This article was published in our print edition’s Special Issue on the European Union.

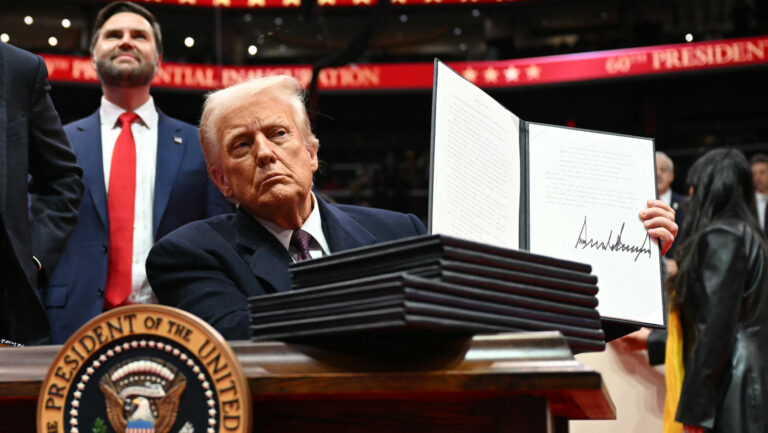

There is a widespread view that Germany is the EU’s hegemon. Or, to quote Donald Trump, that the EU is a ‘vehicle for Germany’.1 If it is not yet a hegemon, it should certainly become one, albeit a friendly one, Thomas Schmid argued in Die Welt, back in 2012.2

Perceived German influence in EU structures may well have been one reason for Brexit—Brits do not like the thought of being dominated by the country they fought two world wars against. There is a similar backlash in France, palpable in the rise of Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National Party and her stinging characterization of François Hollande, France’s president at the time, as Angela Merkel’s ‘vice-chancellor, administrator of the province of France’.3 When Greece almost went bankrupt in the financial crisis that shook the world in 2008–2009, and Germany became a decisive factor in imposing a policy of austerity on the Greek government, Greek media depicted Chancellor Angela Merkel with a swastika.4 German historian Andreas Rödder wrote a book about this fear of German domination: Wer hat Angst vor Deutschland? (Who Is Afraid of Germany?). His answer: ‘Everybody, including the Germans themselves. They are afraid of leading.’5

Ironically, the whole purpose of creating a transnational European structure was to prevent Germany from becoming a hegemonic power ever again. It was a French idea. The aim was to bind Germany in a way that would make it impossible for it to dominate anyone or anything anytime soon.

Until recently, if you asked German politicians, that is exactly how they saw themselves. Domination? Where? How? ‘We don’t understand why people feel that way’, one foreign policy official once told me. ‘We don’t feel that we dominate, or that we would want to do so.’ For them, German dominance was a perception, not a reality. Indeed, while Hungary—to pick a random example—is always keen to announce its stance on contentious issues, and to use its vote in EU institutions to defend its national interests, Germany has rarely been outspoken about what it wants. A ‘German vote’, in EU parlance, means an abstention. It may be that Germany does not want to be seen as forcing a cause, or else (more often than not) that coalition partners in Berlin cannot agree on a common position.

‘The left-wing, three-party coalition currently in power is the weakest and most unpopular government modern Germany has ever had’

‘German policymaking is typically reactive’, says Volker Beck, of German think-tank Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP). According to that analysis, Germany waits for things to happen, and when they do happen, it will try to not act until doing so becomes unavoidable. This was encapsulated by Poland’s then Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski in 2011, when he famously said that he feared Germany’s power less than Germany’s inactivity.6 That may explain why it was so late to react in the Migration Crisis of 2015–16. By the time Angela Merkel opened Germany’s borders to illegal migrants (and thus took a decision), Hungary had already completed its much-maligned border fence. Remarkably, Robin Alexander’s reconstruction of events in his book Die Getriebenen7 comes to the conclusion that initially, Merkel wanted to close rather than open the border, but decided against it out of fear of a negative media reaction. Reactive policymaking indeed. Germany’s slow and opaque stance on helping Ukraine in its war against the Russian invasion can also be seen as reactive rather than proactive.

But does reactive policymaking make any sense? One should think that waiting until the last moment would limit options in any situation. Even when Germany does want to force an issue, it usually does not want to be perceived as doing so. Refugee quotas? The EU commission’s idea. Rule of law conditionality? The Dutch wanted to protect taxpayers’ money.

One reason for Germany’s caution is of course a certain degree of self-consciousness—the country that produced Nazism wants to be seen as kind and respectful, not powerful or dominant. Yet all others know that it is indeed powerful, and interpret even Germany’s silence. ‘Even when we do nothing, others read meaning into that’ is a phrase I have often heard from various German experts and officials over the years. Whatever Germany does or, more often, does not do, there is a lingering question in the back of other countries’ minds: What do the Germans really want? What is their strategy? But of course, if German policy really is reactive, it is hard to see how it can develop forward-looking strategies at all.

However, recently things have been changing. The left-wing, three-party coalition currently in power is the weakest and most unpopular government modern Germany has ever had, but it is also one that is much more eager to formulate long-term strategies than its predecessors. In June 2023, it gave itself a ‘National Security Strategy’.8 Germany had never had one before. A slew of other strategies were also announced: A ‘Digital Strategy’ (2022) and, building on that, an ‘International Digital Strategy’ (2024),9 as well as a ‘Strategy on Climate Foreign Policy’ (2023).10 As for Germany’s EU strategy, it was written into the coalition contract of its governing parties and is probably the most radical official vision of any EU government so far: a strategy to transform the EU into a ‘European federal state’.11

All of these documents state that Germany wants to ‘lead by example’, as a ‘servant leader’—a concept articulated, amongst others, by Leon Mangasarian and Jan Techau in their book Führungsmacht Deutschland (‘Leading Power Germany’).12 That Germany should be, and indeed is, a Führungsmacht has since been openly claimed and/or demanded by a number of German politicians, from Lars Klingbeil, head of the ruling Social Democratic Party (SPD)13 to Defence Minister Boris Pistorius.14

However, for many hardnosed Central European politicians, there can be no such thing as a ‘servant leader’ in politics. There can be no ‘benevolent hegemon’. In politics, countries do not serve the interests of other countries. They serve their own interests, and that is that. Interests can align, of course, and compromises can be found, leading to win-win situations. It has so far been the business model of the EU. But everyone still serves their own best interests. Thus, when German politicians say they want to turn the EU into a federal state, and to lead the way as a ‘servant leader’, conservative Central European politicians tend to believe that they are either lying or delusional. And that if they want a federal European state, it must be because Germany believes that to be in its own interest. It must mean that Germany believes it can dominate such an EU. That it wants to build an empire yet again.

When France’s president Emanuel Macron demands ‘strategic autonomy’ (a decoupling from the United States) for an EU that he wants to become ‘a third superpower’,15 and German politicians nod in agreement, adding that as a Führungsmacht they would like to turn the EU into a federal state, some Central European politicians sense that Germany itself would not mind being a superpower of sorts: the, or at least a, leading power within that superpower.

Germans, in turn, will not understand that perception. They will point to the fact that in the EU, no one state can impose its will. It always takes coalitions. The French–German partnership or, more recently, the revived ‘Weimar Triangle’ consisting of France, Germany, and Poland.

This whole ‘superpower’ philosophy is radically transforming the EUs character. It used to be a clearinghouse of economic cooperation in areas of shared interest. Now, the narrative is about needing to ‘speak with one voice’ in order to have an impact in geopolitics. In other words, a desire to be able to act like a nation state. That can only happen to the detriment of the sovereignty of existing nation states within the EU.

Recently, at a brainstorming workshop with German and Hungarian think-tankers, policy advisers, and government representatives was held under Chatham House rules, and the German side described what they saw as future challenges and necessities in the EU. Enlargement would necessitate streamlined decision-making, an end to the veto rule, and an end to the principle that every country should get to have a commissioner in the EU commission. The aim should be to make the EU more ‘capable of action’. Also, the Germans thought it necessary to ‘refocus on the EU’s single market’ in a world economy now impacted by ‘deglobalization, repoliticization, and decarbonization’. That renewed focus on the single market would demand a tightening of rule-of-law conditionalities, and their extension to any and all EU policy domains.

‘Germany’s EU strategy…is probably the most radical official vision of any EU government so far: a strategy to transform the EU into a “European federal state”’

Hungarian participants pointed out that deglobalization was a bad thing, the repoliticization of economic cooperation was also bad, and that decarbonization was not necessarily good for the EU’s global competitivity. And was it not a fact that the EU’s share of the global economy was shrinking, and would further shrink? Why then ‘refocus’ on the EU’s single market, rather than seeking increased global cooperation? All true, said the Germans, but ‘there is no other choice’. It sounded reactive (these things are happening anyway, we cannot help it) as opposed to the Hungarian urge to be proactive (let us try a different way). What the Germans were describing was an EU in which nation states would barely have any autonomy anymore, in order to create an EU capable of acting like a state in its own right.

The problem is that within such a structure, situations would inevitably arise in which conflicting national interests would not be solved by compromise, but by brute power—one group of countries would be able to impose its will on other member states. It would be the end of an EU in which win-win outcomes are the norm. It would generate win-lose situations, or in other words, conflict. For a strategy seeking to strengthen the EU, that might be a weakness.

NOTES

1 ‘Donald Trump Takes Swipe at EU as ‘Vehicle for Germany’, Financial Times (16 January 2017), accessed 3 April 2024.

2 Thomas Schmid, ‘Eine neue Vision für Europa’ (A New Vision of Europe), Die Welt (28 June 2012), accessed 3 April 2024.

3 ‘Vice-chancelier”: Hollande moqué par Le Pen’, Le Figaro (7 October 2015), accessed 3 April 2024.

4 ‘Furious Greeks Lampoon German “Overlords” as Nazis’, Daily Mail (28 October 2011), accessed 3 March 2024.

5 Andreas Rödder, Wer hat Angst vor Deutschland? Geschichte eines Europäischen Problems (Who Is Afraid of Germany? History of a European Problem) (S. Fischer Verlag, 2018).

6 Radosław Sikorski, ‘Deutsche Macht fürchte ich heute weniger als deutsche Untätigkeit’, speech given on 28 November 2011, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Auswärtige Politik, https://dgap.org/de/veranstaltungen/deutsche-macht-fuerchte-ich-heute-weniger-als-deutsche-untaetigkeit, accessed 4 April 2024.

7 Robin Alexander, Die Getriebenen. Merkel und die Flüchtlingspolitik: Report aus dem Inneren der Macht (The Compelled. Merkel and Refugee Policy: An Insider Account) (Siedler Verlag, 2018).

8 ‘Nationale Sicherheitsstrategie’ (National Security Strategy), www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/aktuelles/nationale-sicherheitsstrategie-2195890, accessed 4 April 2024.

9 ‘Strategie für die Internationale Digitalpolitik der Bundesregierung’ (Strategy for Federal Germany’s International Digital Policy), https://bmdv.bund.de/SharedDocs/DE/Artikel/K/strategie-internationale-digitalpolitik.html, accessed 4 April 2024.

10 ‘Strategy on Climate Foreign Policy of the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany’, www.auswaertiges-amt.de/blob/2633116/a3a08056cef2c3a5aaede4f1afada2c4/kap-strategie-en-data.pdf, accessed 4 April 2024.

11 ‘Mehr Fortschrittt wagen’ (Dare to Go Further), coalition contract published online on, SPD.de (24 November 2021), www.spd.de/fileadmin/Dokumente/Koalitionsvertrag/Koalitionsvertrag_2021-2025.pdf, accessed 4 April 2024.

12 Leon Mangasarian and Jan Techau, Führungsmacht Deutschland. Strategie ohne Angst und Anmaßung (Leading Power Germany: Strategy without Fear and Presumption) (DTV, 2017).

13 ‘SPD-Chef Klingbeil sieht Deutschland als “Führungsmacht”’ (SPD leader Klingbeil Sees Germany as a ‘Leading Power’), Die Zeit (6 June 2022), www.zeit.de/news/2022-06/21/spd-chef-klingbeil-sieht-deutschland-als-fuehrungsmacht, accessed 4 April 2024.

14 ‘Pistorius erklärt Deutschland zur Nato-Führungsmacht’ (Pistorius Declares Germany a Leading NATO Power), ntv.de (27 September 2023), www.n-tv.de/politik/Pistorius-erklaert-Deutschland-zur-NATO-Fuehrungsmacht-article24425865.html, accessed 4 April 2024.

15 ‘Europe Must Resist Pressure to Become ‘America’s Followers”, Says Macron’, Politico (9 April 2023), www.politico.eu/article/emmanuel-macron-china-america-pressure-interview/, accessed 4 April 2024.

Related articles: