Farmers are organizing demonstrations in more and more European countries. The protests have been going on for more than a month in Germany and two weeks in Romania, and now the wave of protests has also reached France, Poland, and Greece, and could spread even further in the coming weeks, reaching Spain and Italy, too. Farmers mainly complain about increasingly strict regulations, and growing costs coupled with ever decreasing subsidies. How does the wave of discontent spreading across Europe affect the upcoming European Parliament elections?

Tractor demonstrations are becoming ever more widespread in Europe: after Germany, Romania, and France, which is the biggest agricultural producer in the EU,

a national demonstration was also held in Poland this week, as farmers demand protection against Ukrainian imports.

According to the farmers, while they have to comply with very strict regulations and costly environmental protection rules, the same does not apply to the manufacturers of imported products. Therefore, EU agricultural producers suffer from a competitive disadvantage.

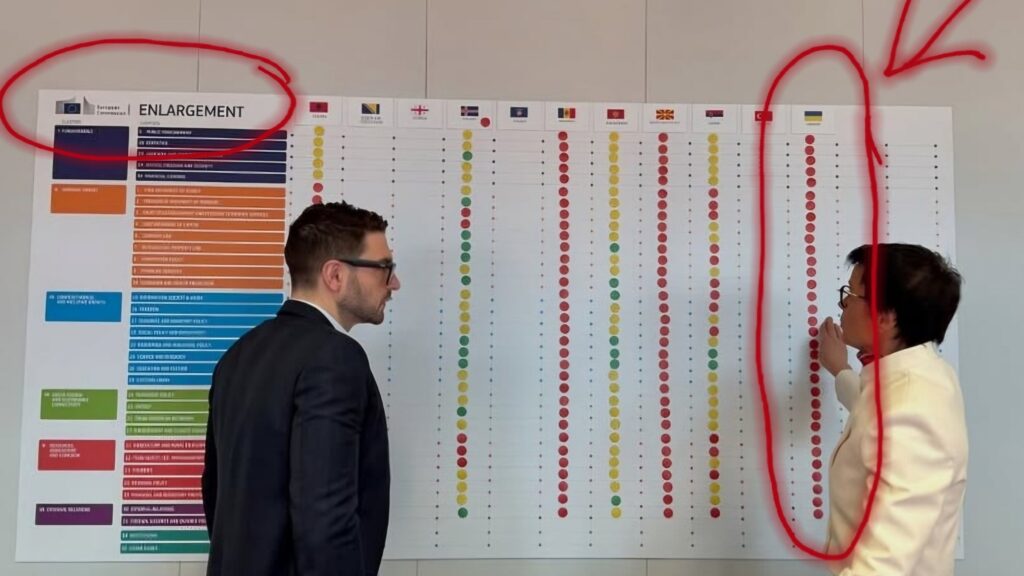

The demonstrators are also demanding that the Warsaw government prepare a detailed plan for Ukraine’s possible EU accession, broken down by sectors. But the farmers have problems not only with their war-torn eastern neighbour but also with the EU’s agricultural policy. They want to get Brussels to review the common European agricultural policy (CAP). In addition, they are also dissatisfied with the green transition strategy that is being implemented in Europe, seen as imposing too many restrictions on farmers. Polish farmers would like to see greater flexibility from decision-makers.

The situation is similar in Greece. As reported by local news sources, issues related to the implementation of the new CAP are at the centre of the farmers’ concerns. In Romania and Bulgaria, border crossings have been jammed by tractors and trucks.

The wave of protests started last year in Germany, where farmers took to the streets against the government’s planned subsidy cuts, saying that the move would jeopardize their livelihoods. The protesters blocked several motorways and city centres over the past three weeks.

Dissatisfaction is also growing in France, where roads have been blocked across France, with manure and agricultural waste being dropped outside public offices, and bales of hay spread through fast food restaurants. Emotions were further fuelled by a tragedy this week, when a farmer and her daughter were killed, and her husband seriously injured in a traffic collision at a protest barricade in the Ariège region in southwestern France.

According to analysts, protests could spread even further in the coming weeks with Spanish and Italian farmers poised to join the movement. On Thursday, the European Commission started strategic talks with farmers’ unions, agriculture businesses and experts seeking to put out the fire. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said: ‘The time is ripe to forge a new consensus on food and farming among farmers, rural communities and all other actors on the EU agri-food chain.’

But, as tensions continue to grow, agriculture is set to become a major issue across the EU ahead of the European Parliament elections in June.

The general dissatisfaction is also reflected in opinion polls: the latest survey of the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) indicates that the political right is expected to strengthen in the June elections. As the survey report put it, ‘anti-European populists’ are lead the polls in nine member states: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Slovakia; and they come second or third in a further nine countries that include Bulgaria, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Portugal, Romania, Spain, and Sweden.

According to the survey, a right-wing coalition of Christian democrats, conservatives, and radical right MEPs could emerge with a majority for the first time in the European Parliament.

Brussels-based POLITICO’s survey also foretells a right-wing turn just five months before the elections, reflecting a public mood which is clearly of concern for the Brussels elites. The forecast of the left-leaning news portal suggests that the Identity and Democracy group, which currently has 58 members, could win almost 90 seats in June’s European election, adding around 15 extra MEPs to the European Parliament, taking the total number to 720.