This article was originally published in Vol. 4 No. 2 of our print edition under the title ‘Questioning “Progress” and Liberalism: Thomas Molnar’s Radical Critique of the “Liberal Hegemony”’.

Molnar’s Radical Critique of Modernity’s ‘Enlightenment’

In seeking to understand Hungarian-American Catholic philosopher Thomas Molnar’s (in Hungarian Tamás Molnár, 1921–2010) critique of liberalism, we should first approach it as a critique of broader historical processes and philosophical standpoints. We can say with little exaggeration that Molnar’s entire oeuvre is itself a radical critique of the Enlightenment and ensuing modernity. Above all, he questioned the idea of progress, the notion that, paraphrasing Leibniz’s Theodicy, the modern world is ‘the best of all possible worlds’. Without exception, he thoroughly criticized the ideological structures into which the political world has tried to integrate itself during the last two and a half centuries.

There can be no question that Thomas Molnar’s thought was often driven by a confrontation with the intensified secularist, materialist, and anti-religious ideological tendencies following the socio-historical and ideological period of the eighteenth century. He sought the roots of modern political philosophies such as liberalism and Marxism.

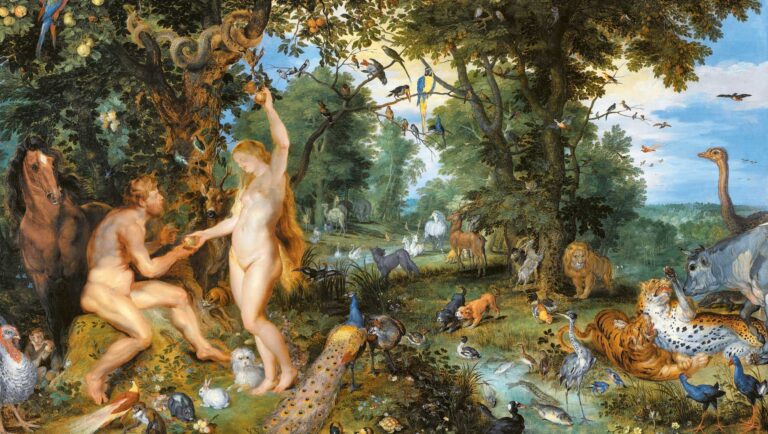

The anti-metaphysical, anti-theological, ‘anthropocentric’ worldview of modernity in which the meaning of life, human happiness, and all other fundamental values were limited to the merely material sphere of existence was in Molnar’s eyes extremely open to criticism. In his specific approach, he defended a worldview based on a pre-Enlightenment assertion of divine transcendence, transcending the material reality of both history and society, and coexistent with a non-hedonistic view of humankind which goes beyond mere material needs.

For Molnar, a decidedly Catholic thinker, modernity manifests itself primarily in the gradual loss of the aforementioned religious and/or theological view of existence, whether through the denial of the transcendent root of being by ideological materialism or in its simply fading from the human soul by processes not strictly ideological. This, however, means not just the complete secularization of politics and society but also the loss of the inner and subjective experience of transcendence as ‘completely different’ (Ganz Andere—in reference to Rudolf Bultmann) from human existence.

Molnar tried to defend the philosophical position—in clear opposition to the materialist/naturalist view of the world—that existence has a certain ontological structure defined by non-material principles and, in his view, any political theory and reality which opposes the fundamental world order cannot be ‘just’ or ‘true’. His criticisms of materialist thought and its approach to history, society, science, and human nature appear in his most significant socio-political works, such as Utopia: The Eternal Heresy and, from a somewhat different perspective, also in The Liberal Hegemony: The Rise of Civil Society, which is perhaps his best known work among his French and Hungarian readership. In The Liberal Hegemony, Molnar identifies liberalism with the ‘ideology of civil society’ and sharply criticizes its ideals.

Questioning ‘Progress’ and Liberalism

Perhaps the most interesting aspect (and merit) of The Liberal Hegemony is that its author is brave enough to question the ‘progressionist-evolutionist’ mindset and vision that takes historical progress and development for granted. The notion of history as ‘progress’ has been so prevalent in European social science since the nineteenth and even the eighteenth centuries that it has become almost impossible to question. Progress has been attributed first and foremost to the spread of the rationalist philosophy, which has left little room for metaphysical thought directing man’s ‘gaze to the earth’. Progress has been interpreted in terms of changes in humanity’s social and political life, such as the elimination of ‘serfdom’ the improvement of ‘human rights’, the abolition of monarchy and aristocracy, and more ‘civilization’: literacy, better hygiene, growing life expectancy for the individual, and the overall development of natural sciences. The idea of progress became so dominant from the mid-nineteenth century that quite a few academic historians and philosophers felt compelled to depict the fate of human culture as one of decline, or alternating periods of rise and fall, with such exemptions as Nietzsche, Toynbee, and Spengler—themselves largely outside or in the fringes of the academic world.

‘Liberalism’ a predominantly political term derived from the Latin liberalitas (generosity) was linked to the transition from a monarchic to a democratic age, and portrayed as a ‘natural’ and benevolent transition from an era of political oppression to an age of freedom. The doctrine of popular sovereignty is deemed to be connected with the notion of the ‘autonomous man’ espoused by liberalism: an individual who freely shapes his or her own destiny and does not depend on any external sovereignty, be it human or divine. Still, the term ‘liberalism’ has a certain connotation which can be associated with ‘greater liberty’—or at least greater liberty than humanity enjoyed in pre-Enlightenment periods of history. The term was also associated with democracy—although many prominent liberals were in reality staunch anti-democrats—and also, with ‘fairness’ and ‘justice’. In general, we can say that liberalism, according to its most widespread contemporary theorists and adherents, is a political philosophy based on the principles of liberty and equality, and as a system of political thought that fosters and strengthens democracy.

Molnar’s analysis of liberalism—although he does not analyse every kind of liberalism or every possible aspect of the nuances and connotations of the term—is coherent and logical throughout, while completely overturning the usual set of criteria outlined above. Thus, he completely reverses the so- called ‘progressive’ view of history. Molnar’s critique of ‘liberal hegemony’ is a story of decline rather than a universal success story.

According to his analysis, disguised within the narrative of liberty and freedom, what really matters is the loss of real, meaningful, existential freedom, with a fixation on the material spheres of existence and the rise of a civil society which can be associated with the greatest—but mostly ‘indirect’—regulations ever imposed on human life. He detects increasingly mechanical processes in all spheres and levels of existence, an effort at homogenization, the most significant symbol of which is the machine. As he states in his essay, Soul and Machine, the machine, the symbol of the industrial age, is a tool of utopia because the machine offers an answer to everything—it is enough to articulate the need and a mechanical solution can be found—just as in the age of faith, when one prayed and was heard.1

Molnar’s Critique of the Liberal Hegemony

One of Thomas Molnar’s most important political works, The Liberal Hegemony identifies three key social actors: church, state, and civil society are all natural forms of human coexistence. In his view, these three forms coexist everywhere, in every social form, from tribes to empires. They also strive to overcome each other because they share a common desire to exercise control over the whole of society. However, since none of them has had the strength to do so, they have remained in a kind of equilibrium. This fundamentally changes with the onset of modernity. The state decides, implements, and organizes; the church exercises spiritual and moral authority; and civil society represents ‘constant movement’, its activities encompassing everything that is strictly outside the state and the church, such as agriculture, commerce, industry, banking, and education. The relationship between these three institutions determines the fundamental cohesion of any given political order. In modernity, according to Molnar, we can talk about the hegemony of one of these actors. Civil society arrogates to itself a hegemonic role, and this situation ‘has been prepared by the thinking minds of civil society…well in advance’.2

According to Molnar’s analysis, prior to modernity, the—admittedly often conflicted—coexistence of state and church often dominated political life, and this duality determined social processes. Civil society was at best a marginal player. Molnar suggests that in the pre-Enlightenment Christian world, there is a kind of transcendent orientation permeating society, implying that the existence of the human community was directed towards a non-material state of being. The task of the state, in addition to organizing the political and economic life of society, was to create the conditions necessary for salvation after death. It was the heyday of the medieval idea of the ‘Christian Empire’ or Res Publica Christiana. This idea also ensures the integrity of society, and Molnar argues that without an idea pointing toward transcendence, society will inevitably become fragmented, as human existence cannot find its purpose merely in itself. However, with the disintegration of the traditional orders of society, civil society is gradually pushing its rivals into the background, and political relations are rearranging themselves. The political thinking of Machiavelli, Bodin, and Hobbes already reflects this fundamental shift. This is the period wherein philosophical individualism, atomism, and materialism emerge, conceptions radically at odds with the transcendent image of the human person and existence, which were prevalent before modernity.

‘What really matters is the loss of real, meaningful, existential freedom, with a fixation on the material spheres of existence and the rise of a civil society’

During the eighteenth century, Molnar argues, a further escalation of this process can be discovered in the philosophies of Mandeville, Locke, Kant, and Montesquieu. By this time, the earlier principle of reference—namely that society should be focused on transcendence—is completely pushed into the background. References to God slowly disappear from social life and political thinking is thoroughly secularized. The next phase begins in the nineteenth century and lasts roughly until the 1950s. Molnar claims that subjects living in modern capitalism unconsciously imitate the behaviour of their machines. It is not the individual who has become more moral or civilized, but rather the standard of morality that has fallen. That is the sole reason we can say that ‘public life is increasingly permeated by morality’.3 Morality appears to take the place of politics. However, this appearance is deceptive, and civil society alone is incapable of creating a genuine morality; it must always use something outside of itself to do so. Thus, instead of morality, civil society creates a mediocre sentimentality that is nothing more than pseudo-altruism, a simulacrum of morality, while focusing on a single goal: the gigantic enterprise of materialistic production, consumption, and economic growth.4

The ideology of civil society that has gained hegemony in modernity can be summarized under the heading of ‘liberalism’. This ideology positions itself as the engine of change and at its root embodies a ‘profane, secular, anti-sacral’ worldview and mentality. In Molnar’s view, the clash of liberalism with state and church was a conflict between worldviews, as the activities of civil society, unlike the other two fundamental institutions, the state and the church, are purely material: ‘The activities of civil society are hardly ritualizable and not surrounded by mystery at all.’5 Liberal ideology negates the centrality of both state and church, because for the liberal, power is something harmful in and of itself. In Molnar’s analysis, liberalism seeks to divide power between units with little influence in themselves: society fragments into various churches, groups, lobbies, and arbitrary or spontaneous agglomerations.

The main goal of the liberal media is to control and manipulate the masses—in this regard, it is similar to war propaganda—providing spectacle and life advice, to produce a ‘civil religion’, while at the same time, unlike the medieval church, eliminating the transcendent. Television (and now, the internet) makes the world ‘transparent’, but the essence of the new sacred is precisely the lack of sacredness, pure phenomenality, stripped down to nothing.6

‘It is not the individual who has become more moral or civilized, but rather the standard of morality that has fallen’

Liberalism fundamentally approves of human desires tied to material interests, while the virtues, which are the foundation of the church and state, are not recognized by it at all.7 Civil society always fought against the state and the church with the help of pressure groups, or ‘lobbies’, living in symbiosis with parliament. Parties in liberal systems are essentially no more than the ‘peaks of plutocratic-oligarchy interests’, and the parliament, which is ‘oligarchy in democracy’, relies on the views of lobby groups while legitimizing itself through the people.8

The market is nothing more than ‘the model example of a rationalist conception’9 since the market is based on a kind of consensus, completely in line with the roots of liberal epistemology: this social mechanism is not about who is right or wrong, but about achieving the economically correct price in an amoral fashion. The most likely verdict will thus be what everyone accepts, so liberal society will trace all human endeavours to exchange between interchangeable blocks of values. The fatal shortcoming of liberal ideology is that it does not recognize the essential sacredness of collective references. Being a proponent of a completely horizontal organization, liberalism is insensitive to human experiences of verticality and vertical connectivity. Interpreted in theological terms, liberalism is the pseudo-sacralization of things, since desacralization always points in the direction of the sacralization of false idols, and in the course of history, ‘we can speak for the first time of an immanentist society seeking its own references’.10

Molnar, however, sees that neither state nor church is a structure that could utterly be destroyed, as ‘the state begins where the individual ends’. As Saint Thomas Aquinas also emphasized, the individual is primary and the state is secondary, but without the integrative power of the state, individuals would be unable to live or thrive. If rights are given only to the individual, the disintegration of society will begin: ‘man will be the wolf of man’ (Hobbes).

In one of Molnar’s other significant works of political philosophy, Two Faces of Power: Politics and Holiness, he argues that in essence, underlying all premodern social and state arrangements, we find the sacred. This conception has never been separable from political power in the course of human history, and also marked the purpose of state power. This is to represent a transcendent reality beyond this world yet within this world. Molnar’s detailed analysis of the interplay of political power and religion suggests that the sacralization of political power in pre-Enlightenment eras represented a kind of permanence for premodern man: something that prevented society from submerging into purely profane activity.

According to Molnar, prior to modernity, we may posit the existence of a community—or at least a certain orientation within human communities—that pursued goals beyond material interests, as opposed to the society of ‘liberal hegemony’, in which everything becomes a commodity and of which the highest point of reference is the market.

Evaluation of Molnar’s Analysis of Liberalism

As Molnar puts it in the opening lines of The Political Principles of Modernity, ‘We are talking about modernity, but we put a lot of emphasis on thinkers who are described as reactionary or at least “antimoderns” and [who] have formulated an “opposite”, or a “different” kind of political philosophy’.11 This ‘different kind of political philosophy’—in his view at least, is intellectually valid.

Being himself one of such ‘reactionary’, Molnar did not fear to question the ideological absolutes which tend to be seen as inviolable, unshakable, and unbreakable by the majority of political philosophers and the masses alike. His critique of the liberal worldview can be traced back to his critique of philosophical and practical materialism. Materialism, which is not just characteristic of liberal-capitalist societies, but of socialist-communist collectivism as well, entails the denial of a worldview of (sacral) significance beyond the mere material wellbeing of the individual, while naive faith in progress is also prevalent. This seems to be the main characteristic of all the political theories and realities of modernity with which Molnar very strongly disagrees.

Molnar makes us reflect. This is certainly due to the realization on the part of the sufficiently sensitive observer that there has been a break somewhere in the historical process, a change of forces that represents a radical change, something that he perhaps portrayed in the most elaborate form in Moi, Symmaque (I, Symmachus). The essence of such a processes is perceived by the ‘Symmachuses’. Symmachus is one of the last pagans among the Roman senators, who is living during the transition from pagan antiquity to the Christian Middle Ages, and whose side is somewhat surprisingly taken by Molnar, a decidedly Catholic thinker. He undoubtedly formulates a critique of his age, but as Molnar emphasizes, there is a fundamental difference between the modernity that is current for Symmachus and ours. While the ancient world no doubt replaced its gods, the ontological status of the world ‘remained the same’, whereas ‘We didn’t replace the furniture; we demolished the house.’12

NOTES

1 Tamás Molnár [Thomas Molnar], Én, Symmachus/ Lélek és gép (Moi, Symmaque / L’âme et la machine) (Európa, 2000), 138.

2 Tamás Molnár, A liberális hegemónia (The Liberal Hegemony) (Gondolat, 1993), 12.

3 Molnár, A liberális hegemónia, 12.

4 Molnár, A liberális hegemónia, 94–106.

5 Molnár, A liberális hegemónia, 18.

6 Molnár, A liberális hegemónia, 63.

7 Molnár, A liberális hegemónia, 19.

8 Molnár, A liberális hegemónia, 26.

9 Molnár, A liberális hegemónia, 39.

10 Molnár, A liberális hegemónia, 44.

11 Tamás Molnár, A modernség politikai elvei (The Political Principles of Modernity) (Európa, 1998), 5.

12 Molnár, Én, Symmachus/Lélek és gép, 18.

Related articles: