The political role of the European Commission is a subject of constant debate, generated by a difference of worldviews regarding the European Union as an entity. The fundamental difference of opinion between the two camps comes down to the depth of integration. A group of federalists demanding ‘more Europe’ and deeper integration is pitted against a group of sovereigntists who envision the future of Europe as being based on nation states and intergovernmental cooperation. The European Commission has a key role in this debate: it is the institution which could assume the role of a supranational government, since national considerations have the lowest priority in its operation.

Introduction

The depth of integration is indicated relatively accurately by the competencies of the European Commission. Martin Selmayr—the former influential general secretary of the Juncker Commission—is of the opinion that the Commission ‘has always been a body between technocracy and politics’. In his view, ‘since the beginning, there have been the federalists who wanted the Commission to turn into a European government and the sovereigntists, who wanted to keep the Commission as a technocratic organization. Many of the debates today go back to this tension.’1

When we subject the political role of the Commission to analysis, the first step is to define what we mean by ‘political role’ or ‘being politicized’. In the relevant analysis offered by Neill Nugent and Mark Rhinard, four possible interpretations of ‘political role’ are identified. The first is the political role in an ideological sense, the second is policymaking, the third is institutional, and the fourth is the administrative political role.2

Since the ideological role is usually assumed by elected institutions which have democratic legitimacy (parliaments), the latitude or discretion of a bureaucratic organization without such legitimacy seems to be the most important object of scrutiny in this respect. It is also evident that this issue has become the focus point of the debates between sovereigntists and federalists as well. In my view, different visions with respect to the depth of integration are also ideological in nature, thus it is crucial to examine this issue with regard to the Commission.

After all, the political role of the European Commission is always a matter of sovereignty from the member states’ perspective, and if we look back on the history of European integration, we can see that the sharpest conflicts and most intense political struggles regarding the future of the ‘European project’ have always taken place between the current president of the Commission— craving more extensive powers and more room for manoeuvre politically—and heads of governments of nation states strongly committed to sovereignty. It shall suffice to remind ourselves of the tensions between

Charles de Gaulle and Walter Hallstein, Margaret Thatcher and Jacques Delors, or even Jean-Claude Juncker and Viktor Orbán. In the light of the above, I shall provide an overview of the most influential Commission presidents’ interpretation of their political roles.

The History of the European Commission in a Nutshell: the Road to the Foundation of the European Commission

The story of the institution of the European Commission began many decades ago. It received its current name with the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009. At the dawn of European cooperation, the executive body of the ECSC (European Coal and Steel Community), established in 1951, was called the High Authority. Euratom, created by the Treaty of Rome (1957), also had its own Commission, similarly to the European Economic Community (EEC). It can be said of all of them that their operations were of a professional/executive nature initially, but that the organization and operation of the Commission began to shift, over time, towards increasingly political roles. With the Merger Treaty of 1965, the executive bodies of the ECSC, the EEC, and Euratom merged, thereby creating the Commission of the European Communities.3

During the period when three executive bodies were operating simultaneously, one of them, the High Authority with its nine members, took priority. Jean Monnet was unanimously elected its first president, and Luxembourg was selected as its seat. The High Authority was not supposed to ask for or accept advice from either governments or other organs, and ‘performed its work bearing the general interests of the community in mind, in complete independence’.4 The first president of the Commission of Euratom was Louis Armand, and the first president of the EEC Commission was Walter Hallstein. Hallstein’s role and his Commission’s understanding of its political role will be examined later when the tensions between him and Charles de Gaulle are analysed.

The Evolution of the Commission from the Merger of 1967

As a result of the Merger Treaty, which was signed in 1965 and entered into force in 1967, the Commission of the European Communities was established, with Jean Rey as its first president, but due to Hallstein’s strong political stance the latter is regarded by many as president of the first ‘modern’ Commission. The main tasks of the unified Commission were similar to the present Commission’s responsibilities: it was meant to represent the interests of the European Communities, irrespective of the interests of member states; it was already considered the ‘guardian of the treaties’; it proposed legislation; it was the executive body of the Community, representing it in the field of foreign relations.5 Therefore it can be safely stated that as early as 1967, the Commission of the European Committees already had most of the powers of its successor.

The main tasks of the unified Commission were similar to the present Commission’s responsibilities: it was meant to represent the interests of the European Communities

The Maastricht Treaty (1992) extended the Commission’s scope to the common foreign and security policy as well as to cooperation in justice and home affairs. The Treaty of Amsterdam (1997) maintained the Commission’s earlier competences; the modifications it introduced were aimed at enhancing the efficiency of the Commission’s operation. The Treaty of Nice (2001) enhanced the Commission president’s powers and modified the system of nomination of the president and members of the Commission.6

The Provisions of the Treaty of Lisbon on the European Commission

The Treaty of Lisbon, signed in 2007, established the European Commission in its current form and under its current name. The Commission is a supranational body representing the collective interests of the community, and its members are designated by the governments.

The fundamental responsibilities of the Commission remained unchanged: ‘[It] promotes the general interest of the EU by proposing and enforcing legislation as well as by implementing policies and the EU budget.’7

The Commission is an executive body, tasked with the implementation of the decisions made by the institutions of the community.8 ‘Union legislative acts may only be adopted on the basis of a Commission proposal, except where the Treaties provide otherwise.’9 ‘The Commission shall neither seek nor take instructions from any Government or other institution, body, office or entity.’10 As of 1 November 2014, ‘the Commission shall consist of a number of members, including its President and the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, corresponding to two thirds of the number of Member States, unless the European Council, acting unanimously, decides to alter this number’.11

Finally, regarding the current institutional framework, it should be noted that over the last twenty years, additional formal and institutional competencies have been granted to the president of the European Commission in various amendments to the treaties. As a result, the president has gained a much stronger influence in nominating commissioners, exerting political control over the Commission, determining the portfolio of commissioners, and deciding on the dismissal of commissioners.12 Regarding the position of the Commission president, a continuous tendency of strengthening can be observed.

The Political History of the European Commission

In our scrutiny of the European Commission’s understanding of its political role as the ‘government’ of the Union, we should return to the key question raised in the introduction: is the EU moving towards federation based on the US model from the very beginning—and is it predetermined that it should be doing so? Or, alternatively, is it also possible for it to continue to operate by relying on nation states?

When Selmayr, for instance, argues for the Commission’s assumption of a political role and for deeper integration, he quotes Jean Monnet, one of the founding fathers of the EU. In Selmayr’s view, Monnet was clear about the need for the High Authority to be a political actor when he said, ‘Cooperation between nations, however important it may be, does not solve anything. What one has to seek is a fusion of the interests of the European people, not merely to preserve a balance among those interests.’13

This statement does prove that federalism was already present in the very first moments of integration, together with the vision of a political Commission which would be inseparable from it and would have to formulate and enforce supranational interests. This concept raises serious concerns on the sovereigntist side. What democratic legitimacy does the Commission have for the formulation of such interests? By what means will it be possible to hold the Commission accountable for its political decisions? What ideological criteria will determine its course of action? After all, the ideological aspect has a role to play at parliamentary elections, and it is by following this chain of legitimization that the governments of nation states also implement their programmes which are formulated according to their own worldviews. But what would determine the ideological background of the Commission? This is one of the crucial issues in this respect, also serving as a basis for debate between sovereigntists and federalists.

It should be noted at this point that all bureaucratic organizations, as analyses have suggested, are target-oriented, and consequently have a sense of mission. The target and mission of the Commission is, clearly, to ‘breathe life into the central ideological project of integrating Europe’.14

The Beginnings: the 1960s and 70s

It is evident already from Monnet’s statement quoted above that the federalist interpretation of the Commission’s political role is a far from new one. There has been no major shift in views on how the Commission is defined as an institution. We should rather put it like this: the Commission’s political activism has continually been demanded, and the extent of this activism has always been subject to the current Commission president’s attitude, his charisma, and the strength of nation states as a counterweight.

A striking example of this controlling role of heads of sovereigntist nation states was offered in the 1960s by French president Charles de Gaulle (1959–1969). As the first president of the EEC Commission, Walter Hallstein (1958–1967) had a charismatic leader’s reputation; he became known for formulating the so-called Hallstein Doctrine15 in Konrad Adenauer’s cabinet before assuming an important role in European politics. He was a firm supporter of deepening integration, and he believed in its rapid implementation. It is no exaggeration to say that he—as Commission president—was the chief driver of integration during those decades. While he was in office, European legal harmonization was significantly accelerated. For him, a politically active Commission with strong powers had a special significance: he saw it as a guarantee for creating a united Europe.16

De Gaulle envisioned a form of integration which would strictly limit the transfer of sovereignty

In contrast, de Gaulle envisioned a form of integration which would strictly limit the transfer of sovereignty, and, in contrast to supranational ideas and concepts which were highly popular at the time, ensure a confederative European alliance on an intergovernmental basis.17 In the Fouchet Plan on the future of Europe (1961) proposed by de Gaulle, he called the political union ‘a Union of States built on respect for the personalities of its peoples and the member states’, which should have no power of coercion over them. The vision of the Union of States rejected the federalists’ scenario in which the member states of the Community ‘would lose their national personalities, and in the lack of a federative leader […] they would be governed by a homeless technocratic high tribunal, a body held accountable by no one’.18

This last quote clearly shows de Gaulle’s opinion of a European government incarnated by the Commission. It was no surprise that conflict was permanent between him and Hallstein, with the latter wishing to strengthen the Commission’s role. The climax of their wrangling was the ‘empty chair policy’ of 1965, when the sessions of the Council of Ministers were not attended by French ministers. One of the highly debated issues was the introduction of majority voting in the Council, which was regarded by France as a renunciation of member-state sovereignty. The debate escalated further, with de Gaulle criticizing Hallstein for having prepared his budgetary proposal without prior consultation with the member states, and for having acted like a head of state.19

De Gaulle provided an immediate response to Hallstein’s every federalist move, and to any action of the Commission whenever it assumed a central political role. The General was a committed confederalist, but even he could not avoid making compromises in the interest of European cooperation. Still, it can be stated that the fight was won by the president of a member state, and the Commission president was defeated. Qualified majority decision-making was adopted in a weakened form, combined with the actual right of veto, and the Commission was obliged to first present all of its initiatives to the Council before sharing them with the public.20

At the same time, de Gaulle’s victory also had an impact on events in the 1970s, as during this period the intergovernmental and democratic character of integration was becoming more pronounced, against the competencies of the supranational Commission. The European Council—which had been an informal forum of discussions between heads of state and the governments of the member states—was formally set up in 1974.21 Subsequently, in 1979, members of the European Parliament were elected directly for the first time, which also reinforced the nation-state foundations of the Union.22 In this period, European leaders took considerable steps towards intergovernmental but still meaningful cooperation between member states, calling for joint action on the global stage.23

The Delors Commission

From the perspective of the Commission’s political activism, one of its most successful periods was linked with Jacques Delors’s tenure as Commission president. While he was in office, European integration progressed rapidly, the common market became fully established, and the foundations for the common currency were laid. Delors is undoubtedly one of the greatest heroes of the federalists, while in the eyes of nation states’ supporters, particularly in Britain, he is not viewed positively (mainly due to his conflicts with Margaret Thatcher).

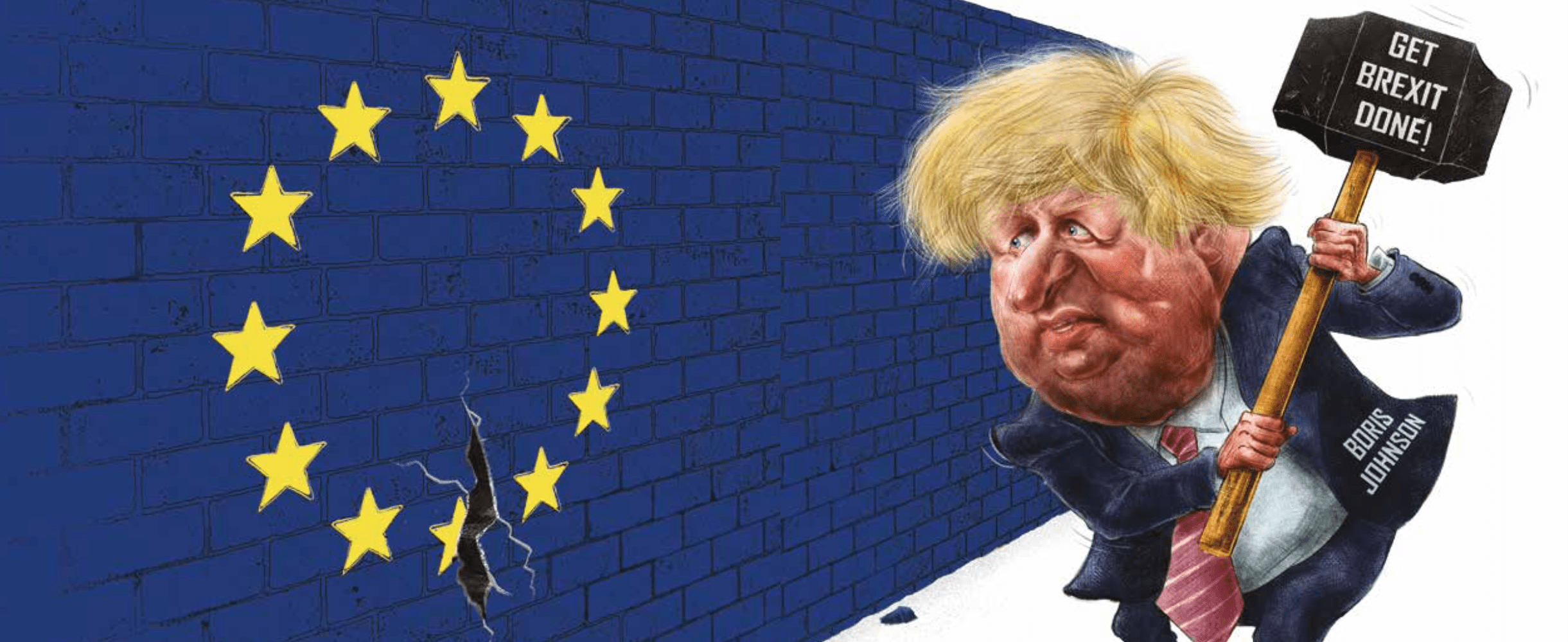

Jacques Delors initiated large-scale reforms, beginning in 1984. As for his legal efforts, his most important step was to lay the groundwork for the first systemic modification of the founding treaty, the Treaty of Rome.24 Prompted by its president, the Commission published a white paper in 1985 which enhanced the integration of the common market by passing hundreds of relevant pieces of EU legislation. The Single European Act, which included most of the proposals of the Delors Commission, was ratified in 1986. The specific plan to establish the Economic and Monetary Union was also formulated by the expert committee under Delors’s supervision (1988), publishing its report in 1989.25 Several member states were clearly opposed to the plan (most notably, the United Kingdom), and some analysts have claimed that the roots of Brexit are to be found in this conflict.26 The most significant event during his tenure was perhaps the adoption of the Maastricht Treaty, establishing the European Union as we currently know it, in 1992.

The bottom line is that Delors was a strongly federalist Commission president who felt it was his mission to lead Europe into a new era. In his own words, ‘my objective is that before the end of the millennium Europe should have a true federation. The Commission should become a political executive which can define essential common interests.’27 Moreover, he believed that ‘we must define the political Europe that we want. We must plead for the federal approach.’28

Considering the balance of the Delors presidency, it can be stated that the federative transformation of Europe remained incomplete: intergovernmental bodies and the European Parliament continued to have strong powers even after the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty. Although Delors seemed to consider his role as that of a head of state, this came from his character and not from any strengthening of the Commission’s powers. The balance of power within the European Union and the Commission continued to hover between federation and intergovernmental cooperation.

Santer and Prodi

Regarding Maastricht, the issue of political union made it necessary to raise the question again: should Europe proceed towards a federative future or towards intergovernmental cooperation between sovereign states? The member states were unable to come up with a uniform answer, and therefore a central definition of political union was still impossible to provide.29 The pillared structure of the Maastricht Treaty heralded a new era in the history of integration, ‘giving the green light to the implementation of supranational solutions in certain areas in line with various policies, and codifying intergovernmental decision-making at other points’.30 After several decades, the debate surrounding federation versus nation states remained undecided.

With regard to the period following Maastricht, the general statement can be made that the ratification of the treaty failed to answer a series of questions which were to prove crucial for the future of the Union. The founding treaties of the European Communities remained essentially unchanged for thirty years, surviving without substantial amendment. The first comprehensive modification was the Single European Act mentioned above, followed, with increasing frequency, by a series of amendments: Maastricht (1992), Amsterdam (1997), and Nice (2001). However, these modifications have often been criticized, since they failed to introduce forward-looking reforms into the EU’s operations, even in vital matters such as a clear-cut definition of the powers of the EU or the sorely needed reform of its decision-making processes.31

Jacques Santer (1995–1999) was elected Commission president as a result of a compromise. He had hardly any influence on the content of the Treaty of Amsterdam, but he successfully began addressing issues such as the implementation of the monetary union, or the Commission’s personnel reform. Compared with Delors, he had more modest ambitions as a (political) leader—and more modest talent. His presidency ended with the resignation of the entire Commission due to the implication of several commissioners in alleged cases of corruption.32 Jacques Santer was one of those Commission presidents who preferred the role of professional executive to the wielding of political power.

The next Commission president, Romano Prodi (1999–2004), was a full-blooded crisis manager. He played an eminent role in concluding the Treaty of Nice and the preparations for the Constitutional Treaty, but the most significant achievement of this period was the reform of the internal operation of the Commission (the Kinnock reform).33

During Prodi’s Commission presidency, the European Council’s Laeken Declaration established a Convention in December 2001, tasked with formulating and answering the main questions affecting the future of the European Union. This was the period during which the Constitutional Treaty was prepared, but the rejection of the document at French and Dutch referendums brought its ratification process to an end.34 In the eyes of many, this was ample proof that the member states were still unprepared for a constitutional union. In reality, the decision to defend sovereignty against a shift towards federation was made at the last moment. The approach adopted by the Constitutional Treaty still represented a turning point, as its name, its wording, and integration of a catalogue, similar to those of constitutions of a Charter of Fundamental Rights, conveyed the message that a serious step was being taken in the direction of establishing a federation in the future.35

In the eyes of many, this was ample proof that the member states were still unprepared for a constitutional union

The Barroso Commission

José Manuel Barroso, former prime minister of Portugal, headed the European Commission for two cycles (2004–2014). Barroso’s presidency is particularly important in terms of our subject, since the Barroso Commission’s understanding of its political role—especially during its last years—was the direct predecessor of and a model for the Juncker Commission which clearly declared the ideological and political nature of its operation.

Under Barroso, the Commission prepared the REACH directive, the most extensive environmental document in the history of the Commission to date, and also issued the much-debated Bolkestein directive aimed at a major reform of regulations on the free flow of services. After the failure of the Constitutional Treaty, the Barroso Commission’s most important achievement was the ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon (2009) by the member states, which further deepened integration, albeit more carefully than the provisions of the Constitutional Treaty.36

The Commission’s aspiration for an independent political role can be illustrated by Barroso’s action in connection with Hungary. Heads of several European institutions expressed their concern upon seeing, in 2010, the second Orbán government taking power with a two-thirds majority in Parliament. Apart from the active application of infringement procedures, Barroso also crossed a line which can be considered problematic from the perspective of constitutional law: he strongly criticized the constitution of a member state, and the amendment thereof. Regarding the fourth amendment of Hungary’s Constitution, Barroso expounded in a letter to Prime Minister Viktor Orbán that ‘based on a first legal analysis, the Commission has serious concerns over the compatibility of the Fourth Amendment to the Hungarian Fundamental Law with EU legislation and with the principle of the rule of law’. He also indicated, ‘once the on-going legal analysis carried out by the Commission’s services has been finalized, the Commission will have to take the necessary steps in order to start infringement procedures where relevant’.37 This affair has a special significance: it is not at all self-evident, from a constitutional perspective, that EU law has priority over a member state’s constitution. This is, in fact, the subject of serious professional analyses and constitutional court resolutions.38 Despite this, Barroso believed he had the right to cross this legally unstipulated line and attempt to subdue the constitutional power of a member state acting on the basis of popular sovereignty under Union law. Since then, primarily as a result of the political activism of the Juncker Commission, such debates have become permanent, but it is important to note that this way of exercising power by Commission presidents commenced during the last years of the Barroso Commission.

The Juncker Commission: the Birth of the Political Commission

Frédéric Mérand, who published a book earlier this year titled The Political Commissioner: A European Ethnography, characterized the Juncker Commission as follows: ‘A “Political Commission” evokes the Juncker Commission. The Juncker Commission was an experiment related to a larger phenomenon: the politicization of the EU. To understand what a political Commission is, there are many elements to take into account, but the overarching idea was that the Commission should behave like an executive body, responsive to public opinion and accountable to Parliament. In other words, it should behave much like a government.’39

His critics maintain that Juncker’s misdirected political activism caused a great deal of damage to Europe, as the most severe migration crisis and the British decision to leave the Union both occurred during his tenure

In Juncker’s own words, ‘The European Council proposes the President of the Commission. That does not mean he is its secretariat. The Commission is not a technical committee made up of civil servants who implement the instructions of another institution. The Commission is political. And I want it to be more political. Indeed, it will be highly political.’40 Earlier, Juncker had been the prime minister of Luxembourg, and was active in European politics in the 2000s. He was Commission president between 2014 and 2019. His critics maintain that Juncker’s misdirected political activism caused a great deal of damage to Europe, as the most severe migration crisis and the British decision to leave the Union both occurred during his tenure. Nevertheless, his supporters have claimed that by laying the foundations of the ‘political Commission’ he made the executive body of the EU more effective, which also means that the decision-making process of the EU has become more effective.

There were conflicts already around Juncker’s election. The European Parliament (EP) put Section (7) of Article 17 of the Treaty of Lisbon—stipulating that the European Council has to take the result of European elections into account when nominating the Commission president—in an entirely different light. Their idea was that the parties in the EP would nominate candidates, and the European Council would declare the candidate of the winning party the Commission president. The method was proposed by the Commission itself, which was recorded by the European Parliament in a decision.41 This is the so-called Spitzenkandidat system, which triggered strong criticism from the governments of member states. The system was necessary— especially for Juncker—to democratize the Commission, to some extent, since one of the often-voiced concerns regarding the Commission had been that its members made politically sensitive decisions as unaccountable bureaucrats without democratic legitimacy. The Spitzenkandidat system was conceived, presumably, to mitigate this issue.

Numerous ideologically charged examples can be cited from the Juncker Commission’s period in office when it clearly responded to a given situation as a supranational government. ‘The political Commission was for the first time accepted by all member states in July 2018, amid the trade war with the United States that Donald Trump had started’ when ‘suddenly, all member states gave their trust to President Juncker when he conducted the negotiations with Trump’, and conducted them successfully, according to Selmayr.42

In my view, Juncker’s understanding of the Commission’s political role was most evidenced by his (and its) reaction to the migrant crisis in 2015, including the ensuing conflict with Hungary and Viktor Orbán.

Juncker urged a common asylum policy and the furthering of ‘a new European policy on legal migration’ in his programme.43 At the same time, a statement he made in 2016 illuminates his personal (ideological) view on border protection: ‘Borders are the worst invention ever made by politicians.’ Theresa May’s response made it clear that this was not something a prime minister of a member state would say.44 It is important to understand Juncker’s ideological affiliation, since in his political activism he certainly used the Commission and its powers to realize his own vision. This can be demonstrated with the text of the European Agenda on Migration, prepared by the Commission in 2015, which defined a refugee allocation mechanism and schemes for relocation and resettlement.45 On the basis of this agenda, the European Council issued a decision which was challenged by the Hungarian government before the European Court of Justice.46 All of us are aware of the consequences of the migration crisis. Brussels’s solution has been a total failure, and the extraordinary situation has since been handled by each nation state in its own way. It is no exaggeration to say that the actual events in this regard have hardly provided additional leverage for arguments for a federative Europe.

The politically oriented activity of the Juncker Commission was not curbed even after its handling of the migration crisis which had, by all objective criteria, failed. The Commission submitted a white paper to the Rome summit on the future of Europe in March 2017. Juncker’s initiating role was also evident here: ‘The White Paper sets out five scenarios, each offering a glimpse into the potential state of the Union by 2025 depending on the choices Europe will make. The scenarios cover a range of possibilities and are illustrative in nature. They are neither mutually exclusive, nor exhaustive.’47 A review of the scenarios could also be of interest regarding our subject, but I only want to make the point here that Juncker’s political activism had a major impact on European politics.

A third example, on the organizational level, which illustrates Juncker’s creed, is that he explained the restructuring of his relationship with the commissioners by referring to his political mandate. The most spectacular instance of this occurred in 2018, when he appointed a loyal political ally (the head of his private office) secretary-general of the Commission. This development was also significant because it gave the top position in the Commission’s organization, which is. supposed to be politically neutral, to Martin Selmayr.48

These examples are sufficient to confirm the fact that Juncker’s understanding of his political role had real and rather serious consequences. We can conclude, then, that Juncker’s political Commission was one of the most ideologically dominated Commissions. When Frédéric Mérand explains the objective of his new book, he says he is interested in ‘how people in the Juncker Commission systematically tried to push the boundaries of political agency: how they tried to carve out a space in which it would be possible to make political choices between conflicting values’.49 We have every reason to believe that this is a precise description of the focus of the Juncker Commission’s activities.

Summary

When looking at the limits of the Commission’s powers, as stipulated in the Treaties, we can see that although they have clearly been extended in line with the expansion of the scope of policies, on an institutional level the Union is still only halfway between federation and intergovernmental cooperation. The Commission’s powers at this stage cannot match those of a national government, but Commission presidents’ understanding of their political role and a highly creative application of their powers allow them to have a say not only in policy issues but also in the most elemental ideological issues affecting integration (e.g. migration). This loose interpretation of exercising powers has been exemplified in the purest form by the Juncker Commission, which expressly intended to operate as a political Commission, as evidenced by its self-definition. This phenomenon, however, is cause for serious concern. Frequent charges against the Commission are predominantly based on the fact that it lacks democratic legitimacy for making decisions regarding issues of ideology, and it is not held accountable by anyone for its political decisions, which would certainly be unthinkable in democratic circumstances.

Frequent charges against the Commission are predominantly based on the fact that it lacks democratic legitimacy for making decisions regarding issues of ideology

The history of integration has shown that the extension of the Commission president’s powers and his political activism depend on the person holding the post, and that they inevitably go together with the creed of federalism. Most Commission presidents’ top priority has been to deepen integration, thus ‘governmentalizing’ the organization under their supervision. Surveys have effectively confirmed that contrary to any claims and statements of the Commission’s ideological independence, most of its members firmly believe that the Commission’s main task is to be the driving force of the EU. Additionally, a common ‘supranational culture’ seems to prevail in this circle, the central mission of which is the building of a new Europe and the advancement of the European project.50

Commission presidents with the strongest political ambition, however, have repeatedly encountered strong opposition, as sovereigntist heads of state and governments standing on the solid foundation of nation states have also stood up for their own vision of Europe; this analysis offered a reminder of some of the ‘duels’ between them (Hallstein–de Gaulle; Delors–Thatcher; Juncker–Orbán).

In conclusion, the era of heated debates is certainly not over yet. We can see that the two opposing camps have remained unchanged. The same struggle is still ongoing between the representatives of the two visions of Europe, and what the final outcome of this struggle will be is one of the most fundamental questions, one of the crucial issues regarding the future of Europe.

Translated by Balázs Sümegi

NOTES

1 ‘The European Commission as a Political Engine of European Integration, Frédéric Mérand in conversation with Martin Selmayr’, 27 April 2021, geopolitique.eu/en/2021/04/27/the-european- commission-as-a-political-engine-of-european- integration-in-conversation-with-martin-selmayr/.

2 Neill Nugent and Mark Rhinard, ‘The “Political” Roles of the European Commission’ (published online, 8 February 2019), www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.10 80/07036337.2019.1572135.

3 János Bóka, Katalin Gombos, and László Szegedi, Az Európai Unió intézményrendszere (The Institutional System of the European Union) (Budapest: Dialóg Campus Kiadó, 2019), 54.

4 László J. Nagy, Az európai integráció politikai története (The Political History of European Integration) (Szeged: 2005), 25, publicatio.bibl.u- szeged.hu/3325/1/EUINTEGR.pdf.

5 European Commission, www.cvce.eu/obj/ european_commission-en-281a3c0c-839a-48fd-b69c- bc2588c780ec.html.

6 European Commission, www.cvce.eu/obj/ european_commission-en-281a3c0c-839a-48fd-b69c- bc2588c780ec.html.

7 The official website of the European Commission, europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/institutions- bodies/european-commission_hu.

8 Nagy, Az európai integráció politikai története, 32. 9 Treaty on European Union (TEU), Section (2) of Article 17.

10 TEU, Section (3) of Article 17.

11 TEU, Section (5) of Article 17.

12 Nugent and Rhinard, ‘The “Political” Roles of the European Commission’.

13 The European Commission as a Political Engine.

14 Nugent and Rhinard, ‘The “Political” Roles of the European Commission’.

15 Nugent and Rhinard, ‘The “Political” Roles of the European Commission’.

16 Walter Hallstein, ‘Egy diplomata a gyors európai integráció szolgálatában’ (A Diplomat in the Service

of Rapid European Integration), n.d., europa.eu/ european-union/sites/default/files/docs/body/walter_ hallstein_hu.pdf.

17 Krisztina Arató and Boglárka Koller, Az európai egység fejlődéstörténete és az EU jelenkori kihívásai (History of the Development of European Unity and Current Challenges of the EU) (Budapest: Dialóg Campus Kiadó, 2018), 13.

18 Nagy, Az európai integráció politikai története, 41.

19 ‘Historical Events in the European Integration Process (1945–2014). The Empty Chair Crisis’, www.cvce.eu/en/ recherche/unit-content/-/unit/02bb76df-d066-4c08-a58a- d4686a3e68ff/62cd6534-f1a9-442a-b6f b-0bab7c842180.

20 ‘De Gaulle and Europe’, web.archive.org/ web/20061118185240/http://www.charles-de-gaulle. org/article.php3?id_article=178.

21 The official website of the European Council, www. consilium.europa.eu/hu/european-council/.

22 The official website of the European Parliament, www.europarl.europa.eu/about-parliament/en/in-the- past.

23 Tamás Fricz, Európa és Unió (Europe and Union) (2 December 2019), 26, alapjogokert.hu/wp-content/ uploads/2019/12/europa_unio_teljes.pdf.

24 Arató and Koller, Az európai egység fejlődéstörténete, 17.

25 Nagy, Az európai integráció politikai története, 47.

26 www.newstatesman.com/politics/uk/2021/01/ rupture-between-margaret-thatcher-and-jacques- delors-lives-brexit.

27 Charles Grant, Delors. Inside the House that Jacques Built (London: Nicholas Brearley, 1994), 135.

28 ‘Speech in Lorient’ (29 August 1993), quoted by The Times (30 August 1993), 11.

29 Arató and Koller, Az európai egység fejlődéstörténete, 20.

30 Arató and Koller, Az európai egység fejlődéstörténete, 19.

31 matarka.hu/koz/ISSN_0866-6032/ tomus_25_1_2007/ISSN_0866-6032_ tomus_25_1_2007_175-190.pdf, 177.

32 Bóka, Gombos, and Szegedi, Az Európai Unió, 55.

33 Bóka, Gombos, and Szegedi, Az Európai Unió, 55.

34 matarka.hu/koz/ISSN_0866-6032/ tomus_25_1_2007/ISSN_0866-6032_ tomus_25_1_2007_175-190.pdf , 118.

35 Arató and Koller, Az európai egység fejlődéstörténete, 24.

36 ‘The constitutional treaty was an easily understandable treaty. This is a simplified treaty which is very complicated.’ On the Lisbon Treaty, 23 June 2007, www.nzz.ch/2007/06/24/eng/ article7955045.html.

37 ‘The European Commission Reiterates Its Serious Concerns over the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution of Hungary’, European Commission, ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/hu/ ip_13_327.

38 See: ‘The Constitutional Court of Poland Declares the Decision of the European Court of Justice Unconstitutional’, index.hu/kulfold/2021/07/14/ lengyel-alkotmanybirosag-alkotmanyellenes- eu-birosag-dontes/.

39 ‘The European Commission as a Political Engine of European Integration.’

40 ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ SPEECH_14_567.

41 Arató and Koller, Az európai egység fejlődéstörténete, 26.

42 ‘The European Commission as a Political Engine of European Integration.’

43 A New Start for Europe: My Agenda for Jobs, Growth, Fairness and Democratic Change. Jean-Claude Juncker’s presidential programme (Strasbourg, 15 July 2014), web.archive.org/web/20160923014309/http://ec.europa.eu/priorities/sites/beta-political/files/ pg_hu.pdf.

44 Juncker, ‘Borders Are Worst of Inventions’, www. thetimes.co.uk/article/juncker-borders-are-worst- of-inventions-5rgw9kb33.

45 ‘The Commission’s Communication to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, and the Committee of the Regions. The European Agenda on Migration’ (Brussels, 13 May 2015), ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/default/ files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/ background-information/docs/communication_on_ the_european_agenda_on_migration_hu.pdf.

46 See ‘EU’s Top Court Dismisses Hungary and Slovakia Case against Refugee Quotas’, hu.euronews. com/2017/09/06/kvotaper-elutasitotta-a-magyar-es- szlovak-keresetet-az-europai-birosag.

47 https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/ hu/IP_17_385.

48 Nugent and Rhinard, ‘The “Political” Roles of the European Commission’.

49 ‘The European Commission as a Political Engine of European Integration.’

50 Nugent and Rhinard, ‘The “Political” Roles of the European Commission’.