This article was published in Vol. 4 No. 1 of our print edition.

The power to direct US foreign policy is the prerogative of the president, but as Edward S. Corwin famously noted, the US Constitution offers ‘an invitation to struggle for the privilege of directing American foreign policy’.1 This struggle has been fought since the early days of the Republic, with fluctuating congressional influence in foreign policy,2 which has been characterized by debates over internationalism and isolationism along various schools and traditions. Congressional views on NATO in particular deserve special attention in the era of renewed great power competition. The purpose of this article is to offer a clear-cut view of congressional foreign policy arguments on US policy toward NATO.

The foundation of NATO was a crucial milestone in US foreign policy. Firstly, breaking with George Washington’s farewell advice, America created a ‘permanent alliance’, strengthening the US presence and influence across the Atlantic. Secondly, domestic support for NATO settled a fundamental debate. As Senator Arthur Vandenberg noted, ‘politics stops at the water’s edge’, hence in times of geopolitical upheaval, foreign policy and the transatlantic alliance should be free from internal bickering. Yet today’s Congress begs to differ. As the world witnesses a renewal of great power competition, US foreign policy is often short of bipartisan support. This analysis focuses on discussions over NATO from the 115th to the 118th Congress (3 January 2017–present), a timeframe which began with the executive expressing the reality of geopolitics, followed by the legislature demonstrating increased proactivity in foreign affairs.3

Four Camps of Congressional Foreign Policy

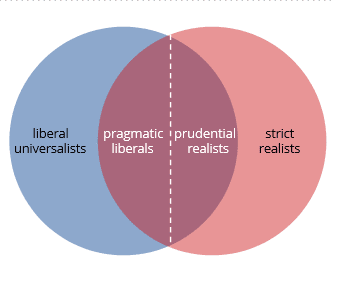

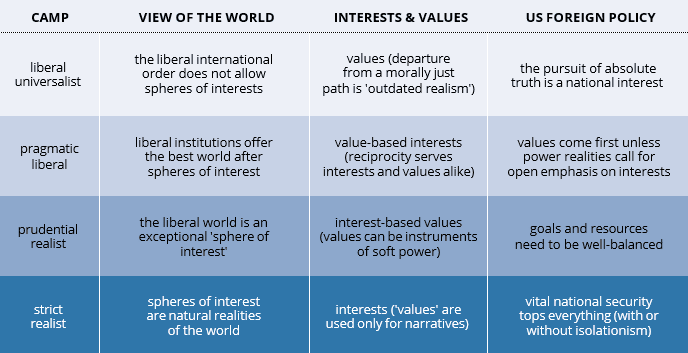

Today the United States faces a revival of factions, not just through a divided government but across the entire body politic. Divisions between and within parties have brought turbulence to public debates and turned Congress into an arena of diverse ideas on US foreign policy. The wide array of opinions can be arranged into four major camps representing different views on how international politics work, how interests and values relate to each other, and how the United States should approach foreign affairs. While having certain basic principles, these groups are neither monoliths nor hierarchical structures (hence the term ‘camps’). Although, they resemble flanks of the Democratic and the Republican Party, the terms used here rely on mainstream IR theories (liberalism and realism).4

The left extreme of the political spectrum is occupied by liberal universalists who are mostly related to progressive Democrats. In their worldview, spheres of interest are outdated concepts oppressing liberty, which is protected by the liberal international order. They not only prioritize certain values, but understand them as interests. Consequently, liberal universalists call for a proactive US foreign policy where the pursuit of moral truths is a national interest and values are at the forefront of any argument.

The centre-left of the political aisle includes pragmatic liberals who are associated with moderate Democrats. Pragmatic liberals agree with liberal universalists that a world based on spheres of interest is a thing of the past and should be avoided in the future. They also connect interests to values, albeit from a different perspective: the liberal international order is in practice the best alternative to other models because reciprocity among members assures that everyone’s values and interests will eventually align. Therefore, the United States should only pursue interests openly when power realities do not allow value-centric arguments.

The centre-right of US politics is home to prudential realists who are mostly mainstream ‘establishment’ Republicans. Being realists, they believe that spheres of interest are eternal features of world affairs but deem the liberal international order exceptional in this regard. Their thinking on values and interests mirrors that of pragmatic liberals: values are defined by interests. As a result, values can take the front seat so long as US soft power—and the prudentially balanced goals and resources—can afford such arguments.

The right extreme of the political spectrum contains strict realists who are often found among the nationalist or Trumpian wing of the Republican Party. Strict realists regard spheres of interests as natural attributes of history and see no differences among the general rationales of great powers. In such a world, foreign policy is dictated by interests, whereas values are merely used to frame narratives in arguments. Therefore, US foreign policy should focus on vital national security interests, which may call for isolationism, although the latter is no overriding principle either.

Congressional Foreign Policy and NATO

The nature of the transatlantic bond and the American rationale for a US presence in Europe is an interesting topic for discussion: historically, the transatlantic order has always corresponded to the changing geopolitical contexts which led the United States from isolation to ad hoc allegiance, and eventually to cooperative security vis-à-vis Europe.5 NATO itself is subject to different interpretations: Lord Ismay’s famous remark that the alliance was meant ‘to keep the Americans in, the Russians out, and the Germans down’ suggests that the US presence in Europe was necessary for outward deterrence and inward balancing alike, in addition to preserving democratic values.6

The four camps of congressional foreign policy suggest different readings on the transatlantic alliance. From a liberal universalist perspective, NATO is not just a political and military alliance focusing on collective defence, but rather a collective security cooperation based on shared values. A pragmatic liberal argument views NATO as an institution where allies’ interests and values can be aligned, whereas a prudential realist understanding highlights the alliance’s role in pursuing US interests in accordance with US values. Lastly, from a strict realist perspective, NATO is the contemporary embodiment of an American sphere of interest in Europe. While the four camps have alternative views on NATO, they do agree that the alliance provides ways and means for realizing American interests across the Atlantic, whether or not values are involved.

The various takes on the transatlantic alliance and the US policy toward NATO have been echoed by congressional initiatives in recent years. The most visible congressional actions were gestures through Senate or House resolutions and congressional diplomacy. Since the legally binding impact of these measures is limited, their number and scope are large, though the ones approved in either house emphasized the US commitment to NATO in terms of liberal arguments. Congress has more binding powers through Article I Sections 8–9 and Article II Section 2 of the Constitution, granting the right to declare war, appropriate federal funds, and ratify treaties (with the Senate’s consent), respectively. Throughout the 115–118th Congresses (3 January 2017–3 January 2025), senators and representatives expressed their views on US financial contributions to the alliance, on the collective defence mechanism under Article 5 of the Washington Treaty of 1949, and on NATO’s most recent enlargements. While pragmatic liberal and prudential realist arguments prevailed, liberal universalist and strict realist ideas also emerged.

Expressing the View of Congress: Gestures to the Alliance and Financing the Alliance

Both houses of Congress have initiated multiple resolutions to express their views on the US commitment to NATO. During the 115th Congress (3 January 2017–3 January 2019), the House voted on H.Res.256 which was agreed without objection on 11 July 2018. House representatives affirmed ‘enduring commitment to and friendship with’ NATO allies and pledged strong US leadership to NATO.7 The day before, the Senate passed a motion that reconfirmed US commitment to NATO and Article 5 of the Washington Treaty. The passage of these nonbinding measures was timed right ahead of the NATO Brussels Summit and served to counterbalance President Donald Trump’s criticism of the alliance.8 In fact, the 115th Congress included several initiatives emphasizing US commitment to NATO and the latter’s importance, though some of these resolutions lost momentum and were never actually passed in either house.9

In addition, both houses introduced several pieces of legislation prohibiting the US withdrawal from NATO, such as H.R.6530 in July 2018. The ‘No NATO Withdrawal Act’ became stuck in the House, but during the 116th Congress (3 January 2019–3 January 2021), the House passed H.R.676, known as the ‘NATO Support Act’, which prohibited the appropriation or use of funds to withdraw the United States from NATO.10 Although this bill did not become law, the Senate passed resolutions lauding and supporting NATO through S.Res.123 and S.Res.122 in 2020 and 2021, respectively. Such congressional moves were reactions to presidential statements, and their number fell in the 117–118th Congresses (3 January 2021–present). Still, there were more specific attempts to influence NATO policy: in April 2022, the Democratic-majority House agreed to H.Res.831, which called on the US government to ‘uphold the founding democratic principles’ of NATO and ‘establish a Center for Democratic Resilience’ within NATO Headquarters.11 It should also be noted, however, that lawmakers on both sides of the aisle (but mainly within the Republican Party) supported resolutions urging allies to meet their defence spending commitments as early as during the 115th Congress.12

‘As…congressional developments on US policy toward NATO show, the struggle over directing US foreign policy continues to be the reality in Washington DC’

The legislature also made public gestures to the alliance through diplomacy. In 2019, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) invited NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg to address US lawmakers. This was another measure balancing presidential rhetoric at the time, although such gestures continued later on. Congressional delegations visited NATO HQ in Brussels in 2022, as well as the Munich Security Conference in 2023, surpassing earlier numbers of US congressional participants. In 2018, Senator Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH) and Senator Tom Tillis (R-NC) revived the NATO Observer Group (1997–2007). While this was yet another reactionary step, its argument (defending Western democracies against the Kremlin while supporting NATO enlargement) and its activity went beyond the response to presidential rhetoric.

Congress has had several opportunities to appropriate funds (or mandate spending) on foreign and security policy programmes. The common pathway for this is to authorize funds for the Department of State through the State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) and the Department of Defense through the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). The annual SFOPS budgets include national contributions to international organizations and peacekeeping operations: the NATO Security Investment Program usually received funding at the requested level (showing increase from FY2022).13 Similarly, the NDAA continued to provide funding for NATO projects, although the NDAA process was also used by US lawmakers to express their views on transatlantic relations.

As the 2024 elections approached and the Biden–Trump rematch took shape, bipartisan efforts to keep the US in NATO regained momentum: the Senate amended its version of the NDAA FY2024 through Senator Tim Kaine’s (D-VA) and Senator Marco Rubio’s (R-FL) S.Amdt.429 which forbade the President to ‘suspend, terminate, denounce, or withdraw the United States from the North Atlantic Treaty’ in July 2023. This was included in the House version of the NDAA FY2024, which was presented to the president in December 2023.14

Strict realists also had opportunities to affect US policy on NATO via the NDAA: Representative Warren Davidson (R-OH-8) sponsored House amendments H.Amdt.245 and H.Amdt.246 which attempted to strike the authorization of funds to NATO’s Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic Initiative and to express the view in Congress that the US should not subsidize NATO members who do not meet the 2014 Wales Summit Defense Spending Benchmark. Both amendments were voted down, albeit with different results: the former failed by 79–353, whereas the latter by 212–218, revealing the Republican (strict and prudential realist) frustration regarding transatlantic burden sharing.15

Ratification and War Powers: Supporting Enlargement and Collective Defence

During the 115–118th Congresses, the Senate received three NATO accession protocols: for the membership of Montenegro in 2017, North Macedonia in 2019, and Sweden and Finland in 2022. The ratification of these documents gained the Senate’s consent by a majority of 97–2, 91–2, and 95–1, respectively. In the case of the first two countries, the main opponents of their accession to NATO were Senator Mike Lee (R-UT) and Senator Rand Paul (R-KY). When arguing against membership, the senator from Utah applied both strict and prudential realist reasoning alike. In his view, Montenegro’s accession not only increases the possibility of Americans being dragged into an armed conflict, but the ‘reactionary statecraft [of opposing Russian positions whatever those are] contradicts the ideals of prudence and practicality’.16 His former staffer, Robert Moore made similar arguments about North Macedonia, emphasizing the importance calculating risks with regard to US national security and economic interests.17

Sweden’s and Finland’s accession seemed less controversial, due to their political and military qualifications. In fact, the majority of US lawmakers rallied to support these countries’ accession efforts through H.Res.1130, which the House passed a month after they were invited to NATO at the Madrid Summit in 2022. The resolution also urged allies to go through their respective ratification processes swiftly.18 Interestingly, the US ratification of NATO’s Nordic enlargement was voted against only by Senator Josh Hawley (R-MO) who believes that the United States should keep its focus on China instead of Europe. In his strict realist reasoning, ‘the geopolitical landscape is very different. Russia is still a threat, but the Chinese Communist Party is a far greater one. And a truly strategic American foreign policy—one that looks to this nation’s strategic interests now, rather than the world of years ago—must embrace this reality, and prepare for it.’19

Meanwhile, Senator Paul opted for a prudential realist line. The Kentucky senator had opposed earlier NATO enlargements, associating them with unnecessary provocations of the Kremlin. However, since Russia’s assault against Ukraine had already changed the strategic landscape, he decided not to oppose NATO’s Nordic enlargement.20 Instead, he used the opportunity to raise a legal issue of committing the United States to Article 5 of the Washington Treaty through an amendment to the accession protocols: S.Amdt.5191 was intended to ensure that NATO’s Article 5 ‘does not supersede the constitutional requirement that Congress declare war before the United States engages in war.’21 The amendment was voted down by 10–87, although its notion echoed through both houses of Congress later on.22 On 22 June 2023, Senator Paul with three co-sponsors and Representative Chip Roy (R-TX-21) with twelve co-sponsors introduced S.Res.266 and H.Res.544, respectively. Both resolutions sought to express the feeling of the Senate and the House ‘regarding the relationship between certain obligations under the North Atlantic Treaty and constitutional declarations of war by Congress’.23 Neither initiative gained momentum, although it should also be noted that debates over the exact process of invoking Article 5 of the Washington Treaty are as old as NATO itself, and have been given a great deal of thought by the American body politic.24

Conclusion

As the highlighted congressional developments on US policy toward NATO show, the struggle over directing US foreign policy continues to be the reality in Washington DC. The 115–118th Congresses worked alongside two distinct administrations, and congressional attempts to influence foreign policy were proactive in both presidential terms. In fact, all four camps in congressional foreign policy thinking have been vocal participants in the debates over US commitment to the transatlantic alliance, whether in the form of gestures, finances, or defence.

Liberal universalists, pragmatic liberals, prudential realists, and strict realists have also found their positions along party lines and factions. While they raised several specific issues throughout the years, the re-occurring themes are consistent with the profiles of the respective wings of both parties: enthusiasm for US commitment to NATO and complaints on transatlantic burden sharing are prevalent sentiments in the United States Congress. Furthermore, the recurrence of such themes shows that despite all their differences, the four foreign policy camps could sometimes reach the same conclusions on US policy toward NATO through their distinctive reasonings.

The approval rates of legislative initiatives suggests that moderates (pragmatic liberals and prudential realists) are still in the majority when it comes to formulating policy toward NATO, at least for now. Nevertheless, the polarization of domestic politics will likely lead to power shifts among these groups which will surely be felt abroad. Therefore, we should not forget that 5 November 2024 is not only an election day to determine who will occupy the White House, but also marks a day when 435 seats in the House and 34 seats in the Senate are on the ballot. Europeans in particular should be prepared for the friends, allies, partners, and critics the 119th Congress may hold for them.

NOTES

1 Edward S. Corwin, The President. Office and Powers 1787–1957 (Fourth revised edition, New York University Press, 1957), 171.

2 James M. McCormick, American Foreign Policy & Process (Fifth edition, Cengage Learning, 2010), 256.

3 The 2017 National Security Strategy was the first such document in the US to publicly declare that the ‘central continuity in history is the contest for power’ or to openly use the words ‘geopolitics’ and ‘geopolitical’ (altogether seven times). The White House, National Security Strategy of the United States of America, Washington DC, 2017. At the same time, certain foreign and security policy actions were mandated by Congress inter alia through the Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act of 2017.

4 For an overview of IR theories (including realist and liberal approaches), see Ole R. Holsti, ‘Theories of International Relations’, in Michael J. Hogan and Thomas G. Paterson, eds, Explaining the History of American Foreign Relations (Second edition, Cambridge University Press, 2004), 51–90.

5 Charles A. Kupchan, ‘The Atlantic Order in Transition. The Nature of Change in U.S.–European Relations’, in Jeffrey J. Anderson et al., eds, The End of the West? Crisis and Change in the Atlantic Order (Cornell University Press, 2008), 112.

6 Lord Robertson, ‘NATO and the Transatlantic Community: “The Continuous Creation”’, Journal of Transatlantic Studies, 1/1 (2003), 5.

7 ‘H.Res.256 – Expressing support for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. 115th Congress (2017–2018), 11 July 2018’, Congress.gov, www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-resolution/ 256?s=4&r=2&q=%7B%22search%22%3A%22nato% 22%7D. Another example of such a resolution was H.Res.397 (sponsored by Speaker of the House Paul Ryan) which had been agreed to in the House in June 2017, a month after President Trump made an address at NATO HQ without mentioning Article 5.

8 Avery Anapol, ‘Senate Votes to Support NATO Ahead of Trump Summit’, The Hill (10 July 2018), https:// thehill.com/homenews/administration/396399-senate- overwhelmingly-passes-resolution-supporting-nato-as-trump/. The two senators voting against the motion were Rand Paul (R-KY) and Mike Lee (R-UT).

9 Examples include, H.Res.202 and H.Rs.1036, as well as S.Res.54 and S.Res.535 introduced in 2017 and 2018.

10 ‘H.R.676 – NATO Support Act. 116th Congress (2019–2020), 22 January 2019’, Congress.gov, www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/676.

11 ‘H.Res.831 – Calling on the United States Government to uphold the founding democratic principles of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and establish a Center for Democratic Resilience within the headquarters of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. 118th Congress (2023–2024), 5 April 2022’, Congress.gov, www.congress. gov/bill/117th-congress/house-resolution/831.

12 Examples include H.Res.135 and S.Res.570 introduced (but never approved) in 2017 and 2018.

13 According to the 2018–2023 Consolidated Appropriations Acts, available online Congress.gov.

14 ‘H S.Amdt.429 to S.Amdt.935. 118th Congress (2023–2024), 19 July 2023’, Congress.gov, www.congress.gov/amendment/118th-congress/senate-amendment/429/actions?s=5&r=1&q=%7B%22search%22%3A%22tim+kaine%22%7D; and ‘H.R.2670 – National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024. 118th Congress (2023–2024), 14 December 2023’, Congress.gov, www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/2670.

15 ‘H.Amdt.245 to H.R.2670. 118th Congress (2023–2024), July 13, 2023’, Congress.gov, www.congress.gov/amendment/118th-congress/house-amendment/245?r=2&s=a&r=16; and ‘H.Amdt.246 to H.R.2670. 118th Congress (2023–2024), 13 July 2023’, Congress.gov, www.congress.gov/amendment/118th-congress/house-amendment/246?r=2&s=a&r=15.

16 Mike Lee, ‘Floor Statement on Montenegro accession to NATO, 28 March 2017’, Lee.Senate.gov, www.lee.senate.gov/2017/3/floor-statement-on-montenegro-accession-to-nato.

17 Robert Moore, ‘Admitting North Macedonia to NATO Brings More Risks than Benefits to the US’, The Hill (31 October 2019), https://thehill.com/opinion/international/468270-admitting-north-macedonia-to-nato-brings-more-risks-than-benefit-to-the/.

18 ‘H.Res.1130 – Expressing support for the sovereign decision of Finland and Sweden to apply to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) as well as calling on all members of NATO to ratify the protocols of accession swiftly. 117th Congress (2021–2022), 18 July 2022’, Congress.gov,www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-resolution/1130?s=1&r=24.

19 Josh Hawley, ‘Why I Won’t Vote to Add Sweden and Finland to NATO’, The National Interest (1 August 2022), https://nationalinterest.org/feature/why-i-won%E2%80%99t-vote-add-sweden-and-finland-nato-203925.

20 Rand Paul, ‘Should NATO Admit Sweden and Finland?’, The American Conservative (14 July 2022), www.theamericanconservative.com/should-nato-admit-sweden-and-finland/.

21 ‘S.Amdt.5191 to Treaty Document 117–3. 118th Congress (2023–2024), 3 August 2022’, Congress.gov, www.congress.gov/amendment/117th-congress/senate-amendment/5191/ text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%22nato%22%7D.

22 ‘S.Amdt.5191 to Treaty Document 117–3. 118th Congress (2023–2024), 3 August 2022’.

23 ‘S.Res.266 – Expressing the sense of the Senate regarding the relationship between certain obligations under the North Atlantic Treaty and constitutional declarations of war by Congress. 118th Congress (2023–2024), 22 June 2023’, Congress.gov, www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-resolution/266/text?s=1&r=37; and ‘H.Res.544 – Expressing the sense of the House of Representatives regarding the relationship between certain obligations under the North Atlantic Treaty and constitutional declarations of war by Congress. 118th Congress (2023–2024), 22 June 2023’, Congress.gov, www.congress. gov/bill/118th-congress/house-resolution/544/ text?s=1&r=1&q=%7B%22search%22%3A%22H. Res.544%22%7D.

24 Michael J. Glennon, ‘The NATO Treaty Does Not Give Congress a Bye on World War III’, Lawfare (23 March 2022), www.lawfaremedia.org/article/nato-treaty-does-not-give-congress-bye-world-war-iii.