hermann, and Mihály Vajda. These thinkers initially believed in a renaissance of Marxism based on its original teachings. As Vajda writes: ‘I could say that we inherited our belief from Lukács, who argued that we had to return from the dogmatism of official Marxist–Leninist philosophy, which distorts original Marxist philosophy, to authentic Marxism. This faith comprised the common platform.’ Afterwards, however, Vajda adds that ‘I turned back to philosophy [and] in the meantime I “realized” that I was no longer a Marxist, by which I probably meant that I was opposed to philosophy becoming an ideology’.1

This personal turn is an important warning of the danger lurking in any branch of modern philosophy, namely that philosophy can become an ideology, meaning that it can be transformed into a kind of secular means of salvation.2 In stating this, we do not of course ignore other problems of philosophy that exist under modern conditions, such as the tension between the modern sciences and philosophical knowledge, the outcome of the skewed relationship between the secular and the sacred, the relationship of man as a social being to himself as an individual, and to other people (the body politic). Of course, Vajda’s perspective is just one among those in Lukács’s circle, but he expresses the essence of the problem well: there was a hugely influential thinker, Lukács, who impressed the young people around him, who were anxiously waiting to see if Lukács’s great work, the uncompleted Ontology of Social Being, would establish a materialist foundation for ethics, but the effort was unsuccessful (as it has remained in philosophy ever since) and Lukács’s disciples themselves criticized the work.

Although the question of which of Lukács’s acolytes truly attained the status of ‘philosopher’ is disputed, the fact that, ideologically, Lukács’s disciples continued to dominate Hungarian philosophical life far beyond his death is less so—as proven, for example, by the work of Sándor Radnóti, who, at a political-ideological level, still dominates the academic part of Hungarian philosophical life to this day. There is equally little doubt that the so-called ‘Budapest School’ or ‘Lukács Circle’ became internationally renowned, and philosophical lexicons continue to mention the Budapest School as an element in the history of philosophy.

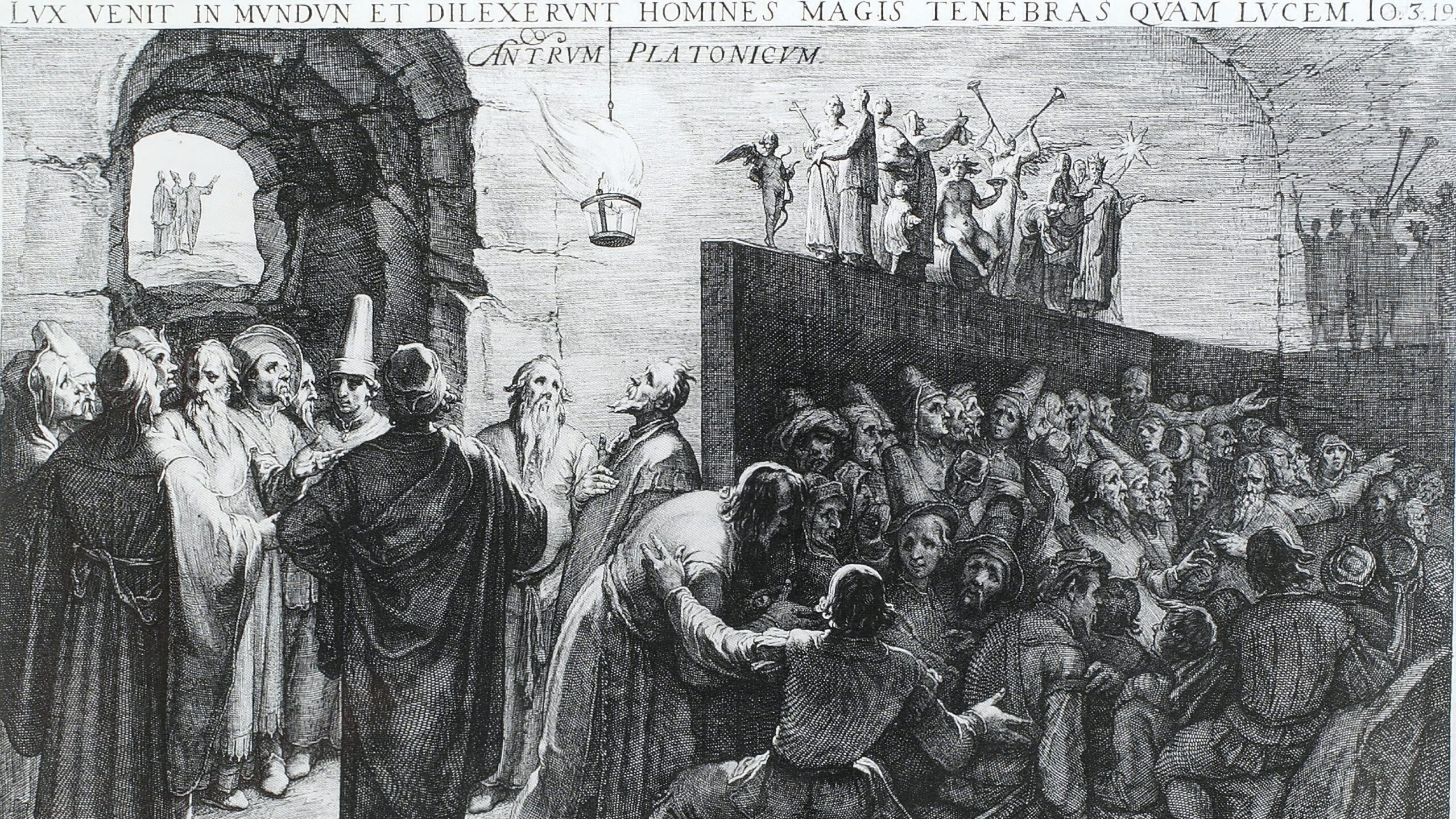

By contrast, the other or, in my opinion, Second Budapest School is the Budapest Dialogic School, though its best-known representatives, Béla Tábor and Lajos Szabó, are still almost unknown even to audiences grounded in philosophy. There is nothing surprising about this, since in modern times, only philosophy that has a definite political edge, direction, or ideological aspiration arouses any interest. Modern politics could not exist without philosophy, since it is now conceived of in terms of the nominalist approach, so it is very easy to multiply the number of ideological statements since nominalists have the least concern for the truth. The revival of Plato or Platonist philosophy is always synonymous with the resurrection of realism: words are not just words, but real entities that have a direct impact on human life. It was the friendship of the two thinkers—Tábor and Szabó—that formed the basis for the school, which operated illegally for fifty years or so. It is hard to say where a ‘school’ begins and a mere association of friends ends. Whichever point we choose as marking the time when Tábor and Szabó’s friendship could be called a school, it was clear from the beginning that, after the expunging of Marxism, the consistent representation of the primacy of the spirit comprised an intellectual force representing something completely different from that proposed by Lukács and his circle, or any other intellectual grouping espousing Marxist ideology.

We read of this group that ‘the Budapest Dialogic School believes in the primacy of the spirit and, within this, the primacy of the word. It perceives both rationalism and irrationalism as products of the decay of a unified spirit. It considers rationalism too narrow a framework for meaningful research into the real problems of the spirit. The Latin word ratio covers only one section of the field of meaning of the Greek word logos. What is excluded is that which was translated into Latin as verbum: living speech, the personal word. Logos, which includes both verbum and ratio, is the space for the search for truth. Truth is not an object, but a personal, dialogic relationship. In this sense, the Budapest Dialogic School rephrases the eternal basic questions in the linguistic and ideological environment of the logocentric, demythologizing zeitgeist.’3 In a variety of ways, many thinkers were connected to this circle, including Béla Hamvas, Lajos Fülep, and others. What is even more important is that classical philosophical thinking continued even when communist ideology, the core of which is Marxist philosophy, exercised complete political domination over all public intellectual outlets.

The Classical Foundations

The foundations of Hungarian culture are Latin in nature, thus indirectly including ancient Greek elements. The importance of this can be understood by assessing the practical use of the two dead languages—ancient Greek and Latin—and even more so their indirect educational power. For the Hungarian language and nation to exist to this day, it is necessary that the classical roots of the Hungarian language should remain alive (the classical era of Hungarian linguistic reform was itself an attempt to respond to the influences of foreign languages at the time), and that deformations resulting from—primarily English-language—influences should be resisted. If no Hungarian philosophical and scientific language exists, then nor can political sovereignty.

‘The Third Budapest School strives to debate the one-sided, analytical, progressive, nihilistic aspirations that dominate American intellectual life’

When we evaluate Hungarian intellectual achievements, we chiefly focus on those that have garnered international acclaim, especially in the form of the Nobel Prize. It should be noted, on the one hand, that it is common to refer to the so-called ‘Martians’, i.e. the Hungarian physicists and mathematicians so termed by Leó Szilárd, including János Neumann, Ede Teller, Jenő Wigner, and of course Szilárd himself. Those scientists who published discoveries and inventions that expanded the frontiers of human intelligence, and the practical, material consequences of their discoveries, had a profound impact on the history and aspirations of humankind. At the same time, it would be both unfair and misleading to overlook the achievements of another, very significant Hungarian intellectual school, not coincidentally connected to the Reformed school on Lónyay Street, where the twentieth-century Hungarian classical philology or classical studies school took shape.

The preeminent Hungarian scholar of antiquity is Károly Kerényi, who was prevented by Lukács from returning to Hungary from Switzerland because, according to Lukács, in him a representative of fascism would return… As an ideologue, Lukács repeatedly abused his status as philosopher when it came to promoting communist political matters. Kerényi lived in Switzerland from 1943, working for four years as a visiting professor of Hungarian language and literature at the University of Basel. In the summer of 1948, Lukács published an article about Kerényi in Társadalmi Szemle (Social Review), representing him as a servant of fascism who refused to return to his homeland. Kerényi was an internationally recognized scholar of ancient history and religious studies. One way or another, Hungarian classical studies starts from Kerényi, and his most renowned disciple is the art historian János György Szilágyi, who gave a full biographical interview at the beginning of the 2000s.4 From this, it becomes clear that the greatest Hungarian practitioners of classical philology, and indeed of classical studies as a whole, were all educated in one place, the Lónyay Street school. Gyula Muraközy, Gábor Devecseri, Zsigmond Ritoók, and others all helped ensure that the classical roots of Hungarian culture continue to bring forth fresh growth to this day. This intellectual circle played a huge role in providing Hungarian translations and interpretations of most classical works. What is more, even our natural scientists attained excellence thanks to their classical education, mediated by Hungarian scholars of antiquity.

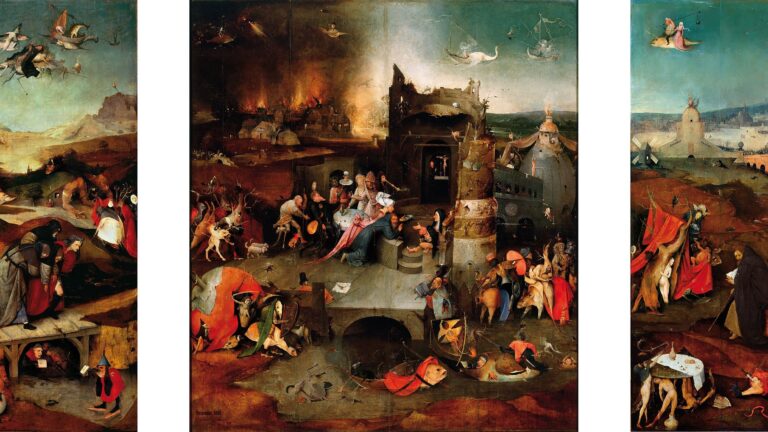

Without the classics, there is only vacuous modernity, with all its attendant ills: reason without faith, unlimited worship of everything new instead of reality, absolutization of the part rather than the whole, destructive nihilism that drowns out questions of the meaning of life in irony and cynicism, the totalization of salvation through politics. There is a historical parallel: the era of decay and decline of the ancient Greek spirit known as the Hellenistic Age. We witness such decay when reason becomes uncertain in its assessment of the human condition, a phenomenon of which there were countless signs even in the Hellenistic Age. This was the period when for the first time caricature, which of course can be called a humorous or grotesque view of life, flourished; genre boundaries became blurred in the visual arts; ‘there was a crisis in the sense of monumentality’,5 i.e. the admiration for majesty and greatness arising from the size of works of art was relativized by changing the sizes of statues at will; it became fashionable in portrait art for Roman clients to model their own heads on classical Greek figures, indicating a strengthening of egoism; and the baroque development observed in Hellenistic art brought with it increased focus on external appearance, representation, and superficiality. When the meaning of human life fades, the direct relationship between human action and human goals is broken. The Third Budapest School, building on the classical understanding of political knowledge, is unimaginable without understanding the activities and results of the intellectual trends encapsulated by the Second Budapest School.

The Place of Political Philosophy

There is a domain of knowledge that can hardly be understood in Hungarian, and that is ‘political philosophy’. The concept is used in many places and languages around the world, but its precise boundaries are not fixed, and its interpretation depends greatly on the experiences and intellectual connections of the given academic and political community. However, regardless of what exactly we consider political philosophy to be, there is a widely agreed starting point, and that is the period known as the ancient Greek Enlightenment, which also witnessed the birth of medicine (Hippocrates) and the so-called ‘Socratic turn’, which interrogated the social nature of humanity.

The questions of the pre-Socratics were directed towards the cosmos, the universe as a whole, and not to the nature of man as a social being (microcosm). Socrates was the first to direct his attention from the macrocosm to man, the microcosm, saying that if we do not understand who we are and why we have the opinions we have, we have no hope of correctly interpreting the cosmos either. The essence of the Socratic turn is that we make opinion the starting point for all our cognitive efforts. ‘Opinion’ here refers to public opinion, the set of ideas formed by people living in a community, in possession of speech, and forms the foundational knowledge without which we cannot ask questions that seek knowledge beyond opinion. Such questions are inherently political because we are social beings, and all questions and opinions affect all members of the community, whether they like it or not. The so-called Socratic turn is perhaps the greatest, and certainly the first, revolutionary intellectual change in the history of European thought.

Traditionalism, i.e. unquestioningly following of the usual path, either through a kind of thoughtless irrationality or—especially later—on the basis of faith, was, from this point on, no longer self-evident. The primary characteristic of European culture is an awareness of the possible conflict between the individual and the community—and at times a willingness to exploit that conflict. In the world of human coexistence, the question is always whether the existing system is supported by the citizenry, and whether there is enough space for the expression of individual ideas. Philosophers—including Socrates—undertook to interrogate then-existing opinion, developing the goals and choosing the tools and methods of philosophy. Today, many see the Socratic turn as the birth of political thought, theory, or philosophy. The term we choose to employ is by no means incidental since ‘thinking’ encompasses much more, including the results of everyday opinion formation and the speeches of politicians, but also the academic works of theorists. In contrast, political philosophy studies politics from an explicitly philosophical perspective.

Political philosophy is, first of all, a branch of philosophy, and indeed its most practical branch. Its aim is to examine in more depth the most comprehensive questions that arise during human social coexistence. This means that it does not seek to intervene in day-to-day political battles, but that it does attempt to name the problems and difficulties that are inherently political. It wishes to elucidate more comprehensively the emerging political ideas, concepts, and political goals that influence the decisions of a given community. Political philosophy entails an attempt to get from political opinion to political knowledge. This effort can be seen in the Platonic dialogues, which usually—though not always—feature Socrates as their central protagonist. Whatever issue is at stake—justice in the state, say—he always asks his interlocutors for their opinions. After they have given their opinions at length, Socrates begins to speak in the language of rationality, attempting to refute their opinions and discover the answer that best approaches the truth. If there were no truth to be had, all speech would be useless; if life had no meaning, then the distinction between good and evil would have no meaning either, and a nihilistic mindset would prevail—as has indeed happened in modern European culture.

What Socrates conducts is an active search for the truth: philosophy is dialogic, and the never-ending process of searching for truth can be deepened through conversation between people. The minute we write something down, the danger of introducing dogma, and thus an arbitrary departure from reality, immediately arises. Consolidating an idea in written words takes you one step further from action. Politics, on the other hand, is primarily action, i.e. the execution of actions; therefore, the philosophizing of politics is a mistake, preventing the formation of apt policies. What is more, it can even lead to the breakdown of norms, and ultimately chaos. This was Edmund Burke’s fundamental problem with the French Revolution. Philosophical politics is, after all, the way of modernity, but this is not the purpose of political philosophy; it is, instead, for asking the most important questions that relate to the meaning of human life, because only while searching for answers can individuals break out of their individual misery and live a good life as social beings. This requires political knowledge. That is the essence of Aristotle’s understanding of politics: since the ultimate questions of human life all boil down to ‘how to live’, the most comprehensive knowledge will be political knowledge: the episteme of politics. In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle claims that politics is the ‘master science’, upon which the goals of all other sciences depend.6 Throughout the Hungarian version, political knowledge is translated as ‘state science’ or ‘the art of state administration’. The ultimate goal is to raise awareness of the pursuit of good, and to think about the best form of government, but not for someone to ‘introduce’ it.

In modernity, i.e. the age of the idealization of the ‘new’, there develops the form of political thought that we call ideology, the purpose of which is the self-realization of the individual mind (see also the intellectual consequences of the Enlightenment) and an impatience to put its insights into practice. Today, we are surrounded by conceptual jargon: political philosophy, political thinking, political theory, ideology. In today’s political struggle, these terms are largely synonymous. However, the reason why political philosophy is not an ideology was expressed with impressive simplicity by Blaise Pascal: ‘We can only think of Plato and Aristotle in grand academic robes. They were honest men, like others, laughing with their friends, and, when they diverted themselves with writing their Laws and the Politics, they did it as an amusement. That part of their life was the least philosophic and the least serious; the most philosophic was to live simply and quietly. If they wrote on politics, it was as if laying down rules for a lunatic asylum; and if they presented the appearance of speaking of a great matter, it was because they knew that the madmen, to whom they spoke, thought they were kings and emperors. They entered into their principles in order to make their madness as little harmful as possible.’7

So let us conclude that philosophy necessarily includes politics, but politics does not necessarily include philosophy. Elevating politics to the level of philosophy was—and remains —the utopian plan of the modern Enlightenment, regardless of whether we receive the promise of Marx’s salvation on earth in a historicist guise, or the welfare state in the form of a fair society achieved through liberal-scientific analysis. However, it transpires, all politics in modernity come with the tacit promise of earthly redemption. This cannot be altered so long as we judge the human condition according to the standards of modernity.

The greatest task of political philosophy today is not simply the fight against utopias that circumscribe reality, but to fight against nihilism using the tools of classical—i.e. pre-modern rational—thinking, so that the meaning of human life can again become self-evident. For classical and pre-modern authors, nihilism did not even arise as a maladaptive, destructive feeling and thought that makes human life impossible even during our earthly existence. Human life is a unique possibility in the history of existence, which probably cannot be the work of chance, but even if it were, we can derive more hope if we consider the entire universe and the law-based nature within it to be intrinsically meaningful.

The Americanization of Political Knowledge

A political system can be successful over the long term in the modern world only if it enjoys sufficient philosophical and intellectual support. This is because the modern state, based on modern contract theory, has eliminated both divine law and classical thought related to natural law, as well as the reference base of modern natural law. According to the classical view, one must adapt to the laws of nature, whereas according to the modern view, nature must be overcome. According to the classical view, the world is governed by natural justice, whereas according to the modern interpretation, it is governed according to agreement. Natural justice is ultimately of divine origin and certainly has transcendent roots, while the only guarantee of modern government through agreement is that people, by agreeing, create and establish institutions in writing (a written constitution) that are able to counterbalance the sins and bad intentions that arise from human imperfection. This view is supported by American culture and politics.

The United States was originally a state apart and sought to isolate itself from the world. However, after the Second World War, the American elite finally came to the conclusion that they would have to either shape the world in their own image or else find themselves in a chaotic world. The United States became aware of its own economic and political power and shaped its impact on the world accordingly. It exerted economic or military influence, depending on which seemed most efficacious, but always and everywhere spread the superiority of its intellectual and cultural life and lifestyle, primarily through films, with a profound impact on our lifestyles. The products of American culture sought to convince the world that the American experiment is the best human condition and way of life that had ever been created. And not without success, because a significant part of the world became Americanized, including even those that otherwise were—and in some cases still are—America’s political opponents or enemies. Why has the programme of Americanizing the world been so successful? Not because of its current material power, nor the present American ideology of democracy, but rather on account of the political wisdom that attended its founding. The United States is attractive to many because of the jurisprudence and institutions formed on the basis of constitutionalism and practices combining classical natural law and republican ideals—not because of the way it has tried to manage global affairs since the end of the Second World War.

If we raise the question from the perspective of political knowledge, then it is also important to interpret the development of American academia. The founding of the United States owes a great deal to classical political knowledge: ancient philosophy and the teachings of Christianity and the Bible influenced the figures who drafted the American Constitution, who also used John Locke’s theory of the social contract. American constitutionalism has been able to survive for so long because it combines elements of classical, early modern, and modern political knowledge. So long as it remained on this foundation, the United States was a beacon of hope and could sustain itself. Later, however, it drifted away from its own intellectual principles, having been diverted by nineteenth-century intellectual influences from Europe.

The influence of German social sciences had a decisive impact, from the last few decades of the nineteenth century until the arrival of the Frankfurt School in the United States. There are those who claim that the German progressive philosophical and social science approach has altogether subjugated American universities.8 Humboldt’s concept of a university penetrated both the natural and social sciences. In the former, the representatives of the German natural sciences promised that nature could be conquered, while in the social sciences progressivism was promised. Accordingly, the elements of classical literacy based on a knowledge of ancient Greek and Latin, in line with the political worldview of the American founders, gradually faded into the background. From then on, however, American academics went to Germany to learn the progressive social science approach.

In his book, through case studies of Columbia and Johns Hopkins universities, Jeffrey E. Paul shows how the progressive mindset of German social science penetrated American universities. According to him, ‘at Columbia, John William Burgess established the School of Political Science, the nation’s first doctoral program in political science, history, and economics. He received his doctorate at Berlin. He studied under German professors like Theodor Mommsen and Heinrich von Treitschke, both of whom rejected natural rights philosophy for a view that society generated rights and who argued for an evolutionary understanding of moral principles. Among the first students at Columbia was Edwin Robert Anderson (PhD at Columbia 1885), who would be the architect of the Sixteenth Amendment, which established the national income tax.’9

The same thing happened at Johns Hopkins: ‘Here three faculty members, including Richard T. Ely, helped disseminate German philosophy throughout the country and eventually into government. Hopkins trained John Dewey, and Woodrow Wilson, and those who eventually brought progressivism to the University of Wisconsin and to Robert LaFollette’s Wisconsin. Ely went to Madison to establish a new School of Economics, Political Science, and History and he brought his students John R. Commons and Edward Alsworth Ross with him. Soon they were helping to staff the government. One-sixth of Wisconsin faculty served on government commissions. One devotee wrote, just as World War I was to break out: “Wisconsin is doing for America what Germany is doing for the world.”’10 The German academic influence meant that American intellectual life gave up the original principle of natural justice (natural law) in a political sense, replacing it with the principles of progressive governance. It is interesting how directly this change of thinking led to the transformation of the American tax system—the principle of ‘no taxation without representation’ was replaced by the concept of ‘taxation without limits’, which was meant to cover the ever-increasing government tasks and spending.

American academic life was infected with Marxism through members of the Frankfurt School who fled to the United States. Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno emigrated to the United States in the mid-1930s and then returned to Germany, but people belonging to the school, such as Herbert Marcuse, turned the (cultural) Marxist sentiments of the Frankfurters into a political force. The New Left rebellion of the 1960s was decisive in establishing Marxism within American academic life. This was embodied in the concepts of historical progress, oppression, counterculture, ‘make love, not war’, and a host of other expressions that linguistically aligned the majority of American intellectual life with the neo-Marxist conception of society. This marked the United States’ ultimate break with European classical thinking and at the same time with its own founding principles.

In recent decades, American progressive philosophy and social science have tried to bring European academic circles under their influence, and have had some success. Currently, the progressive viewpoint dominates the majority of Western universities. Indeed, this was true even before the latest egalitarian political movement, represented by LGBTQ rights and other similarly radical egalitarian movements, penetrated university and academic circles. Let us simplify the formula: according to progressive radicals, there are no truths independent of time and place, and truths are only valid in the here and now; as such, all arguments referring to the past or making use of the knowledge of the past are harmful and should be eradicated. Wisdom does not exist either as a form of knowledge or as a moral commitment; only utilitarian and political knowledge, i.e. ideology, possess a legitimate existence. This means that all understanding is relative, good is indistinguishable from evil, and human life has no meaning since it comes from nothing and moves towards nothing. For now, modernity has taken the side of nihilism, but this—like everything else—is not inevitable, except for political philosophies that have turned into ideologies. The task is for ideology to find its way back into the realm of political philosophy, where the question is more important than the answer.

The Third Budapest School

Vajda came to the realization that the ideological mindset represented by Lukács must be returned to philosophy. The other, or Second Budapest School, the Dialogic School, initially rejected the modern compulsion to become an ideology, but its influence was always very narrow. The Third Budapest School wishes to cultivate the original, classical meaning of political philosophy, which is why the European Centre of Political Philosophy was recently established with institutional support from Mathias Corvinus Collegium (MCC). It aspires to develop into a school because the ultimate goal of all thinking and research is to promote education. By ‘school’, we have in mind the original sense of the term: schole, i.e. the time spent in contemplation and understanding the entirety of existence. The goal is to learn about truth, goodness, and beauty. Whereas the currently dominant Euro-American culture wants to jettison its past in the service of particular political or ideological goals, the aim of the Third Budapest School is to restore the classical image of man, to reclaim political-philosophical thinking from the influence of progressive American academia, and to restore our culture, which has sunk into nihilism, to an understanding of the meaning of human life by asking important questions. The one who asks is the one who thinks.

Every intellectual initiative begins with a survey of what already exists. Since the beginning of modernity—in political thought since Machiavelli—there has been a debate about how to assess the content of European culture, i.e. whether the ancients or the moderns give better answers to the most fundamental questions confronting humankind. A good basis for understanding this debate is provided by Pascal, who stood on the brink of modernity and perhaps saw most clearly what was being lost and what it was being replaced with, as we can read in his Pensées (1670). What has been lost is a moral sense resulting from the limited nature of faith and human reason, and what takes its place is the self-belief and egoistic morality of modern rationalism, as well as the lurking nihilism of the modern age that Pascal glimpsed in his discovery of boredom.

Later, the literature of the decline of the West continued the debate between the ancients and the moderns. Kierkegaard interpreted modernity, Nietzsche identified it with nihilism, Schopenhauer used pessimism as the final interpretive framework, Spengler saw in civilization the ‘Twilight of the West’, Heidegger saw in it the fulfilment of technology, and Ortega y Gasset highlighted the morally corrupting effect of mass society so that the merciless criticism of modernity continued in the long-hidden escolios, or glosses, of the Colombian thinker Dávila. However one evaluates modernity, one thing is certain to have permanently changed the lives of Westerners in it: the loss of a sense of meaning in human life. In contrast to the people of all other cultures, Westerners live as though life comes from nothing and falls back into nothing. Even if this had an element that could be considered rationally, it makes the life of a living person appear to be a part of nothing, which takes place in complete moral nihilism. If we deprive people of the comfort of the other world, the possibility of redemption, then the living will become the undead.

Let us ask the question: what is natural truth? The whole of classical European philosophy until modern times accepted the concept of natural truth, meaning that truth cannot be relative. The guarantee of truth is guaranteed by laws external to humankind. Divine law and natural law imply powers that cannot be influenced by human will. Natural truth determines what is good and bad, there is no room for relativization. Modernity, however, in order to resolve the tension between the constant (truth) and the changing human experience, introduced the dynamic concept of history, which was called ‘historical progress’ in ideological language. Historical progress relativizes everything since only that which is new and displaces the past is considered good. Modernity directs attention from the past to a constantly reimagined future. However, this leaves the person living in the present in a state of complete uncertainty. Moreover, a person living in uncertainty is unpredictable, and the danger of war has certainly not decreased in modernity. It may even have increased with the perceived or real possession of technical superiority.

Let us continue by asking: why the classics? In the nineteenth century, Sainte-Beuve was one of the first to attempt to define what we mean by the ‘classics’. The Greeks considered their own canonical literature as ‘classic’, whereas the Romans looked to the Greeks. From then on, however, the question was always—though the Middle Ages were a bit confusing in this regard—which author possesses authority and admiration. Who can be counted on to suggest continuity and permanence, create unity, and pass on traditions? Who is harmonious in style, with rationality expressing itself in virtues, soul, talent, and taste? The classics themselves are wisdom shaped by time. Modernity placed knowledge above wisdom, whereas the classical perspective is the other way around, considering knowledge to be a part of wisdom. Knowledge is always directed to some part because it is empirical, whereas wisdom is directed at the whole because knowledge is not only understood in the scientific sense. The classics are the collection of the best authors and works according to a canon that has developed over time. As Thales said: ‘Time is the wisest of things, for it finds out everything.’11

But why should Europe be reclaimed from the United States? For a long time it appeared that the American experiment would, in effect, be a purified form of classical Europe. Until the First World War, the United States fed on the intellectual capital of classical Europe, thinking of itself as a classical republic. The law was understood on the basis of natural law, human rights were traced back to natural-law foundations, and the modern understanding of democracy hardly played a role in the interpretation of the American state. Then the modern positivist–utilitarian progressive conception gradually displaced natural law thinking. The republic became a modern democracy as soon as women received the right to vote (in 1920, through the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution) and through the consolidation of such superficial propositions as ‘every man may recognize his own self-interest’ and ‘democratic decision-making eliminates possible mistakes’. With the development entailed by the two world wars and the globalization potential of capitalism, the United States finally abandoned its policy of isolationism and set itself the goal of creating the ultimate objective of progressive thought, the world state. The world state would be identical to an American empire, run in terms of economic and technological supremacy, with the intellectual and academic world dominated by American political philosophy, the essence of which is to reconcile the abstract idea of equality with the norms of legal freedom.

John Rawls is seen as the founder of this process. The truth of this is exemplified by the entire structure and editorial principles of the Oxford Handbook of Political Theory, published in 2006, and its focus on John Rawls: ‘In the mid-twentieth century John Rawls single-handedly revived Anglo-American political philosophy, which had not seen significant progress since the development and elaboration of utilitarianism in the nineteenth century. Rawls reinvented the discipline by revising the social contract tradition of Locke, Rousseau, and Kant.’12 It is clear that the author of the study was not especially interested in processes taking place in philosophical life elsewhere: it is primarily what is happening in Anglo-American intellectual life that matters. What is classical cannot be progressive, so it does not matter that by the time Rawls even came on the scene, Leo Strauss had written the text of his Jerusalem lecture in 1954–55, finally published in 1959 under the title What Is Political Philosophy?13 Strauss was not alone in renewing political philosophy on a classical basis: Eric Voegelin and Hannah Arendt also emigrated to the United States and represented classical European political philosophy. The difference in approach between Anglo-American analytic philosophy and European or continental philosophy was soon contrasted. Classical political philosophy only visited the United States as a guest or forced emigre, which is why the time has come for classical political philosophy to return home to Europe. The reason for this is that classical political thinking has a chance to take deeper root in Europe than in America, and Europe is in great need of posing, without arrogance, the basic questions of politics.

The Third Budapest School strives to debate the one-sided, analytical, progressive, nihilistic aspirations that dominate American intellectual life, and to cultivate initiatives based on classical European philosophy. It does this by stimulating the formulation of important questions: in contrast to the activist Leninist ‘What is to be done?’, the Third Budapest School holds that the preeminent question is: ‘What is to be asked?’ This means that the most important measure of all intellectual activity is reality. However, in an age when truth and reality themselves have become questionable, what remains besides the proliferation of endless logical constructions, a profusion of data, or the mere expression of political will with little intellectual consideration. All democratic polities are threatened by two dangers. One is the rabble of mob politicking, and the other is the perpetuation of a state of leaderlessness. A gaping void, a hopeless lack of leadership, or bad leadership can cause the ultimate destruction of any political community. After all, this is ultimately the crux of the matter: every political thought must serve the good of the community in the name of truth. However, this is only possible through familiarity with a reality that it is all too easy to lose sight of.

In his autobiographical writing, Eric Voegelin argued that the main task of philosophy is to grasp reality: ‘The most important means of re-establishing our relationship with reality is to return to the thinkers of the past who did not lose sight of reality, or made an effort to regain it.’14 According to Voegelin, modernity has been flooded with ideological language to such an extent that ‘language has become so degraded and corrupted that it is no longer suitable for expressing the truth of existence.’15 The goal of the Third Budapest School is to rehabilitate reality in a philosophical, political, and artistic sense.

Translated by Thomas Sneddon

This article was originally published in Hungarian in the 2 (2024) issue of the journal Kommentár.

NOTES

1 Mihály Vajda, ‘Lukács és a Budapesti Iskola’ (Lukács and the Budapest School), 2000, 2 (2017).

2 For more, see: András Lánczi, ed., Politikai megváltás. Lehetséges-e racionális politika? (Political Redemption: Is a Rational Politics Possible?) (Közép- és Kelet-európai Történelem és Társadalom Kutatásáért Alapítvány), 2023.

3 László Surányi, and Ádám Tábor, ‘A Budapesti Dialogikus Iskola’ (The Budapest Dialogic School), https://lajosszabo.com/BPDISKMAGY.html, accessed 24 June 2024.

4 ‘Egzisztenciális tudomány – Interjú Szilágyi János Györggyel. I–II. rész’ (Existential Science—Interview with János György Szilágyi, Parts I and II), Enigma, 87–88 (2018).

5 János György Szilágyi, A hellenisztikus görög művészet (Hellenistic Greek Art) (Gondolat– Képzőművészeti Alap, 1959), 30.

6 Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics (Hackett Publishing, 2019), 1094b.

7 Blaise Pascal, Pensées (Penguin Books Limited, 2003), 331.

8 Jeffrey E. Paul, Winning America’s Second Civil War: Progressivism’s Authoritarian Threat, Where It Came from, and How to Defeat It (Encounter, 2024).

9 Jeffrey E. Paul quoted in Scott Yenor, ‘The German Invasion in Social Science’, Law and Liberty (24 February 2024), https://lawliberty.org/book-review/ the-german-invasion-in-social-science/.

10 Yenor, ‘The German Invasion in Social Science’.

11 Diogenes Laërtius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers (Oxford University Press, 2020), I/9, www.gutenberg. org/cache/epub/57342/pg57342-images.html#Page_23.

12 Richard J. Arneson, ‘Justice after Rawls’, in John S. Dryzek, Bonnie Honig, and Anne Phillips, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Political Theory (Oxford University Press, 2006), 45.

13 Leo Strauss, What Is Political Philosophy? (Free Press, 1959).

14 Eric Voegelin, Autobiographical Reflections (Louisiana State University Press, 1989), 93.

15 Voegelin, Autobiographical Reflections, 93.