This article was published in Vol. 4 No. 3 of our print edition.

Changing Global Supply Chains and Geopolitical Implications

Introduction

Ours is an era of transitions: from modern to postmodern,1 from industrial to post-industrial, from unipolar to multipolar. This latter view neither builds on the exclusivity of American power nor sees China as the next hegemon replacing the United States, but rather places the US–China competition in a broader context. It anticipates a greater dispersion or shift of power from Europe to Asia, from the West to the ‘Rest’, and from state actors to non-state actors. In addition, we are at the peak of a technological revolution and the culmination of digitization, the fusion of man and machine, an ever more rapidly widening income and social gap, and the mass impoverishment that comes with it. The list goes on.

For some time now, we have been sure that the end of history has not yet come, but at the same time, social distortions arising from the shortcomings of liberal ideology are coming to the surface, especially in the West. However, one still seemingly solid pillar among the main buttresses of liberalism is the idea of ‘the economy as fate’ or ‘the economy as destiny’.2 It seems that the Cold War was not won by liberalism or democracy, but by capitalism, the economic system based on (unrestricted) growth.3 The current great powers all operate their economies based on the capitalist system. Naturally, there are differences between their systems. For example, China has its own, unique economic system, but overall, all the major—capitalist—powers, and indirectly the countries dependent on them, are at least interested in the well-oiled operation of the global trade system and the smooth functioning of the global financial system. Currently, this shared faith amongst them is the one thing the world unconditionally shares, forming a vast unified, interconnected system due to globalization. Its maintenance is in everyone’s interest.

But it could easily be that even this is now just a memory because at present it seems that the United States, as one of the main creators and beneficiaries of the system, has begun to dismantle the framework of the integrated world economy.4 The processes of transition—such as the transformation of the world order and the associated political, military, economic and ideological struggles—are taking place before our very eyes, day by day. In this context, it is worth examining whether the economy is also following the fragmentation characteristic of the postmodern era, which in this area can be paralleled with the process of ‘decoupling’, or whether its interconnectedness has already reached such a level that it makes it impossible for it to break down into smaller subsystems (of course, all this in such a way that the smaller systems generate the same economic outcome, i.e. this does not lead to a decrease in living standards and profits).

China and the United States are at the centre of the transformation processes, as the number one challenger and the current hegemon. The growing international tension arising from their competition (also) raises a number of political, economic, and strategic questions for both countries and for the global community. In my article, I would like to examine the complexities and implications of the US–China trade war and the decoupling efforts initiated by the United States. I argue that while the primary aim is to reduce US reliance on Chinese imports, the interconnected nature of global supply chains and economic interdependence challenges the feasibility of complete disengagement, suggesting that alternative strategies such as strengthening alliances and promoting multilateral cooperation are necessary to navigate the evolving global trade landscape.

The New Challenger

Let us briefly analyze Chinese–American economic relations as operational mechanisms of the world’s two largest powers. The relationship between China and the United States is globally decisive. In recent years, this relationship has become increasingly strained, as the two countries have competed for economic and technological supremacy. This has led to a number of challenges, including trade tensions, tariffs, and a decoupling of supply chains. First, let us see how China came to its challenger position, and why the United States felt that China posed a strategic challenge to it.

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, China has achieved astonishingly rapid economic growth, carving out an increasingly large slice of the global economy for itself. This development has resulted in competition with the United States in several areas, particularly in key industries such as technology, telecommunications, and energy. In recent years, Chinese–American relations have been influenced by trade tensions, tariffs, and competition for technological dominance. This has also affected global supply chains, which faced additional challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting economic problems stemming from the vulnerability of supply chains. This vulnerability has revealed how interconnected the global economy is, and consequently, how vulnerable everyone is to any interruption affecting the smooth functioning of the system.5

From the perspective of supply chains, almost every country is a key player, but China and the United States have particularly prominent roles. The former is one of the world’s largest exporters and manufacturing centres, especially in electronics, apparel, and other consumer goods. The latter provides a significant market and technological innovation. The tense economic competition between the two countries, the process of decoupling, and the issue of supply chains have brought to the surface the challenges and problems of globalization and complex international economic relations. It is becoming increasingly clear that economic isolation from China could result in increased political and military tensions in the Asian region or even globally. This is especially true regarding the disputed areas around the South China Sea. These signs indicate an attempt to transform and reshape the world order.6

The Transforming World Order

Based on the events of recent years, we can assert that the unipolar world order that has prevailed since the 1990s, led by the United States and often referred to as ‘the West’, is in a state of disintegration. To avoid misunderstandings, this does not mean that the United States and the Western-led world order will collapse with a great bang. Instead, the process takes the form of a slow decline. It must be emphasized, however, that we are talking about a relative decline, and by disintegration, we specifically mean the loss of the former hegemonic role, combined with a kind of ideological crisis that goes hand in hand with a radical transformation of the architecture of the global order.

The outlines of the new power relations are not yet clear. But whatever the transformation, it is very likely that the West will retain its geopolitical weight, but will no longer possess exclusive power and must take into account the will of other power centres. What we are witnessing is the birth of a new global order. We live in an era in which the old order is fading away—this gives a shimmering reflection of its existence—but the new one has not yet emerged, and is taking shape before our very eyes.

There are two causes underlying the disintegration of the world order. Firstly, the global economy, based on global value chains, is completely exhausted. Some argue that the global economy has never truly globalized over the past fifty years, but has instead regionalized, meaning that trade was not spreading evenly everywhere, but was concentrating within regions. However, what is certain is that the current trend is towards the regionalization of the global economy. Regional trade agreements such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) are fostering closer economic ties within Asia, while the USMCA is strengthening trade links between the United States, Mexico, and Canada. These agreements simplify trade processes and reduce tariffs, promoting regional economic integration.7

For businesses, internationalization continues to be beneficial in terms of cost efficiency, talent acquisition, and profitability. Governments, on the other hand, are finding that regionalization supports national security, supply chain resilience, and economic competitiveness. This balanced approach allows states to protect their national interests while still reaping the benefits of international trade, indicating that regionalization is the sustainable path forward in the current geopolitical landscape.8

This leads to the second reason: the stagnation of the processes of globalization, or so-called ‘slowbalization’, meaning that the system cannot be sustained based in its existing forms or regularities. In conclusion, while the data do not yet show a clear trend towards deglobalization, the profound changes in policy and public sentiment suggest a new phase of globalization characterized by an increased emphasis on national security, economic resilience, and strategic trade relationships. This raises the question: what will be the new structure of the world? Roughly, we can consider two possibilities. One option is that globalization and the process of globalization persist, but the world’s structure becomes multipolar, known as a multipolar world order. The other possibility is that the world breaks down into so-called great spaces, macroeconomic large regions, or great-power geopolitical spheres of influence. This would mean a significant loosening of the world’s economic interdependence and, in some areas, almost complete separation (this would be one of the aims of the aforementioned decoupling process).9

This transformation and rearrangement process is currently taking on the form of a new Cold War. Its possible beginning can be traced to the year 2018, which also saw the beginning of the US–China trade war. It is worth emphasizing that the most defining characteristics of this conflict are geopolitical and power-related, and only secondarily ideological (though the ideological aspect should not be neglected altogether).10 What is certain, however, is that we can speak of a confrontation between the world’s two largest economic powers. The order is by no means clear because if we calculate GDP based on nominal exchange rates, the United States is ahead, but if we consider purchasing power parity (PPP), then China’s economy is larger. But there is no need for us to declare a winner; it is enough to acknowledge that it is a battle between giants, with global repercussions.

Furthermore, China’s military and diplomatic influence has significantly increased in recent years, alongside its economic influence, bringing about changes that are also felt globally. Militarily, China has made significant investments in developing its defence capabilities, including the acquisition of modern military technology and the modernization of its armed forces. China has the world’s second-largest military budget and is actively developing strategic capabilities such as cyber defence, space technology, and long-range missile systems to maintain a global military presence. However, it should be noted that China has not waged war anywhere in the world for forty-five years, making it difficult to precisely assess what it would be capable of in the event of an actual conflict. Nonetheless, China prefers to increase its influence and achieve its goals through economic and diplomatic means rather than militarily.11

On the diplomatic front, China’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ exerts significant influence on world politics, particularly through infrastructure development projects, which enable it to gain economic and political leverage in participating countries. Additionally, China is an active participant in international forums and organizations, such as the UN, where it seeks to shape global political and economic systems through diplomatic efforts. We can also mention the BRICS and Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), in which China plays a key role and aims to build an alternative global order with their help. Not to mention one of their significant endeavours: the removal of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, or at least developing alternative payment rails and pricing benchmarks,12 which would profoundly affect the United States and exacerbate its debt burden. China’s diplomatic strategy includes building close bilateral relations with various countries and participating in multilateral trade agreements and regional security pacts, thereby enhancing its international authority.

Overall, China’s economic, military, and diplomatic influence has dynamically expanded in recent times, presenting new challenges and opportunities for the international community. These efforts by China indicate a potential rearrangement of the global balance of power, which the countries of the world should pay attention to when shaping international relations and security strategies.13

For the above reasons, we can assert that China is one of the main promoters and engines of the transformation of the world order. China, by its sheer size alone, demands a place on the world stage, but it not only seeks a place, it aims to actively shape the new power structure.14

Conflicts occurring worldwide (such as in Ukraine or the Middle East) only reinforce this process and may even render it irreversible. Therefore, in spring 2023, China made a strategic decision to openly advocate for the transformation of the world order. In other words, it primarily seeks to cooperate closely with countries interested in changing the current world order, including deepening its ties with the Global South.15

This endeavour was further intensified by the Biden administration’s declaration of China as its primary challenger. It sees China as the only actor capable of posing complex economic, military, and political challenges to the US.16

China understood the implications and decided to take up the challenge—at least economically. It still prefers negotiation and peaceful methods over open military conflict. This preference partly stems from the existential character, philosophy, and cultural traditions of China, rooted as they are in Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism. These philosophies not only shape Chinese thinking internally but also manifest in international relations and diplomacy as preferred methods of conflict resolution. In simplified terms, they aim to maintain a unique state of peace, harmony, and balance in the world.17

On the other hand, practical reasons for China’s behaviour include maintaining social and economic stability and security in the region—and potentially worldwide—as China needs time to catch up militarily and technologically with the United States. Therefore, while China is a key catalyst for change, it does not rush; it exercises strategic patience. It can afford to do so because while the West, led by the US, is still in a hegemonic position, it is in a civilizational decline, whereas the position of the China-led Eastern bloc and the Global South is still weaker, but has entered an integrative phase, and is growing stronger and coordinating its steps. This contrasting movement may also explain the increasing tensions globally.18 In the next section, we shall backtrack a few years and examine how the conflict between China and the United States erupted, leading to the emergence of the decoupling process.

The US–China Trade War

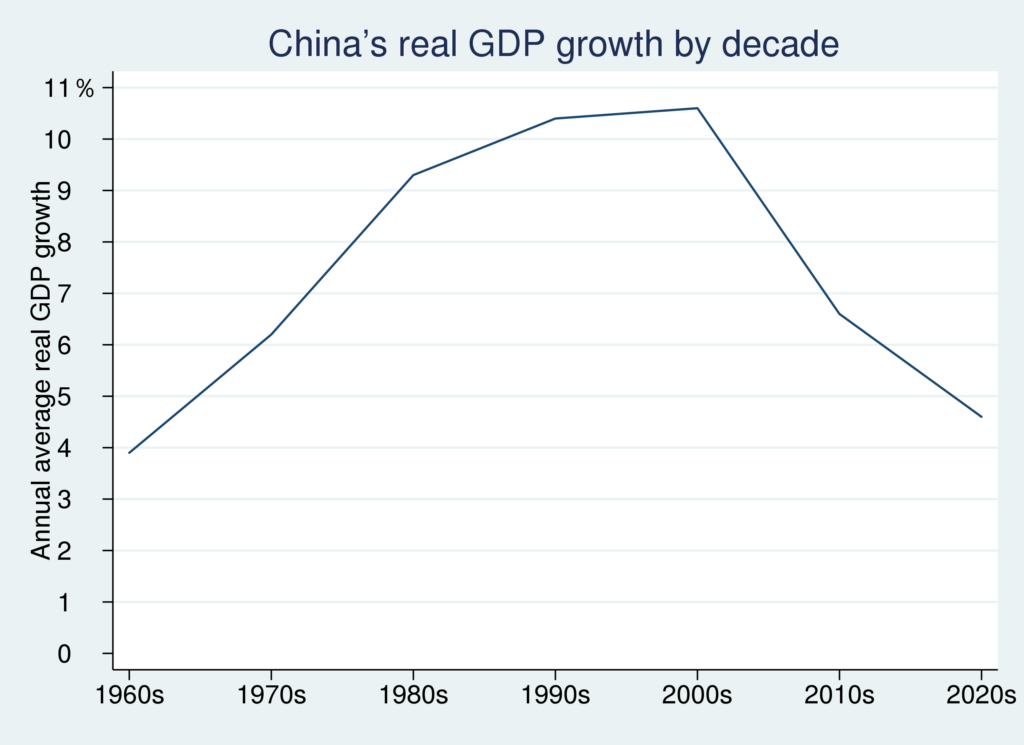

It is beyond our scope here to detail the steps of China’s economic miracle. The essence is that China has achieved economic growth over the past forty years at an unprecedented rate in world history, averaging 9.5 per cent annually.19

In short, China has indeed surpassed the United States and has become its number one rival, with numerous analyses suggesting that it will clearly outpace it in the next decade.20 In this atmosphere, the Trump administration committed itself to implementing a series of measures against China, known as ‘decoupling’. This is a complex economic and political strategy aimed at reducing mutual dependence between the American and Chinese economies in certain key areas. The process particularly focuses on critical sectors such as technology, manufacturing, and trade, with the goal of reducing the US’s vulnerability to China and strengthening its own economic security and strategic autonomy. It is important to mention that the decoupling policy is an endeavour that the Biden administration has almost unequivocally inherited from Trump. We can mostly talk about shifts in emphasis, with Biden focusing on (peak) technological restrictions (the ‘chip war’) and trying to rebrand the endeavour from ‘decoupling’ to ‘derisking’.21

Decoupling measures include trade restrictions, tightening the export of critical technologies, introducing investment limits, diversifying supply chains, and reshoring manufacturing capacities, as well as expanding into alternative markets (nearshoring, friendshoring). The aim of these measures is to minimize America’s dependence on China, especially in sectors critical to national security or innovation.22

The underlying idea behind the decoupling initiative is that it is vital for the United States to maintain economic and technological sovereignty and to ensure competitive advantages in the strategic rivalry with China. In essence, the United States seeks to preserve its preeminent position on the world stage.23 But let us take a closer look at how feasible the idea is in reality, now with a six-year perspective.

Enter Trump: ‘Trade Wars Are Good, and Easy to Win’24

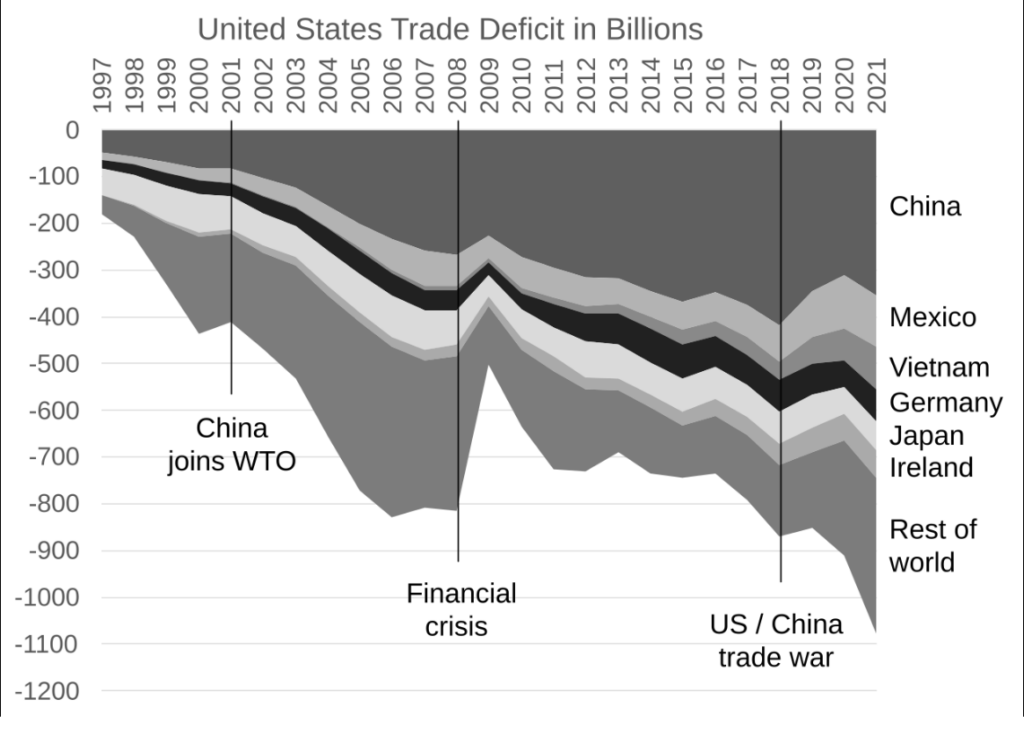

In March 2018, Donald Trump announced the imposition of trade sanctions against China, welcoming Chinese President Xi Jinping with the utmost respect, but then addressing the historic low in the Chinese–American trade balance, specifically showing a deficit of $376 billion with China.25 He immediately sought to reverse this trend and decided to introduce new punitive tariffs on goods imported from China in three rounds, totalling $250 billion, thereby initiating a trade war between the two countries. It is worth noting that Trump had promised protectionist measures during his election campaign, but the public did not take this seriously.26

Part of the punitive package was imposing a 25-per-cent tariff on steel and an additional 10 per cent on aluminium. This naturally did not only affect Chinese goods. In fact, due to the tariffs introduced, the US market lost about $14.2 billion worth of steel imports, of which China accounted for only a 5-per-cent share, or less than $700 million. Thus, the decision led to a peculiar situation where the allies of the US (such as Canada, South Korea, Japan, and Germany) suffered much greater losses. The EU immediately lodged a complaint with the WTO Dispute Settlement Body, stating that Trump’s unfair decision endangered thousands of jobs. But the US remained uncompromising.27

Currently, there is often talk of a reversal of globalization, reshoring production, or establishing new supply chains with neighbouring countries (nearshoring) to replace the losses resulting from the decoupling process. Moreover, recently Janet Yellen has started using the term ‘friendshoring’, which entails building economic relationships where shared ideology plays an important role.28 This also indicates an attempt to create a bloc with ideologically reliable partners. However, the reality—the geographical separation of production and management functions developed over decades due to globalization29—is much more complex than simply being able to fully replace decades-long relationships with tariffs and some restructuring of supply chains.

Facts, unlike news headlines, are stubbornly hard to change, and trade data does not indicate an efficient transformation process. Global merchandise trade soared to record heights in 2022, and US imports exceeded pre-pandemic levels by nearly 40 per cent. In addition, the historical trade deficit highlighted by Trump—$372 billion—peaked in 2022 and increased by $10 billion to $382 billion.30 While the 2023 data show a drastic decrease, reducing the deficit to ‘only’ $280 billion,31 we still do not know if this represents a longer-term trend.

There was also no significant decline in China; their exports to the United States have increased by 30 per cent since 2017, despite the tariffs. So a transformation is underway, but not necessarily the one the United States expected. There is also another, less widely considered possibility: that a trade war with China will entail such serious losses for both parties that it may inadvertently benefit a third, currently overlooked party in the medium or long term.32

Little Known Facts About Decoupling: Unveiling the Hidden Impacts on Global Trade Supply Chains

The US–China trade war and the ensuing decoupling efforts have undoubtedly reshaped global trade dynamics. While the primary goal was to reduce US reliance on Chinese imports, the broader implications of decoupling extend far beyond this initial objective. This short analysis delves into the lesser-known aspects of decoupling and its often-unforeseen consequences on global trade supply chains.

Signs of US–China decoupling were first observed when China’s share of American imports began to decline in 2018. China’s share of US imports decreased from 21.6 per cent to 13.2 per cent—an 8.4-per-cent decrease—between 2017 and 2023, and has now fallen back to roughly the level it had reached before the 2007 global financial crisis. This decline was particularly dramatic for strategic products (goods identified by the US government as advanced technological products), dropping from 36.8 per cent in 2017 to 23.1 per cent in 2022, representing a decrease of more than 13 per cent.33

The decline in China’s share of imports into the United States focused on goods subject to tariffs. In 2022, US imports of dutiable goods from China were 12.5 per cent lower than in 2017, while imports from the rest of the world for similar products increased. A similar pattern is not evident for non-tariffed products, where the change in Chinese imports does not seem to differ significantly from imports from the rest of the world. The significant decrease in China’s share of dutiable products and the overall growth of American imports collectively suggest that tariffs forced importers to turn to new sources of procurement; or in other words, to accelerate the decoupling process.34

The US was primarily able to offset the loss of Chinese imports with the help of seven countries. These are, in order, Vietnam, Taiwan, Canada, Mexico, India, South Korea, and Thailand. Focusing on total market share, Vietnam (1.9 per cent) and Taiwan (1 per cent) increased their overall market share. Canada (0.75 per cent), Mexico (0.64 per cent), India (0.57 per cent), South Korea (0.53 per cent), and Thailand (0.5 per cent). These seven countries account for the backbone of China’s 8.4-per-cent decline. In terms of strategic goods, Vietnam and Taiwan gained the largest market share in the United States during the period under review.35

However, we must emphasize again that building a well-functioning supply chain can take years or even decades. Replacing it—never mind making the replacement system function smoothly—poses an almost insurmountable challenge for economic actors. Therefore, changing the deep structure of supply chains is very difficult.

Looking more closely, we see that the reorganization of US imports did not coincide with an increase in the diversification of American import sources. Take a look at the Herfindahl–Hirschmann indexes (HHI), which are used to measure the market share of players in a particular economic sector. This is one of the measures used to filter out the monopolistic position of certain companies. The HHI value ranges from zero to one, where a value close to one indicates the formation of a monopoly position, while values close to zero indicate many small market shares. Average HHI’s for products show little variation in recent times. Tariffed goods generally have a more diversified supplier base than tariff-free goods (indicating that limited diversification was not necessarily the key reason for imposing tariffs). However, for both dutiable and non-dutiable products, the HHI decreased only slightly during the period (2017–2022), clearly indicating that import diversification remained relatively stable regardless of tariffs. This means that no truly profound structural changes have occurred.36

Finally, I would like to mention a connection that receives little or no attention, yet adds an unexpected twist to the story. The aforementioned countries that helped the US offset the decline in Chinese exports to meet the increased demand for imports intensified their trade relations with China. So instead of decreasing its dependence on China, US dependency has indirectly strengthened because the leading countries in US exports have to maintain closer ties with China, as it has become an indispensable element in global supply chains.

The article also points out that in electronics—which contributed most to decoupling and includes many strategic products—the countries that increased exports to the United States also increased imports from China in the sector. This high correlation suggests that relationships with China have become particularly important for those replacing China in the US market. In other words, to squeeze out China from the export side, these countries have built extensive supply chains with China across entire industries.37

Decoupling VS. Dependency: Unravelling the Nuances

So far, I have tried to uncover the impact of US tariffs on trade with China and on global trade systems. The findings paint a nuanced picture, revealing the tension between economic efficiency and complete disengagement, often referred to as ‘decoupling’. While tariffs undoubtedly led to a decrease in US imports of dutiable goods from China, the United States did not significantly expand the sources of these imports. There is also limited evidence that the US has reshored production to reduce its dependence on China and strengthen its domestic markets. Instead, it appears that the trade landscape is changing. Countries with natural advantages in producing certain goods have gained market share as the United States has reduced imports from China. This highlights the power of comparative advantages in global trade.38

However, the situation becomes more complicated when we examine strategic sectors such as those involving advanced technologies. Here, tariffs had a more tangible impact on US imports from China. Yet even in these sectors, there is a lack of clear evidence of reshoring production. Interestingly, some countries that increased their exports to the United States in these strategic sectors have developed closer trade ties with China in these areas. This suggests the existence of complex network structures within existing supply chains that cannot be easily disrupted or dismantled solely through protective tariffs and restrictions. Furthermore, imports from China have increased in these countries, likely indicating transit trade or other adjustments within global supply chains.39

This article highlights some of the challenges of completely disconnecting from the Chinese manufacturing base. Such a shift would not only be lengthy but also costly, requiring considerable political will, signs of which are not yet evident—or only at the rhetorical level and in some partial successes. Moreover, reducing direct imports is unlikely to significantly change dependence on Chinese supply chains, which are deeply embedded in the global trade network. While tariffs may disrupt trade patterns, the picture is much more complex than a simple narrative of independence.

Summary

In summary, the integrative role of the economy somewhat hinders complete global fragmentation, and decoupling is currently more rhetoric than reality. However, these opposing civilizational movements—the loss of US hegemony, and the strengthening of the China-led multipolar vision—will inevitably lead to further sources of conflict. If the West wants to maintain its geopolitical weight and address its internal tensions, it should focus primarily on solving its own structural problems (demographic issues, maintaining a competitive economy, wage adjustments, pruning ideological excesses, creating constructive dialogue between the elite and the common people, etc.), rather than transforming these internal problems into a global geopolitical conflict. External conflicts and total attempts to dominate the planet will not only fail to solve internal tensions but will ultimately exacerbate them. If, on the other hand, the West is not capable of self-restraint and a constructive approach to the global community, then a series of further conflicts can be expected. For as we can see, the challengers are emerging with increasingly assertive foreign policy concepts which they are not afraid to formulate against the West, and, as noted, time seems to be on their side.

NOTES

1 Here I am using the classical interpretation of modernity, wherein the concept of the modern is rooted in the idea of capitalist and industrial development, and in the democratic revolutions of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in the West (Europe and North America) and characterized by the increasing flow of goods, people, capital, and information—similar to globalization (Peter Wagner, Modernity: Understanding the Present [Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012], 3). This focus on economic freedom and capitalism coincides with the erosion of traditional social structures and the rise of the nation-state. In contrast, postmodernity, or high modernism, unlike other approaches, cuts across traditional political ideologies. It aims to remake society entirely based on a utopian vision, which can vary greatly depending on one’s political views. However, projects aligned with high modernism often require authoritarian and technocratic leadership, as they rely on a high degree of control and societal change that can be difficult to achieve democratically. See: James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State. How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (Yale University Press, 2020), 5, 94.

2 Gábor Czakó, Mi a helyzet? Gazdaságkor titkai (What Is the Situation? Secrets of the Age of Economics) (Boldog Salamon Kör, 2001).

3 Berry Buzan, ‘The Role of the Military in a Post-Western Global Order’, YouTube (19 February 2019), www.youtube.com/watch?v=xZBcIwT31NM.

4 Simeon Djankov et al., ‘The United States Has Been Disengaging from the Global Economy’, Peterson Institute for International Economics (19 April 2021), www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/united-states-has-been-disengaging-global-economy.

5 John Lee, ‘Decoupling the US Economy from China after COVID-19’, Hudson Institute (May 2023) http://media.hudson.org.s3.amazonaws.com/Lee_Decoupling%20the%20US%20Economy%20from%20China%20after%20COVID-19.pdf.

6 Ronald O’Rourke, ‘US–China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress’, Congressional Research Service Report (28 May 2020), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/ R42784.

7 Shannon K. O’Neil, ‘It’s Not Deglobalization, It’s Regionalization’, Yale University Press (26 October 2023), https://yalebooks.yale.edu/2023/10/26/its-not-deglobalization-its-regionalization/.

8 O’Neil, ‘It’s Not Deglobalization, It’s Regionalization’.

9 Pinelopi K. Goldberg, and Tristan Reed, ‘Is the Global Economy Deglobalizing? And If So, Why? And What Is Next?’, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 31115 (April 2023), www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31115/w31115.pdf.

10 Sándor Kusai, ‘Az új hidegháború kérdéséről’ (About the Question of the New Cold War), Külügyi Szemle, 2 (2021), 3–21.

11 Falk Hartig, ‘How China Understands Public Diplomacy: The Importance of National Image for National Interests’, International Studies Review, 18 (2016), 655–680, https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viw007.

12 Lucy Corkin, ‘BRICS and De-dollarization: Global Implications’, Observer Research Foundation (23 February 2024), www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/brics-and-de-dollarisation-global-implications.

13 Anthony H. Cordsman, ‘China’s Emergence as Superpower. A Graphic Comparison of the United States, Russia, China and other Major Powers’, CSIS (11 August 2023), https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2023-08/230811_Cordesman_China_Emerging. pdf?VersionId=PfyIjoITze29gpLxIY8kFOsuXzqLikV5.

14 Brad Glossermann, ‘What Is Beijing’s Ultimate Endgame. The Answer Is Clear’, Japanese Times (27 March 2024), www.japantimes.co.jp/commentary/2024/03/27/world/what-china-wants/.

15 Michael Schuman, Jonathan Fulton, and Tuvia Gering, ‘How Beijing’s New Initiatives Seeks to Remake the World Order’, Atlantic Council (21 June 2023), www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/how-beijings-newest-global-initiatives-seek-to-remake-the-world-order/.

16 ‘The Biden-Harris Administration, National Security Strategy, 12 October 2022’, The White House, www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf.

17 Tingyang Zhou, ‘A Political World Philosophy in Terms of All-under-heaven (Tian-xia)’, Diogenes, 56 (2009), 5–18.

18 Kishore Mahbubani, The Asian 21st Century. China and Globalization (Springer, 2022).

19 National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Transport, ‘China’s Economic Development in 40 Years’, China Daily (2018), www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/chinaecoachievement40years/index.html.

20 Andrew Scobell et al., ‘China’s Grand Strategy. Trends, Trajectories and Long-Term Competitions’, Rand Corporation (24 July 2020), www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2700/RR2798/RAND_RR2798.pdf.

21 Philip Pilkington, ‘The Risk of Decoupling and De-risking’, Hungarian Institute of International Affairs (March 2024), https://hiia.hu/wp-content/ uploads/2024/03/connectivity_p_2024_02_v7.pdf.

22 Jon Bateman, ‘U.S.–China Technological “Decoupling”. A Strategy and Policy Framework’, Carnegie Endowement for International Peace (25 April 2022), https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2022/04/us-china-technological-decoupling-a-strategy-and-policy-framework?lang=en.

23 John Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (W. W. Norton & Company, 2003).

24 See Trump’s infamous Twitter post on the matter: https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/969525362580484098.

25 ‘Remarks by President Trump at Signing of a Presidential Memorandum Targeting China’s Economic Aggression, 22 March 2018’, The White House, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-signing-presidential-memorandum-targeting-chinas-economic-aggression/.

26 Hang Nguyen, ‘Donald J. Trump and Asia: From Campaign to Government’, Asian Affairs: An American Review, 44 (2017), 125–141, https://www.jstor.org/stable/48538838.

27 Chad P. Bown, ‘Trump’s Steel and Aluminum Tariffs Are Counterproductive. Here Are 5 More Things You Need to Know’, Peterson Institute for International Economics (7 March 2018), www.piie.com/blogs/trade-and-investment-policy-watch/trumps-steel-and-aluminum-tariffs-are-counterproductive.

28 ‘Transcript: US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen on the Next Steps for Russia Sanctions and ‘Friend- Shoring’ Supply Chains’, Atlantic Council (13 April 2022), www.atlanticcouncil.org/news/transcripts/transcript-us-treasury-secretary-janet-yellen-on-the-next-steps-for-russia-sanctions-and-friend-shoring- supply-chains/.

29 In other words, the formation of global value chains.

30 U.S. Department of Commerce, US Trade with China (2022), BIS.doc.gov, www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/country-papers/3268-2022-statistical-analysis-of-u-s-trade-with-china/file.

31 Xin Ou, ‘United States Goods Trade Deficit with China from 2013 to 2023’, Statista (1 March 2024), www.statista.com/statistics/939402/us-china-trade-deficit/.

32 Kira Schacht, ‘The Real Winners of the China–U.S. Trade Dispute’, Deutsche Welle (29 October 2020), www.dw.com/en/the-real-winners-of-the-us-china-trade-dispute/a-55420269.

33 Caroline Freund et al., ‘US–China Decoupling: Rhetoric and Reality’, The Centre for Economic Policy Research (31 August 2023), https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/us-china-decoupling-rhetoric-and-reality.

34 Caroline Freund et al., ‘Is US Trade Policy Reshaping Global Supply Chains?’, World Bank Group, East Asia and the Pacific Region and the Prospect Group (October 2023) https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099812010312311610/pdf/IDU0938e50fe0608704ef70b7d005cda58b5af0d.pdf.

35 Freund et al., ‘US-China Decoupling: Rhetoric and reality’.

36 Freund et al., ‘US-China Decoupling: Rhetoric and reality’.

37 Freund et al., ‘US-China Decoupling: Rhetoric and reality’.

38 Mary E. Lovely, ‘Manufacturing Resilience: The US Drive to Reorder Global Supply Chains’, Aspen Economic Strategy Group (8 November 2023), www.economicstrategygroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Lovely_2023_Chapter.pdf.

39 Joe Seydl, and Zidong Gao, ‘Is the World Economy Deglobalizing?’, J. P. Morgan (24 January 2024), www.jpmorgan.com/insights/outlook/economic-outlook/is-the-world-economy-deglobalizing.