This article was published in Vol. 3 No. 2 of the print edition.

In 2010, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán declared that ‘Hungary sails in Western waters, but the wind blows from the East’. This phrase encapsulates Hungary’s continuing geopolitical destiny of being a country straddling the border of the eastern and western halves of Europe, both geographically and culturally. ‘Hungarians’, as Orbán said in a speech given in Beijing in 2017, ‘had moved to their homeland in the West from the East’.1 While such a position has often put this nation at the mercy of larger powers through history, from the Habsburg Empire to the Soviet Union, since the end of the Cold War era it has been attempting to turn this position to its advantage. In his address in Beijing, at the first meeting of the Leaders’ Roundtable Summit, Orbán declared that ‘our [Hungarian] gene pool has also always made us interested in the question of how to replace confrontation between East and West with cooperation.2 Orbán’s phrase characterizes a key foreign policy initiative that has been the subject of much debate in Europe: the Eastern Opening Policy.

As explained by Gergely Salát, sinologist and professor at Pázmány Péter Catholic University in Budapest, the policy has been touted as both a roadmap to economic growth and a strategy for diversifying Hungary’s foreign partnerships away from over-reliance on Europe and the US.3 One of the most visible manifestations of this policy has been the development of Hungary’s cyber infrastructure, the success of which is due in no small measure to the investments made by East Asian nations such as China, Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. Telecommunication towers and artificial intelligence (AI) research centres built by Huawei are what have captured most headlines around the world,4 but there have been advances made by others. SK On, a South Korean company, is producing lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles. Japanese and Taiwanese corporations intend to test autonomous vehicles at the newly constructed ZalaZONE test track in Zalaegerszeg.5 All demonstrate the potential East Asia sees in Hungary.

These investments have manifested in three notable Hungarian sectors: energy, logistics and transportation, and manufacturing. The advancement of these three sectors has positioned the nation as a hub for technology and logistics in the region, establishing it as a ‘middle power’ of influence, as Carlos Roa argues.6 The role that East Asian investment has played is two-fold: the first is the direct investment of capital into the nation, increasing employment in technology-related positions, increasing production, and giving it increased gravitas as a centre of research and development in the Central and Eastern European region. The second factor is the kind of relationships that Hungary has developed with Eastern powers, including those that are confrontational with the West, such as China. The Eastern Opening Policy has been part of an effort to balance Budapest’s relations with the EU and the United States as well as China. This paper will explore motivations, history, and sectors focused on Hungary’s Eastern Opening Policy.

The History of Hungary’s Eastern Policy

Trade relations with Eastern nations did not begin with the Eastern Opening Policy. Since the opening up of Hungary after the fall of communism in 1989, incentivizing foreign investment has been a key economic priority for the Hungarian government. Efforts to extend trade and diplomatic reach were pushed in earnest by successive Socialist administrations, starting under the direction of former Prime Minister Péter Medgyessy7 and continuing under Ferenc Gyurcsány.8 As Réka Koleszár explains, their efforts aimed to ‘boost cooperation from business to culture to academia’.9 From the inception of post-Soviet Hungary, East Asian relations have been oriented towards trade as well as knowledge and information exchange. With the opening up of the Hungarian economy, foreign direct investment (FDI) began to flow in from Taiwan, China, and India, and was widely distributed over a diverse range of sectors including finance, retail, mining, and those that this article focuses on: automotive manufacturing and logistics. Initially, such investments were not large, with that from China only amounting to $537 million between 1982 and 1991, rising to $2.7 billion between 1992 and 1999.10 Hungary and the rest of Central Europe offered three key advantages that China and other East Asian countries desired. First, and most importantly, was the matter of market access. With a position in Hungary, European markets would be more accessible, both in terms of geography and diplomacy.11 With a position in one European country, the others would become easier to reach. The second advantage was a skilled workforce. The manufacturing sector particularly stands to benefit from the established Hungarian workforce in sectors of interest to investors, including automotive manufacturing and electronics.12 The third factor was the cost of doing business. Both labour costs and taxes were low in Hungary. Although recently Hungary has signalled that it intends to adopt a global corporate tax along with the rest of Europe and the United States, the costs of doing business in terms of labour are still comparatively low. These advantages have endured to the present day, with international corporations taking advance of the welcome Budapest’s business policies have laid out, and using the nation as a staging point for their ambitions throughout Europe.

After Hungary’s liberation from communist rule, in contrast to his administration’s current supportive disposition towards Chinese relations, Viktor Orbán voiced caution regarding the growing ties between Budapest and Beijing fostered by Medgyessy. Koleszár describes Orbán’s first term as prime minister from 1998 to 2002 as ‘hawkish’ when it came to Chinese relations, with concerns voiced about Western values being protected, and seeing China’s investments as a possible Trojan horse infiltrating Europe.13 Today, such concerns are still voiced, but this time against Viktor Orbán instead of by him. Antonia Colibasanu encapsulates the views of those opposing closer Budapest–Beijing relations by describing them as ‘China’s backdoor into Europe’.14 As she further details, the relationship gives Orbán a counterweight against the EU when Budapest seeks to defy directives or agendas passed down from Brussels. The recent case of the EU’s withholding of funds from Hungary over accusations from Brussels of ‘failing to protect LGBTQ rights’ or to ‘protect the rule-of-law’15 has led Orbán to claim he is ‘seeking funding from other partners’16 to offset losses and rebalance Hungary’s international relations.

Hungary’s Ambitions

The concept that ‘geography is destiny’ is very pertinent in Hungary’s case. The aptness of Roa’s characterization of Hungary as a ‘keystone state’ can be seen when one considers its position in Central Europe at the intersection of the West Balkans, the western and eastern regions of Europe, and at the southern edge of the Visegrád Group of nations which extend to the Baltic Sea. Hungarian lands have a long history of being a meeting point—and often a violent one—between the great powers of the region. That status has been further solidified in the present day with China’s increasing presence in Central Europe. Today, Hungary maintains a balance in its relations with its Eastern and Western partners as a mechanism for its own development and autonomy from the influence and ambitions of bigger powers, using those larger ambitions to its own benefit by positioning itself as the meeting point and bridge between them.

A primary political goal for Hungary since the fall of the Iron Curtain has been to maintain its autonomy and freedom from foreign control and influence. The diversification of its international relations and trade has been a key strategy in maintaining and enhancing the autonomy pursued by the Orbán administration through furthering Medgyessy’s China policy and continuing its promotion throughout East Asia under the banner of the Eastern Opening Policy. As explained by Ágnes Szunomár, an expert in Chinese–Hungarian relations at Corvinus University of Budapest, ‘Hungary is attempting to avoid being too dependent on any one party, especially since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. It’s trying to reduce the very significant—over 80–85%—economic dependence on the West’.17 Beginning in the early 2000s, newly independent Hungary pursued connections with China primarily to further economic development. Orbán’s pursuit of such relations as a political counterweight to Western influence has been more pronounced since the inception of the Eastern Opening Policy. Development of its cyber-augmented logistical infrastructure in partnership with China would give Hungary greater influence over supply lines connected to China by virtue of its geographical position as a logistics node for rail lines, as well as its relationship to China. With Beijing’s currently troubled relations with other European nations, which retain a degree of suspicion as to Beijing’s intentions, such a geopolitical position would afford Hungary a level of autonomy from foreign influence due to its status as a link, both diplomatically and logistically. It could keep greater powers at arm’s length by being their connecting point.

‘Budapest is positioned as a critical link between East and West, both in terms of physical infrastructure and as a point of negotiation between nations’

The establishment of the Eastern Opening Policy in 2012 provided a clear structure regarding Hungarian objectives for its relations to the East. As Völgyi and Lukács detail, the Eastern Opening Policy identifies six key objectives:18

- The diversification of the geographical structure of exports.

- The diversification of the product structure of exports.

- The encouragement of foreign direct investment.

- The support of exports and the supplying activity of small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

- Economic cooperation in the Carpathian Basin.

- The institutional development of economic diplomacy.

The development of Hungary’s technology sector with regards to logistical and transportation infrastructure, and the telecommunications that connect it, impacts each of these objectives. Companies outside the traditional Western business sphere are attracted to an environment with European and American institutions and companies, offering further incentives to counties and companies east of Europe to invest in Hungary. The objectives outlined above, combined with Hungary’s previous history of technology and manufacturing development, have resulted in the country’s current growth in logistics, research and development, and manufacturing.

The Eastern Opening Policy is the result of the Hungarian approach to foreign affairs, which is to combine it with economic affairs. As explained by Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade Péter Szijjártó, both economic and foreign affairs were combined in conducting international affairs for Hungary, orienting relations towards improving the Hungarian economy.19 He outlined the approach as follows: ‘The main function is to help Hungarian companies be successful in external markets and to attract the best possible investments to Hungary. All government policies, including foreign policy, must serve the goal of making available more and more prestigious jobs for the Hungarian people.’ Szijjártó points to the decline of unemployment in the country from 12.5 to 3.5 per cent as an example of the policy’s success.20 Contrasting analysis and viewpoints have been developed, with one of the most notable being the Washington-based Center for European Policy Analysis, which criticizes the efficacy of the policy, citing examples such as the Budapest–Belgrade railway on account of its questionable economic utility and opaque organization, with its classified status extending for ten years. Patel Paszak also takes into account the statistical reality of Chinese investment, which comprises approximately 1.5 per cent of Hungarian exports and 6.15 per cent of imports—paltry numbers if China is to be considered an alternative to Western economic relations.21

Chinese efforts to develop relations in Europe were focused onto the initiative known as ‘17+1’ which included other European nations, with China being the plus one. Unfortunately for China, however, increased tensions and European suspicion of Chinese intent has resulted in a decline of the forum, with Lithuania the first to depart on account of its ‘divisive nature’.22 The other members subsequently turned away from what they regarded as a ‘plethora of unfulfilled promises and projects’.23 This has resulted in Hungary remaining the only EU member state still seeking to do business with China in earnest. In addition, the United States has pulled many nations away from China’s influence through agreements on technology security and warnings of cyber espionage and influence, leading to a shunning of China’s overtures by almost all of Europe, with the exception of Hungary, which has a history of trade and cooperation with China. This makes Hungary the only viable option to function as a staging point for China’s wider European ambitions. The result is its near monopoly on China’s Europe-based projects concerning cyber infrastructure, as well as logistics nodes with the potential to reach out to the rest of the continent. As such, Budapest is positioned as a critical link between East and West, both in terms of physical infrastructure and as a point of negotiation between nations.

Digitalization

The concept of ‘digitalization’, at least as it concerns infrastructure, is modernization through 5G telecommunications connections to enable increased efficiency and connectivity to a larger network of systems. Such an upgrade has been taking place in Hungary in part due to investments made in its IT, logistics, energy, and transportation systems through technological agreements with its East Asian partners, both in terms of research and development and production. The motivation for this trend is twofold: to maintain a competitive edge through increased efficiency and to combat the issue of rising labour costs and the resultant effect on companies. Coupled with the rise in general inflation due to rising petrol prices and an ongoing recession, many businesses have sought to cut costs by reducing employment levels. Automation, or digitalization, has been considered a potential solution in the face of rising costs.

Hungary’s development and implementation of artificial intelligence has been a key element in that automation. The Ministry for Innovation and Technology and the Artificial Intelligence Coalition detail the nation’s roadmap for implementing AI into the nation’s economic architecture in a ten-year framework called ‘Hungary’s Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2020–2030’. The strategy is sector-focused, with manufacturing, transportation, logistics, and energy production considered as the primary aspects. East Asian investments are involved in the first three. The necessity of artificial intelligence, as detailed in Hungary’s strategy, primarily concerns the automation of functions, increased economic benefit through better efficiency, and maintaining competitiveness in a changing global market and society. The strategy highlights forecasts claiming that an AI adoption rate of 11.5 per cent in ‘Southern Europe’, which includes Hungary, will result in a 6.6-billion-forint (approximately $18 million) boost to the region’s GDP. As for increased productivity, the strategy also hypothesizes that ‘data-driven’ jobs will increase human creativity and productivity, ‘enhancing the productivity, further added value and export capacity of Hungarian enterprises’.24 Both motivations point to the value of Hungary integrating its international relations into digitalization efforts. Infrastructure constructed with international powers will ensure continuity for global trade and logistics efforts. China’s Belt and Road Initiative has been specifically oriented towards providing common operating platforms, both physical and digital, around the world for the sake of efficiency and continuity.

Logistics and Transportation Development

When it comes to the nation’s geography, Hungary would not normally be considered a first choice for logistics operations. For one thing it is landlocked, which precludes all international maritime shipping. However, a combination of factors has worked to Hungary’s advantage to make it a desirable location as a logistics hub for the Central and Eastern European region.25 The primary manifestation of Hungary’s development in logistics has been its railway systems, for which the most consequential factor has been its relationship with China. While China has attempted to develop relations with other Central and Eastern European nations, as demonstrated through the ‘17+1’ platform, Hungary has been one of the few to maintain a cordial relationship with Beijing, as most of the region has kept China at political arm’s length.26 This political dimension positions Hungary as the primary recipient of Chinese infrastructural investments. Along with its international relations, Hungary’s geography comprises its second main advantage as a logistical hub. The nation’s position in the centre of the continent, bordered by eight other countries and with functional highway and rail lines connecting all of them, is a prime asset for Hungary in terms of logistics. The development of rail lines offers access beyond just the immediate nations bordering Hungary and further on to the rest of Europe’s freight rail network and to seaports such as Greece’s Piraeus port, which has also seen development from the Belt and Road Initiative.27 The Chinese Belt and Road Initiative has been a cornerstone of the Chinese–Hungarian relationship, as shown by examples such as the East West Gate (EWG) logistics terminal in Fényeslitke and the Budapest–Belgrade Railway project.28 Both have been designed with digitalization capabilities at their core, including AI capabilities and 5G connection, thereby improving efficiency and interconnectivity.

‘The necessity of artificial intelligence […] primarily concerns the automation of functions, increased economic benefit through better efficiency, and maintaining competitiveness in a changing global market and society’

Manufacturing

Hungary has a long history as an industrial nation, most notably, since the Cold War era, in automotive manufacturing and assembly. This history continues to the present day, in the form of electric vehicle manufacturing. With the rise in electric vehicle development and research into self-driving technology, Hungary has become a nerve-centre for future automotive testing and associated technology. Battery production, vehicle assembly, and other related transportation-focused manufacturing have all seen growth and modernization in Hungary, with investment from East Asian nations. Global brands such as BMW, Hyundai, China’s BYD, and Mercedes have all established vehicle assembly plants in Hungary, or are considering plans to do so, as have battery manufacturers such as China-based Nio and South Korea’s Samsung SDI. Electric buses have also found a base in Hungary to develop and begin implementation, with the Chinese firm BYD producing up to 1,000 electric buses this year at its newly automated assembly plant, up from 200 per annum.29

This rise in manufacturing is accompanied by testing and research facilities. In Hungary, the ZalaZONE Park has been a major attraction in the Central and Eastern European region for manufacturers in terms of testing electrical vehicles with self-driving capabilities. Beyond personal vehicles, a recent newcomer to Hungary’s manufacturing base has been German firm Rheinmetall, which has built a manufacturing plant for the Lynx military fighting vehicle in the ZalaZONE Park.30 Rheinmetall also makes use of the park’s self-driving test track, exploring remote control capabilities for the Lynx. The continued concentration of electric, self-driving R&D in the region, coupled with manufacturing, is likely to increase in the coming years, due to the concentration of both infrastructure and knowledge, while the developing logistics driving R&D in the region, coupled with manufacturing, is likely to increase in the coming years due to both the concentration of infrastructure and knowledge as well as the developing logistics infrastructure to distribute finished products.

The European Market

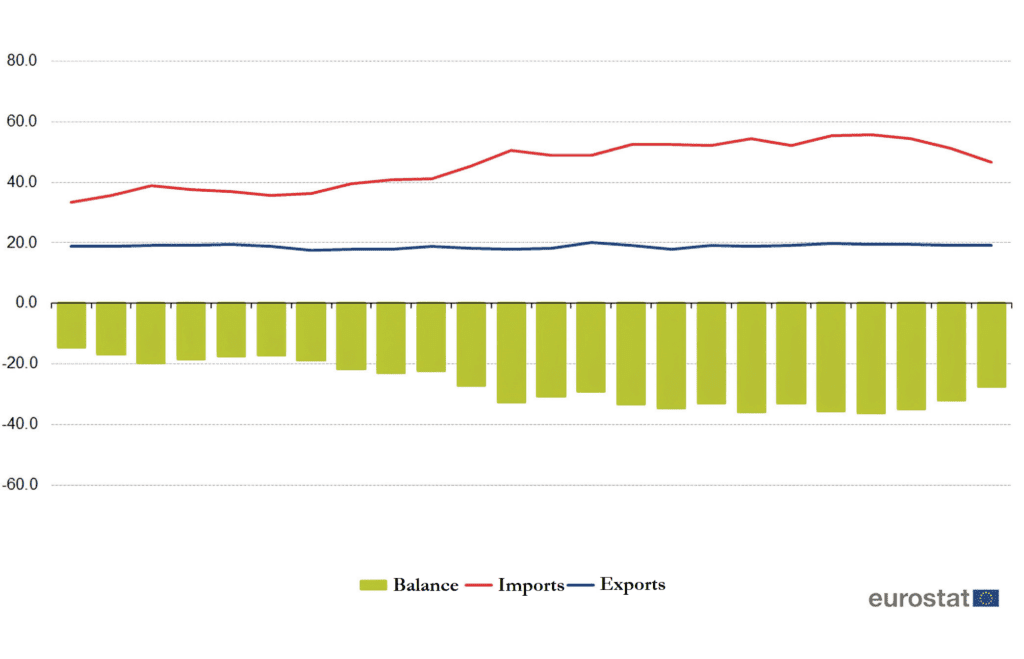

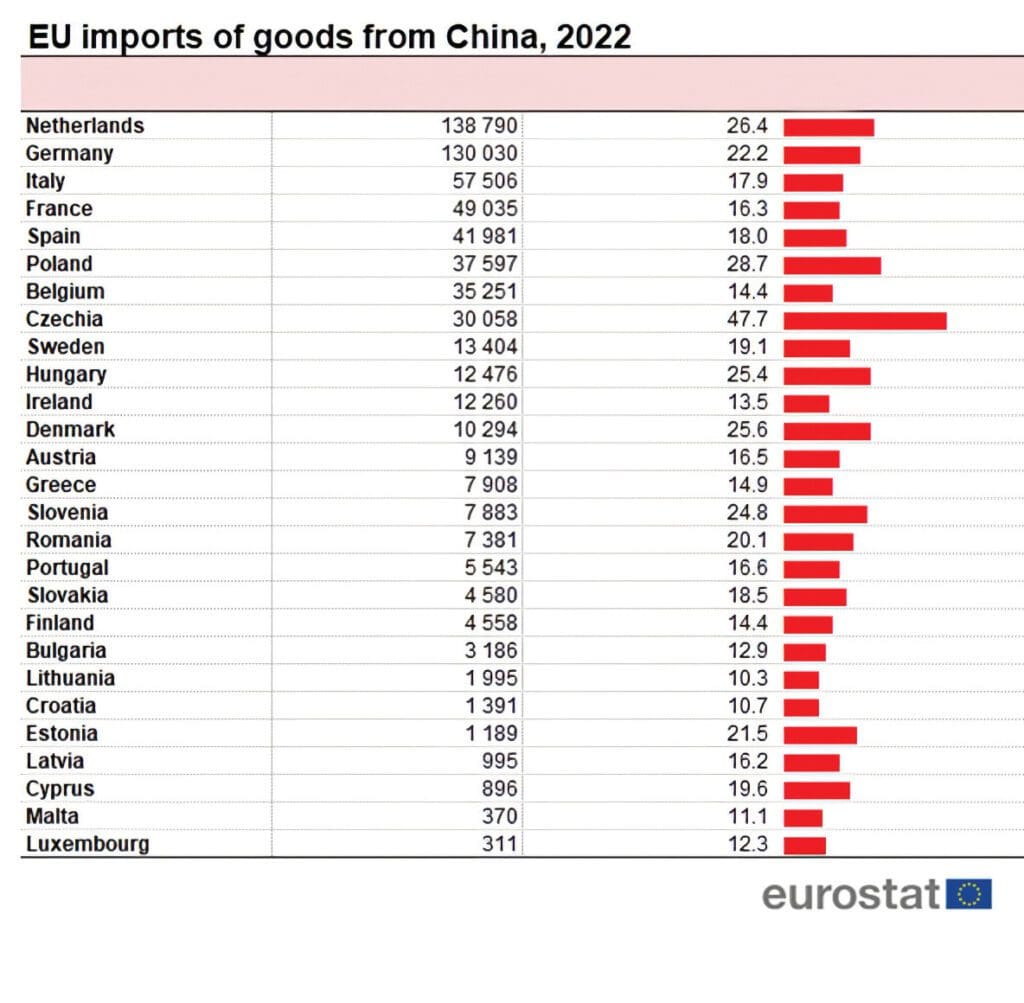

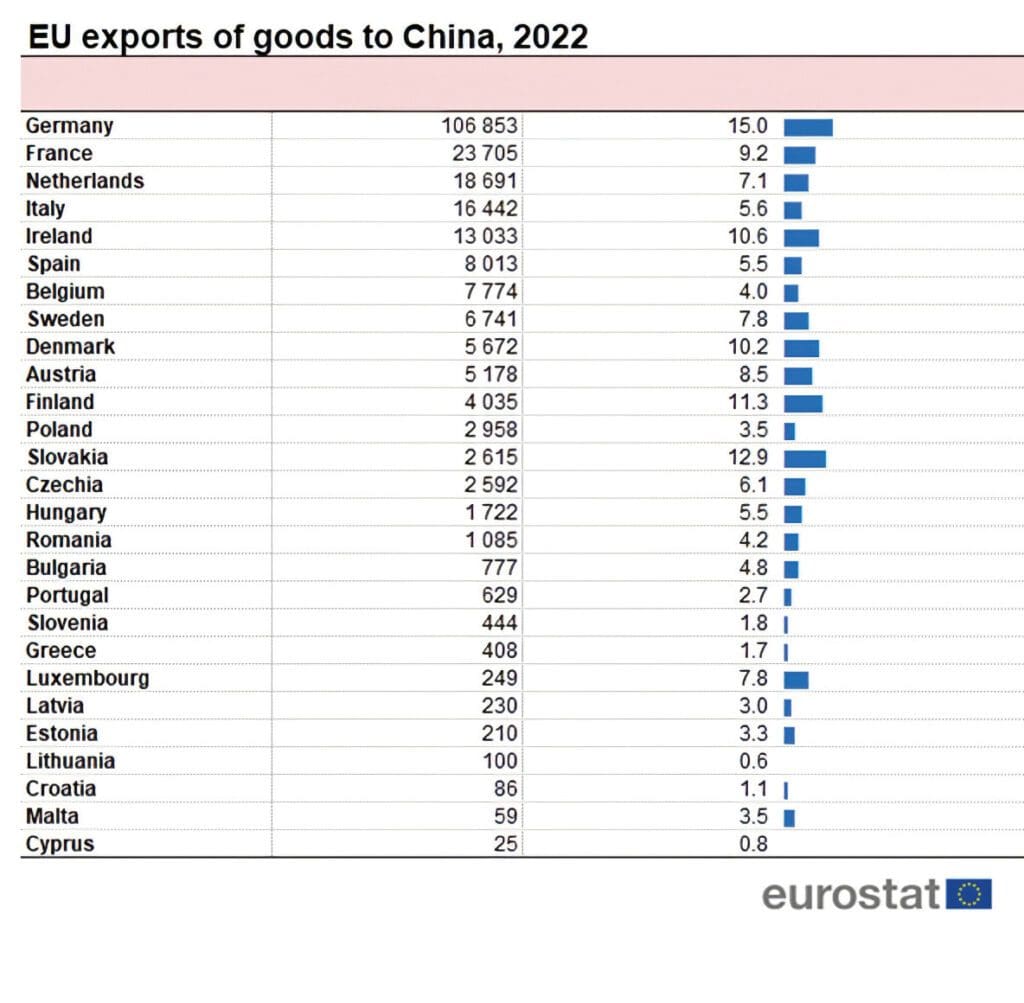

Besides Hungary’s own economy, utilization of Hungary’s geography by China as a gateway to Europe impacts the economies of the continent’s other nations. As mentioned earlier, Hungary’s unique disposition towards China allows it to act as a port for the rest of the continent. While political ties between Beijing and Europe’s various capitals have cooled in the past few years, economic ties have continued. As detailed by Eurostat, the EU saw its exports to China remain consistent, while imports actually increased between 2021 and 2022. The primary point of contention between Europe and China has been the sale of cyber-related technology. However, China still remains a primary source for many of Europe’s imports. In fact, as the two graphs below illustrate, the import–export relationship between the EU and China has become more unbalanced in 2022, with the EU taking in more goods than it sends to China. The continued reliance on China for imports is not a situation unique to Hungary but to all of Europe.

Trade deficits were common across Europe in 2022, according to Eurostat. What this unequal status demonstrates is that despite the deteriorating state of political relations between China and EU member states, Europe continues to be reliant upon China for goods, at least in the short to medium term. Such a market requires points of access into the continent and modern infrastructure to move goods, which is the role Hungary has established for itself. While Hungary’s own trade deficit with China is not unique in Europe, what does make its relations unique is the cyber infrastructure aspect. While most of Europe has turned away from Chinese cyber assets, partly due to an extensive US campaign,31 Hungary has continued to solicit such investments. While such a relationship between Budapest and Beijing has been met with scepticism and even hostility by the rest of the continent, such a relationship is likely to prove necessary for Europe’s continued facilitation of Chinese goods.

Conclusion

While the Eastern Opening Policy is not necessarily a new initiative or even a change in focus from Hungary’s initial post-Cold War trade relations with East Asian nations, the policy does entail a focus on investments. The focus on cyber-related infrastructure demonstrates a strategy of incorporating developing technology into critical national assets that will optimize autonomy in regional logistics and manufacturing. As the only European nation still seriously courting Chinese infrastructural investments, and having a geographic advantage stemming from its position in the centre of the continent, Hungary is situated to take full advantage of its status as a ‘middle power’ in the region.

NOTES

1 Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister, ‘Hungary Is an Ideal Pillar of the One Belt, One Road Initiative’, 1 May 2017, https://2015-2022.miniszterelnok.hu/hungary-is-an-ideal-pillar-of-the-one-belt-one-road-initiative/.

2 Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister, ‘Hungary Is an Ideal Pillar of the One Belt, One Road Initiative’.

3 Logan West’s interview with Gergely Salat, 24 November 2022.

4 ‘Huawei Establishes a New R&D Center in Budapest’, Hungarian Insider (21 October 2020), https:// hungarianinsider.com/huawei-establishes-a-new-rd-center-in-budapest-5618/.

5 Lin Chia-nan, ‘Taiwan, Hungary Form Tech Partnership’, Taipei Times (10 Jan 2022), www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2022/01/10/2003771083.

6 Carlos Roa, ‘Between East and West: The Prospect of Hungary as a Keystone State’, Hungarian Conservative (4 December 2022), www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/current/between-east-and-west-the-prospect-of-hungary-as-a-keystone-state/.

7 Ágnes Szunomár, ‘Blowing from the East’, International Issues & Slovak Foreign Policy, 24/3 (2015), 60–78.

8 Réka Koleszár, ‘Hungary–China Relations: Is It Time for a Change?’, China Observers (28 October 2022), https://chinaobservers.eu/hungary-china-relations-is-it-time-for-a-change/.

9 Koleszár, ‘Hungary–China Relations: Is It Time for a Change?’

10 Katalin Völgyi and Eszter Lukács, ‘Chinese and Indian FDI in Hungary and the Role of Eastern Opening Policy’, Asia Europe Journal, 19/2 (18 January 2021), 167–178.

11 Szunomár, ‘Blowing from the East’.

12 Völgyi and Lukács, ‘Chinese and Indian FDI in Hungary and the Role of Eastern Opening Policy’.

13 Koleszár, ‘Hungary–China Relations: Is It Time for a Change?’

14 Antonia Colibasanu, ‘Hungary, Poland, Serbia: China’s Backdoors to Europe’, Euractiv (1 September 2021), www.euractiv.com/section/china/opinion/hungary-poland-serbia-chinas-backdoors-to-europe/.

15 Marton Kasnyik, ‘EU Freezes Almost €22 Billion in Hungary Funds in Blow to Orbán’, Bloomberg (23 December 2022), www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-12-23/eu-freezes-almost-22-billion-in- hungary-funds-in-blow-to-orban.

16 ‘Hungary Needs EU Funds for Energy Investments, PM Orbán Says’, Reuters (26 September 2022), www.reuters.com/article/eu-hungary-orban-energy-idUKS8N2YF0FS.

17 Logan West’s interview with Ágnes Szunomár, 24 January 2023.

18 Völgyi and Lukács, ‘Chinese and Indian FDI in Hungary and the Role of Eastern Opening Policy’.

19 Mark Arend, ‘Eastern Europe: Foreign, Trade Policy Are One in Budapest’, Site Selection (March 2019), https://siteselection.com/issues/2019/mar/eastern-europe-foreign-trade-policy-are-one-in-budapest.cfm

20 Arend, ‘Eastern Europe: Foreign, Trade Policy Are One in Budapest’.

21 Patel Paszak, ‘Hungary’s “Opening to the East” Hasn’t Delivered’, CEPA (8 March 2021), https://cepa.org/article/hungarys-opening-to-the-east-hasnt-delivered/.

22 ‘Lithuania Quits “Divisive” China 17+1 Group’, Euractive (24 May 2021), www.euractiv.com/section/china/news/lithuania-quits-divisive-china-171-group/.

23 Andreea Brînză, ‘How China’s 17+1 Became a Zombie Mechanism’, The Diplomat (10 February 2021), https://thediplomat.com/2021/02/how-chinas-171-became-a-zombie-mechanism/.

24 Ministry of Innovation and Technology, ‘Hungary’s Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2020–2030’, May 2020, https://ai-hungary.com/files/e8/dd/e8dd79bd380a40c9890dd2fb01dd771b.pdf.

25 Ganyi Zhang, ‘Hungary, a Promising Logistics Hub for the China–Europe Connection’, Upply (22 June 2021), https://market-insights.upply.com/en/hungary-a-promising-logistics-hub-for-the-china-europe- connection.

26 Brînză, ‘How China’s 17+1 Became a Zombie Mechanism’.

27 Silvia Amaro, ‘China Bought Most of Greece’s Main Port and Now It Wants to Make It the Biggest in Europe’, CNBC (15 November 2019), www.cnbc.com/2019/11/15/china-wants-to-turn-greece-piraeus-port-into-europe-biggest.html.

28 Zhang, ‘Hungary, a Promising Logistics Hub for the China–Europe Connection’.

29 Patthy Gellar, ‘BYD Is Increasing the Capacity of Its Factory in Komárom Fivefold’ (Translated), Magyarbusz (26 November 2020), https://magyarbusz.info/2020/11/26/otszorosere-noveli-komaromi- gyaranak-kapacitasat-a-byd/.

30 Paolo Valpolini, ‘Rheinmetall Hands over First Lynx Infantry Fighting Vehicle to NATO Member Hungary’, EDR Magazine (17 October 2022), www.edrmagazine.eu/rheinmetall-hands-over-first-lynx-infantry-fighting-vehicle-to-nato-member-hungary.

31 Laurens Cerulus and Sarah Wheaton, ‘How Washington Chased Huawei out of Europe’, Politico (23 November 2022), www.politico.eu/article/us-china-huawei-europe-market/.

Related articles: