This article was published in our print edition’s Special Issue on the European Union.

The criticisms of Hungarian democracy by the EU have become so familiar that perhaps there is not a single primary school pupil in Europe who has not heard them. On the other hand, the European public is less familiar with the fact that the criticism is mutual: in Hungary, most of society and the government view the state of democracy operating in the institutions of the EU with growing concern and mounting criticism. This mutual criticism increasingly defines the relationship between Hungary and the system of EU institutions in Brussels.

‘We must start from the fact that we are a free country, and this country belongs to us, Hungarian citizens’

Before delving into the details of the latter, it is important to first be aware of the trap that we Hungarians must absolutely avoid in connection with this conflict, which is that due to the mostly unfounded, unjust, and illegal pressure exerted on us by Brussels, we imagine our own domestic democracy to be perfect. But a perfect democracy is a pipe dream. Like any machine put to constant use, democracy degrades over time, and so must be maintained: sooner or later, illegitimate domestic and foreign interests always find and start exploiting the loopholes, which must be closed again and again. We would be letting Brussels dictate our course not only if we yielded to its demands without consideration, but also if, for the same reason, we considered everyone who points out problems with the functioning of Hungarian democracy and calls for solutions to be an agent of Brussels from the outset. That would mean no constructive debate about the state of democracy, and ultimately our attempts to ‘uphold’ our democratic state would fail.

We must start from the fact that we are a free country, and this country belongs to us, Hungarian citizens. Citizens elect a government majority every four years in order to consider domestic and foreign criticisms—but above all domestic—and decide which it would benefit and which harm the country to heed. If EU criticisms prevent us from dealing freely with the state of our own democracy, they can easily become a self-fulfilling prophecy! In addition, as a result of our accession to the EU, the community of Hungarian citizens has for two decades not only been the owner of Hungarian democracy, but also a co-owner of the EU. Therefore, the democratic functioning of the EU’s shared institutions also falls within the scope of Hungarian democracy.

‘Hungarian history is full of constitutional revolutions—periods when, acting within the framework of the old (obsolete or inherently flawed) constitutional order, we created something radically different from it: a new, better, more democratic constitutional order’

Within the EU institutions, democracy is likewise in constant use, and therefore wears out over time, meaning that it needs maintenance, just like our democracy at home. The fact that we are only co-owners makes maintenance in Brussels somewhat more complicated than in Hungary, so we have to take care of taking diagnoses and ‘maintenance’ work together with the other twenty-six member states. During earlier stages of the European project, the metaphor of ‘the European House’ was often used as a kind of communal self-definition, but the term ‘European apartment block’ might be more appropriate. And at the general residents’ assembly of this apartment block—i.e. the joint decision-making institutions of the EU—we have to act in a way that secures Hungarian interests, which are in fact the common interests of all the ‘co-owners’ and the entire ‘building’—with the aim of ensuring that this should be a nice place for everyone to live.

What can we do concretely to exercise our co-responsibility for EU democracy? First, we can monitor the functioning of democracy in European institutions with at least the same degree of scrutiny as we apply to our domestic institutions, that we also draw attention to the signs of decay in EU democracy, and that we develop proposals to eliminate emerging operational disorders. One of the most visible manifestations of this responsibility came in regard to the decision of the Hungarian Parliament, which was passed by parliamentarians in July 2022, regarding the position to be taken in relation to the future of the EU.1 The then recently elected parliamentary majority instructed the government to point out first the malfunctioning of European institutions, i.e. their democratic deficit, and also their misguided decisions. In addition to these criticisms, the Parliament also supplied guidelines on how to solve the problems that have arisen.

At the heart of the conclusions of the parliamentary resolution lies the constitutional structure of the EU, the so-called Treaty of Lisbon signed in 2007, which states that one of the foundations of EU policy is the creation of an ‘ever closer union’. The problems that arise in regard to this exemplify how a nation’s democracy—or in this case the democracy of EU institutions—wears out over time. The parliamentary decision criticizes the wording used in the Treaty of Lisbon as problematic because the Brussels institutions are trying to take powers from the member states by referring to this passage, despite the fact that the rest of the Treaty does not provide any legal basis for this. They do this despite the fact that ‘ever closer union’, in the context of the text in which it appears, clearly does not refer to centralization in Brussels. The exact wording of the treaty reads as follows: ‘to continue the process of creating an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe, in which decisions are taken as closely as possible to the citizen in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity.’2

This sentence is not about the sphere of competence of EU institutions, but about decisions being made at the level at which they are most effective, and specifically at the closest possible level to the citizens (we could say: ‘lowest possible level’). Ad absurdum, this could even be taken to mean that some EU competences might be made national competences again, if need be. However, Brussels institutions started to employ this wording as a loophole. In the Hungarian view, this is wrong. It is a problem because it does not strengthen but rather weakens the unity of the peoples who make up the EU. It diminishes rather than increases trust in common institutions. It makes the operation of the Union more difficult, not more efficient. This loophole must therefore be closed—preferably by deleting the wording that has given rise to abuses.

‘We are merely pointing out that certain elements within the regulation provide an opportunity for anti-democratic abuses, and must be eliminated in order for democracy to function properly’

However, it is important to see that the decision is not aimed at eliminating the concept of EU powers, nor is it even intended to weaken them. The best example of this is that when it comes to developing military capabilities, the Hungarian parliamentary resolution specifically calls on the government to advocate for expanded EU powers, and a rather radical expansion at that: ‘a joint European army must be set up, as a guarantor of European security.’3 For a number of member states that want to retain military security as a national competence, this is almost a red line in terms of the possible expansion of the powers of the Union. Why am I highlighting the example of defence policy? Because it shows particularly clearly that the Hungarian position does not equate strengthening European democracy with dismantling EU powers. Despite the various abuses in Brussels, Hungary continues to insist that the process of European integration should be based on a duality of national and community powers: the division of powers between the two levels can be democratic. We are not even suggesting that the regulation currently in force is inherently anti-democratic. We are merely pointing out that certain elements within the regulation provide an opportunity for anti-democratic abuses, and must be eliminated in order for democracy to function properly.

The concept of the rule of law often comes up in the mutual criticism of the European institutions and Hungary. In essence, the rule of law means nothing more or less than what is prescribed in legitimately adopted legislation must be adhered to—in the case of the EU, the Treaty and resultant regulations. If the Community institutions act in direct contradiction to the text of the Treaty or the original legislative intent underlying it, then the principle of the rule of law set forth in the Treaty has been violated. Of course, it is relatively difficult to prove legislative intent with certainty. However, if doubts arise as to whether the current text is in line with the original legislative intent, the solution is not to violate the text of the law, but to change it within the bounds of the Treaty. This is the most crucial element in Hungarian criticisms of Brussels, in the Budapest–Brussels debate regarding the state of democracy. Nor is military security the only issue on which the Hungarian side would like to see the communal character of the EU strengthened. The guidelines issued to the government by the Hungarian Parliament also include the recommendation that certain rights should be raised to the level of EU law. For example, this should include the right of every nation to decide who they do and no not wish to live alongside in their own country. (By definition, this does not refer to the free movement of EU citizens within the EU, but rather of accepting migration from outside the EU.)

In the same way, the Parliament wishes to strengthen EU law in the field of national minority protection. This is a typical example of a case in which subsidiarity does not mean the ‘downward’ but rather the ‘upward’ delegation of powers. Since minority rights often have to be protected against actions conducted by the state in which they live, it is a core value of the EU, in terms of enforcing the ‘rights of persons belonging to minorities’, that the level above the nation state is also given powers to ensure compliance in cases where this cannot be done at the member-state level. However, there are also elements of the Hungarian position that aim to limit the competences of Brussels institutions. For example, we want to prohibit EU institutions from taking out loans to be repaid, directly or indirectly, by the citizens of all member states. This is a very important democratic principle: it is not legitimate to impose future financial burdens on any member state that its citizens have not agreed to undertake.

What Does the Parliamentary Resolution Mean?

First of all, the parliamentary resolution means that the government’s hands are tied in the European political arena for this election cycle. It cannot agree to something with the other member states that contradicts this parliamentary resolution. If the government nevertheless wishes to agree to something contrary to these guidelines, because it is seen as unavoidable, then it must first consult with Parliament. There are procedures for this: if necessary, Parliament can amend its own decision, as was the case, if not formally, then at least in a practical sense, in the case of Sweden’s NATO accession. On the other hand, it does not mean that we can assume that the government has already achieved everything entrusted to it in the resolution. It must be acknowledged that the legal system of the EU currently contains loopholes that leave opportunities for abuse. Until they are closed, we must draw attention to the precise current text of the Treaty and the original intentions of the legislators who drafted it. We must assert our related and other interests within the framework of the current legal system of the EU.

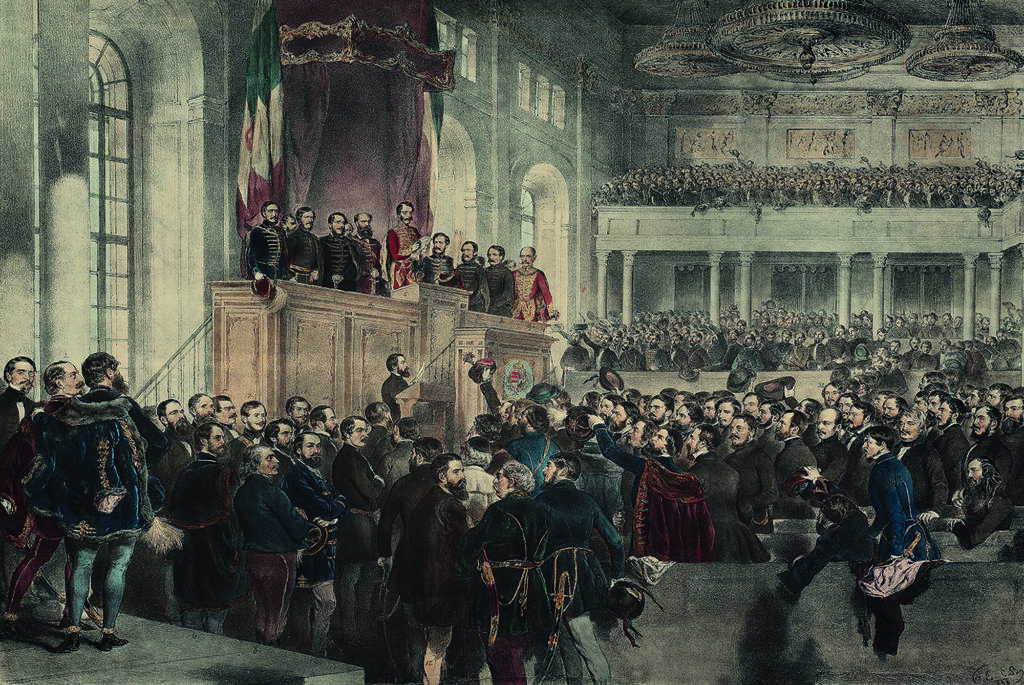

Hungary has form in this. Indeed, Hungarian history is full of constitutional revolutions—periods when, acting within the framework of the old (obsolete or inherently flawed) constitutional order, we created something radically different from it: a new, better, more democratic constitutional order. In this regard, we could even go back to the Golden Bull, which established Hungarian noble democracy in 1222, unquestionably a very long time ago. Just as the memory of the constitutional revolution that settled the relationship between Hungary and the Habsburg Empire exactly 500 years after the Golden Bull, in 1722, under the name Pragmatica Sanctio (the Pragmatic Sanction), lives on relatively dimly in the public memory. On the other hand, the memory of the April Laws that created modern Hungarian civic society in 1848 are among the most fundamental components of modern Hungarian national consciousness.4 The 1956 Revolution also sought a constitutional transformation, but was bloodily put down by Soviet invaders before the constitutional changes were completed. However, we were more fortunate when it came to the constitutional changes of the late twentieth century. After the events of 1989, we at first patched up the old, communist constitution, acting within its framework. Finally, we adopted a completely new constitution in 2010, but did not achieve this in a revolutionary way either. Instead, it was passed without any transgression of the old constitution, which had already been substantially transformed into a democratic document. We Hungarians act in accordance with our own constitutional revolutionary traditions to stop and reverse the decay afflicting democracy in the EU. Within the existing legal framework, we voice our critical insights and initiate changes that may seem brave or far-reaching. However, we cannot forego clearly naming the problems and formulating the desired changes because our responsibility as ‘co-owners’ obliges us to do so.

In 2022, there were two proximate reasons for the adoption of the parliamentary resolution. One was that it was preceded by the series of conferences organized by the EU on the future of European integration, in which the Hungarian population showed a relatively high interest and in which it participated to a degree far exceeding the EU average. Parliament saw that such a resolution would oblige the government to respect the results of the Hungarian consultations, even if otherwise the EU initiative did not entail such a formal obligation. What is certain is that Hungarian legislators saw fit to make the position of the Hungarian participants in the social debate a formal obligation for their own government. There is little doubt that the government would have taken the results of the conferences into account regardless, but the endorsement of their outcome by Parliament both solidified the government’s European policy and gave it even greater legitimacy. Here, the difference in emphasis between the understanding of democracy in the Brussels institutions and the Budapest Parliament is clearly visible. Although there is a similarity in that both the EU and Hungarian capitals saw it as vital to gather information about public opinion (I encourage everyone to notice such similarities, in addition to being aware of the differences!), some differences also emerged. For EU institutional leaders, the conference series served as a means of orientation: how much tailwind could they expect for their plans, and how much resistance would they generate if they sought to carry them through? On the Hungarian side, by contrast, we saw that once the people had been consulted, the opinion they expressed was seen as binding upon the political elite they had elected.

‘If a healthy ratio between conceptual and procedural debates prevailed and emotionally overheated reasoning were supplanted by rational positions in both areas, then the exchanges of opinions—and even clashes of opinion—would almost certainly be more productive than they are today’

Another piece of historical context behind the parliamentary decision was the sanctions intended to punish and halt Russian aggression against Ukraine. According to the Hungarian assessment, the main problem with these was and remains that instead of punishing the aggressor, it is rather the EU, which stands for Ukrainian sovereignty and territorial integrity, that is put at a disadvantage, together with its member states. In this way, not only do sanctions not deter Russia from aggression, they specifically encourage it to continue, i.e. they achieve a result that is directly contrary to their goal. Moreover, we have to finance this joint mistake of the EU and Ukraine. One may ask whether it was expedient to link the two separate issues in this parliamentary document: the problems of democracy in community institutions and the—at the time merely assumed—counterproductiveness of sanctions. Would it not have been more appropriate to make two separate decisions? The link between the two topics was that, in the tense situation of that time, we saw it as particularly important to keep the toolkit for representing the Hungarian position within the framework of EU democracy and the rule of law (which, as I outlined above, functions more and more poorly, but still exists). We therefore obliged the government to use all the opportunities provided by current EU legislation to enforce Hungarian interests with regard to sanctions, but in no way to go beyond them. Here too we can say with confidence that the government would certainly have acted accordingly even without a parliamentary decision, since Hungarian political culture affects the government just as much as it does Parliament. Supported by the resolution of the Parliament, however, the government’s actions are not only supported by EU law, but also enjoy domestic political legitimacy.

This is the story behind the Janus-like character of Hungary’s sanctions policy, which is relatively difficult for outsiders to understand, but very easy to understand based on the Hungarian rule-of-law approach. In essence, it means that the government seizes every possible opportunity to draw attention to the counterproductive nature of sanctions, and even goes to the extreme (as it is somewhat misleadingly put) of raising the prospect of employing its veto, or at times even using it, in order to eliminate elements in the sanctions that run counter to existential Hungarian interests. However, when a decision is made on a sanctions package on the basis of a negotiated agreement, the Hungarian authorities—in contrast to the authorities of some countries that are outwardly much more pro-sanctions—implement it properly. The ineffective and counterproductive nature of the sanctions, which could only be predicted based on preliminary calculations when the Hungarian parliamentary decision was adopted, can now be measured precisely. Politics often finds itself in a situation similar to that faced with regard to sanctions in the summer of 2022: the expected impact of political decisions has to be estimated in advance. Since the future can only be forecasted, never known with any certainty, it is natural that both conceptual debates and conflicts of interest will come to the fore during discussions on such matters.

The relationship between Hungary and the EU institutions would be healthy if it were predominantly characterized by such conceptual debates—especially if both parties employed strictly professional arguments and, as far as possible, refrained from displays of emotion. This could be supplemented by discussions on the practical application of common values such as democracy, the rule of law, human rights, etc. at the EU and national level—during which, ideally, both parties would express their opinions while staying strictly within their respective competencies. I am not advocating a reversal of the proportion of conceptual and procedural debates. If a healthy ratio between conceptual and procedural debates prevailed and emotionally overheated reasoning were supplanted by rational positions in both areas, then the exchanges of opinions—and even clashes of opinion—would almost certainly be more productive than they are today. This is one of the important opportunities for the new institutional cycle currently approaching within the EU.

Translated by Thomas Sneddon

NOTES

1 ‘Decision of the Hungarian Parliament 32/2022. (VII. 19.) OGY.’ – ‘Az Európai Unió jövőjével kapcsolatosan képviselendő magyar álláspontról’ (On the Hungarian Position to Be Represented Regarding the Future of the European Union), https://jogkodex.hu/doc/3464819.

2 ‘Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union— Consolidated version of the Treaty on European Union—Protocols—Declarations annexed to the Final Act of the Intergovernmental Conference which adopted the Treaty of Lisbon, 13 December 2007’, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX%3A12012M%2FTXT.

3 ‘Decision of the Hungarian Parliament 32/2022. (VII. 19.) OGY’.

4 Ferenc Mádl Institute, ‘175 Years of the April Laws: Fundamental Legal Transformations in 1848 and as a Consequence of the Springtime of Nations, 3 April 2023’, https://mfi.gov.hu/en/175-years-of-the-april-laws-fundamental-legal-transformations-in-1848-and-as-a-consequence-of-the-springtime-of-nations/.