This article was published in Vol. 3 No. 1 of the print edition.

America Is Living in an Era of Abundant Energy Options

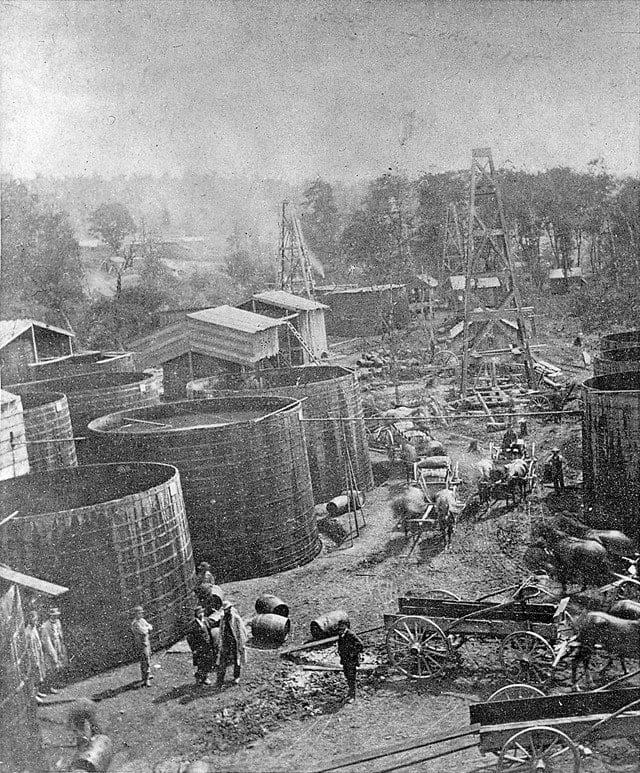

America is a vast, resource-rich land and global leader in innovation technology. In less than 250 years since our founding in 1776, the United States has experienced eras of energy abundance, energy independence, energy dependence, and even energy dominance. We have seen the highs of the oil boom in the early 1900s,1 the lows of energy embargos in the 1970s,2 and the unlocking of centuries worth of oil and gas with the shale gas revolution starting in the early 2000s.3

In the earliest days, like most developing countries, we were dependent on wood as our one and only source of energy. By the 1880s, the US was powering its way through the industrial revolution with coal. From the 1900s to the 1930s, oil was booming in places like Oklahoma, enabling cars to soon become ubiquitous.4 After the Second World War, nuclear energy began to develop and from 1960 to the 1990s grew to become a significant source of electricity.5 Solar and wind energy along with hybrid and electric vehicles started to take off in the early 2000s. At that same time, the shale gas revolution began to take shape and America went from being a net energy importer to a net energy exporter. Today, US energy sources are more diversified and abundant than ever before.

That said, it is ironic that the policy of successive US administrations has left the energy sector more exposed and less efficient, with consequent geopolitical risk, than if it had pursued a more prudent geo-energy politics. Energy policy is certainly strategically and politically salient. American gas prices at the pump hit an all-time high in the summer of 2022, electricity prices soared in parts of the US, and states like California and Texas experienced blackouts and grid failures from record-breaking heat and historic winter storms.6 But that feels somewhat self-indulgent and parochial, given that in Hungary and across Europe, citizens face a winter with energy rationing as Putin’s war rages on in Ukraine.

Bad Climate Policy Is Worse Than Bad Climate Change

Bad climate policy, as we daily witness across Europe, is a threat to geopolitical order. Or, put another way, bad climate policy is potentially worse than bad climate change. To be clear, I am not saying that climate change is not a risk—it is. And I am not saying that all climate policy is bad, it is not. But not all policy is created equal, and policies that deny free markets to function by dictating winners and losers based on political goals unhinged from reality are politically dangerous and potentially catastrophic.

Look no further than Germany and the overzealous climate policies that defy common sense. In the name of saving the planet, Germany’s green climate energy policies have put its people and the planet in serious peril. Germany’s politicians shut down their coal and nuclear power plants, doubled down on solar and wind, and turned to Russian gas for baseload and backup electricity generation. As a result, Putin was emboldened to invade Ukraine, cut natural gas supplies to Germany, and now all of Europe is experiencing an energy crisis with few options but to turn its coal power plants back on, and ration energy leading into a worrisome winter.7

The US is by no means perfect either. At its best, America’s energy policy is free market oriented and encourages energy abundance, competition, consumer affordability and energy security. At its worst—and all too frequently since the Reagan era—America’s energy policy is over reactionary, politically myopic, short-sighted and even schizophrenic.

President Biden’s Energy Policy to End Fossil Fuels Is Fundamentally Flawed

In a few short years, we have gone from a president who promoted an energy policy based on ‘all of the above … energy dominance’, to a president that sees climate change as an ‘existential threat’, like an asteroid hurtling for the earth for which we should pull out all of the stops with his ‘all of government’ and ‘everything but’ approaches that together with ‘Medicare for All’ will save the planet.

In America, President Biden has declared he will ‘end fossil fuels’.8 To back it up, he immediately cancelled the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline from Canada to the US, threw out reforms to the federal permitting process that would have greatly accelerated all types of energy projects, stopped drilling and new permitting on US federal lands, asked OPEC to increase production while at the same time depleting the Strategic Petroleum Reserve in an effort to reduce gasoline prices just months before an election, and in November 2022, gave Chevron permission to produce and export oil from Venezuela.9

Let us review and expand briefly on the issues just mentioned. On the Keystone XL pipeline, even Obama administration economist Larry Summers recently said that ‘It’s kind of insane that we have trucks and trains carrying oil all over this country, rather than constructing pipelines, which would permit accessing more resources and cheaper, safer transmission’.10 If you care about reducing greenhouse gas emissions, pipelines are far better than filling the roads with diesel trucks and trains.

Meanwhile, on permitting reform, the reforms that Biden threw out—ironically—would have accelerated energy projects of all types in the US, including solar, wind, pipelines, small modular advanced nuclear, and LNG terminals, to name the most obvious. But because they would have also accelerated permitting for oil and gas, and were devised by the Trump administration, they were completely abandoned.

Similarly, stopping drilling for oil and gas on federal lands both on and offshore looks less than coherent. At the same time President Biden could be seen begging OPEC to produce more oil, he was preventing the production of oil and gas in the US and depleting our Strategic Petroleum Reserves during a global energy crisis: all to lower gas prices at the pump just weeks before mid-term elections.11 Adding insult to injury, the recent decision in November 2022 to allow a major oil company to produce and export energy from Venezuela, a country known to be corrupt and led by a ruthless dictator, seems geo-strategically inept at best, at worst a dereliction of the national interest. Not exactly a prudent American energy policy.12

To be fair, President Biden’s agenda has also been proactive in terms of dedicated taxpayer dollars and energy innovation by pushing for and signing into law a record breaking $400 billion spending bill touted by many environmentalists as the most important climate bill in history, the so-called Inflation Reduction Act.13 And while there is a lot to not like about it from a free market perspective, at least it takes a broad, almost-all-of-the-above approach that includes funding across the board for research, development, and deployment for not just solar, wind, biofuels, and electric vehicles, but also for grid resiliency, small modular nuclear, energy storage, hydrogen, and carbon capture sequestration and utilization.

President Biden also signed another $280 billion into law with the CHIPS bill, which subsidizes American-made semiconductor manufacturing and spends more money on scientific research. Together, these laws make up the most aggressive industrial policy that America has experienced in the last 50 years or more.14

The Perpetual Pendulum of Presidential Energy Policies

Historically, America has seen Presidents and their energy policies come and go. In the 1970s, President Nixon signed one of the most sweeping environmental protection laws into place, called the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA. For more than fifty years, NEPA has served a purpose of protecting the environment. In that same time, it has also slowed down clean energy projects, added hundreds of billions of dollars to clean nuclear energy projects, and ironically been a spoke in the wheel for addressing climate change.15 Subsequently, President Jimmy Carter mandated gas rationing, created the US Department of Energy, and invested in alternative fuels in response to the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries’ (OAPEC) oil embargo, and put solar panels on the roof of the White House.16

President Reagan, by contrast, removed price caps, lifted regulations to allow the free markets to work, created the Synfuels Corporation in a failed attempt to develop advanced synthetic fuels, and removed the solar panels from the White House.17 President George H. W. Bush led the fight and rallied support from the United Nations to fight and quickly win Desert Storm in Kuwait, defending freedom, democracy, and access to oil. President Clinton, unforgettably and perhaps unforgivably, gave America its first ‘Climate Czar’ in Al Gore, who made millions with his doom-and-gloom movie An Inconvenient Truth.18

‘Follow those price swings and you will find a trail of American energy policies’

Repeating what was becoming something of a pattern, President George W. Bush declared an end to America’s addiction to foreign oil, signed the first major and all-encompassing energy bill in over ten years into law, pursued a ‘hydrogen economy’, and signed the Energy Innovation and Security Act which significantly increased America’s R&D and grid security budgets and accelerated the growth of intellectual property in the US.19 By contrast, President Obama threw record amounts of money at renewable energy ‘shovel ready’ projects when he signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) economic stimulus bill into law,20 stood up the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E),21 and signed the Paris Agreement.

Somewhat predictably, President Trump cancelled US participation in the Paris Agreement, imposed tariffs on Chinese solar panels, opened up drilling in the United States, passed a sweeping tax reform bill that had an unreported positive impact on energy efficiency and clean energy, and pushed ahead on offshore drilling, the Keystone XL pipeline, permitting reform, and virtually anything that bolstered his ‘energy dominance’ agenda.

All of these policy pendulum swings were responses to real or perceived geopolitical threats in one form of another. And all of them were made in the context of one of the biggest movers of American energy policy—the price of oil.

Energy Policy Is Still Driven by Oil Prices

Consider the price of oil over the last fifty years.

- At the start of the 1970s, oil was about $2.75 per barrel.

- By the start of the 1980s, oil had reached $25 per barrel.

- By 1999, oil had dropped back down to only $8 per barrel.

- One year later, in 2000, oil was all the way up to $30 per barrel.

- After 9/11, oil dropped to half of what it had been a year earlier to $15 per barrel.

- In 2003, it was $30/barrel; in 2004, it was $40/barrel; and in 2005, it was $50/barrel.

- By 2007, it was $99/barrel.

- In 2008, it reached an all-time high of $147 per barrel, and by the end of that same year, oil had dropped to $36/barrel.

Follow those price swings and you will find a trail of American energy policies.22

All of this reminds me of a saying in Oklahoma: ‘If you don’t like the weather, just wait a minute.’ Although energy policy changes on a time scale of decades, not minutes, the reality is that if you do not like America’s energy policy, just wait a year, or two, or ten.

The Foundations of American Energy Policy Are Not So Easily Moved

While presidents and the price of oil clearly have set the tone for American energy policy, it is important to know that America’s energy policy is not monolithic and cannot change overnight. Rather, it is made up of a patchwork of policies and policy makers that start at the local city, county, and state levels, and rise to regional and federal levels. The United States has 19,495 cities, 3,143 counties, and 50 states, all having a say in energy policy. And do not forget Congress. Congress has more committees that have a say on energy policy than any other issue. So, while the policies of presidents can come and go relatively quickly, the policies of Congress ebb and flow and can take decades to change.

Durable Energy Policy Is Balanced Energy Policy

Fundamentally, the best and most durable energy policy is one that recognizes that energy security, economic competitiveness, and environmental stewardship are inextricably linked. People and economies need access to abundant energy to flourish, and that energy must enable us to be good stewards of the environment in which we live.

One could say the same about good climate policy. It must recognize that if we are to minimize our impact on the climate and environment, we must have access not just to clean energy, but also abundant and affordable energy. Without energy security and economic competitiveness, responding to the changing climates will be a luxury left to the elite. This leads to the final and most important point about US energy policy.

The Best Energy and Climate Policy Is Economic Freedom

Economic freedom is the solution to all of these problems. Defined by how much people are free to control their own destiny and property, choose where they work, what they produce, consume, and invest, in economically free societies the proper role of governments is to allow labour capital, and goods to move freely, and refrain from coercion or constraint of liberty beyond the extent necessary to protect and maintain freedom itself.

‘The best way to address environmental challenges like climate change is to expand economic freedom around the world’

As C3 Solutions demonstrates in its annual Free Economies Are Clean Economies report that compares decades of data from the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom and Yale’s Environmental Performance Index, countries that are economically free are twice as clean as countries that are economically unfree.23

Clearly, the best way to address environmental challenges like climate change is to expand economic freedom around the world. This is especially true in the developing world. Developing countries will need increasing amounts of energy as they develop. They will also need increasing amounts of economic freedom to be democratically sustainable. These countries demand and deserve to grow economically. At the same time, they demand and deserve a better climate and environment, both of which economic freedom can deliver.

Ultimately, if you care about climate change, economic freedom is the answer. If you care about energy security, economic freedom is the answer. If you care about your country’s economic competitiveness, economic freedom is the answer. Fundamentally, the best energy policy for geopolitical order, moreover, for a flourishing people and planet, is one that embraces and expands economic freedom.

This article is based on a talk delivered at the ‘Second Summit on Geopolitics, Security and Defence’, organized by the Danube Institute, Budapest, on 1 December 2022.

NOTES

1 Jennifer Latson, ‘How the American Oil Industry Got Started’, Time Magazine (June 2019), https://time.com/4008544/american-oil-well-history/, accessed 9 January 2023.

2 ‘The Oil Shocks of the 1970s’, Yale Teaching Units (Yale University Press, 2023), https://energyhistory.yale.edu/units/oil-shocks-1970s, accessed 9 January 2023.

3 Ed Crooks, ‘The US Shale Revolution’, Financial Times (24 April 2015), www.ft.com/content/2ded7416-e930-11e4-a71a-00144feab7de, accessed 9 January 2023.

4 Gib Knight, ‘A Look back at One of the Biggest Oil and Gas Fields’, Oklahoma Minerals (November 2016), www.oklahomaminerals.com/look-back-one-biggest-oil-gas-fields, accessed 9 January 2023.

5 Stephanie Hinnersnitz, ‘The Atomic Energy Act 1946’, The National World War II Museum, Washington (August 2021), www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/atomic-energy-act-1946, accessed 9 January 2023.

6 ‘Texas Storms, California Heatwaves and Vulnerable Utilities’, The New York Times (18 February 2022), www.nytimes.com/2021/02/18/business/energy-environment/california-texas-blackouts-utilities.html, accessed 9 January 2023.

7 Javier Blas, ‘The Worst of Europe’s Energy Crisis Isn’t over’, The Australian Financial Review (5 December 2022), www.afr.com/companies/energy/the-worst-of-europe-s-energy-crisis-isn-t-over-20221205-p5c3vr, accessed 9 January 2023.

8 Joe Biden, ‘I guarantee you we’re going to end fossil fuels’, Washington, October 2022, YouTube, www.youtube.com/watch?v=OJ7MMsheHzQ, accessed 9 January 2023.

9 David Blackman, ‘Why Biden’s Killing of Keystone XL Was a Big Energy Blunder’, Forbes Magazine (May 2022), www.forbes.com/sites/davidblackmon/2022/03/10/why-bidens-killing-of-keystone-xl-was-a-big-energy-blunder/?sh=2f15779313fd, accessed 9 January 2023.

10 ‘Obama Administration Economist Calls Biden’s Energy Policy Kind of Insane’, Power the Future (November 2022), https://powerthefuture.com/obama-administration-economist-calls-biden-energy-policy-kind-of-insane/, accessed 9 January 2023.

11 Juliana Kaplan, ‘Biden Just Took a Big Swing at Lowering Gas Prices’, Insider (October 2022), www.businessinsider.com/biden-trying-to-lower-gas-prices-ahead-of-midterm-elections-2022-10, accessed 9 January 2023.

12 Marianna Parrage, ‘US Prepared to Authorize Chevron to Boost Venezuela’s Oil Output’, Reuters (November 2022), https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-prepared-authorize-chevron-boost-venezuelas-oil-output-2022-11-23/, accessed 9 January 2023.

13 The White House, How Inflation Reduction Act Will Help Small Businesses, Washington, September 2022, www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/09/12/fact-sheet-how-the-inflation-reduction-act-will-help-small-businesses/, accessed 9 January 2023.

14 The White House, Chips and Science Will Lower Costs Create Jobs Strengthen Supply Chains and Counter China, Washington, August 2022, www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/09/fact-sheet-chips-and-science-act-will-lower-costs-create-jobs-strengthen-supply-chains-and-counter-china/, accessed 9 January 2023.

15 The White House, Chips and Science, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/nixon-sign-nepa.

16 Emma Pattie, ‘The White House 1972 Climate Memo That Should Have Changed the World’, The Guardian (June 2002), www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/jun/14/1977-us-presidential-memo-predicted-climate-change, accessed 9 January 2023.

17 Harvey Amster Priddy, ‘United States Synthetic Fuels Corporation Its Rise and Fall’, Texas Scholar Works (June 2013), 1–25, https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/21978, accessed 9 January 2023.

18 Al Gore, An Inconvenient Truth, the movie, December 2006, https://algore.com/library/an-inconvenient-truth-dvd, accessed 9 January 2023.

19 House of Congress, S-1359 Partnerships for Energy Security and Innovation Act of 2021, Washington, 22 April 2021, www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/1359, accessed 9 January 2023.

20 Barack Obama White House, The Recovery Act, Washington, June 2009, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/administration/eop/sicp/initiatives/recovery-act, accessed 9 January 2023.

21 ‘US Department of Energy Announces $42 Million to Develop More Sustainable and Affordable Electric Vehicle Batteries’, ARPA (Washington, October 2022), https://arpa-e.energy.gov/, accessed 9 January 2023.

22 N. Sonnichsen, ‘Average Annual OPEC Crude Oil Price 1960–2020’, ARPA (15 November 2022), www.statista.com/statistics/262858/change-in-opec-crude-oil-prices-since-1960/, accessed 9 January 2023.

23 Drew Bond, ‘Free Economies Are Clean Economies’, C3 Solutions (December 2022), www.c3solutions.org/policy-paper/free-economies-are-clean-economies/, accessed 9 January 2023.