Henry Kissinger, in his book Does America Need a Foreign Policy?: Toward a Diplomacy for the 21st Century—published in 2001 years after the US had de facto assumed the role superpower after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and, months before the attacks of 11 September—, forewarned:

‘America’s success in such a world will be measured by a gradual amelioration of a wide variety of political, economic, strategic, and social problems….The American role will prove central to the resolution of many of these, but the United States will drain its psychological and material resources if it does not learn to distinguish between what is must do what it would like to do, and what is beyond its capacities.’[1]

America, in its hegemonic role, very quickly showed itself to be a country of double standards. Its ‘war on terror’ (officially Global War on Terrorism), for example, which was propelled by President George W Bush after the 11 September attacks, opened up a Pandora’s Box as it emboldened autocrats, misallocated resources, fuelled a global migration crisis, and led to an arc of instability from South Asia through North Africa. The pinnacle of this hubris was the invasion of Iraq in 2003, when the US nonsensically attempted what was never tenable — recasting not just Afghanistan (invaded two years before) and Iraq in its own image, but the entire Middle East.

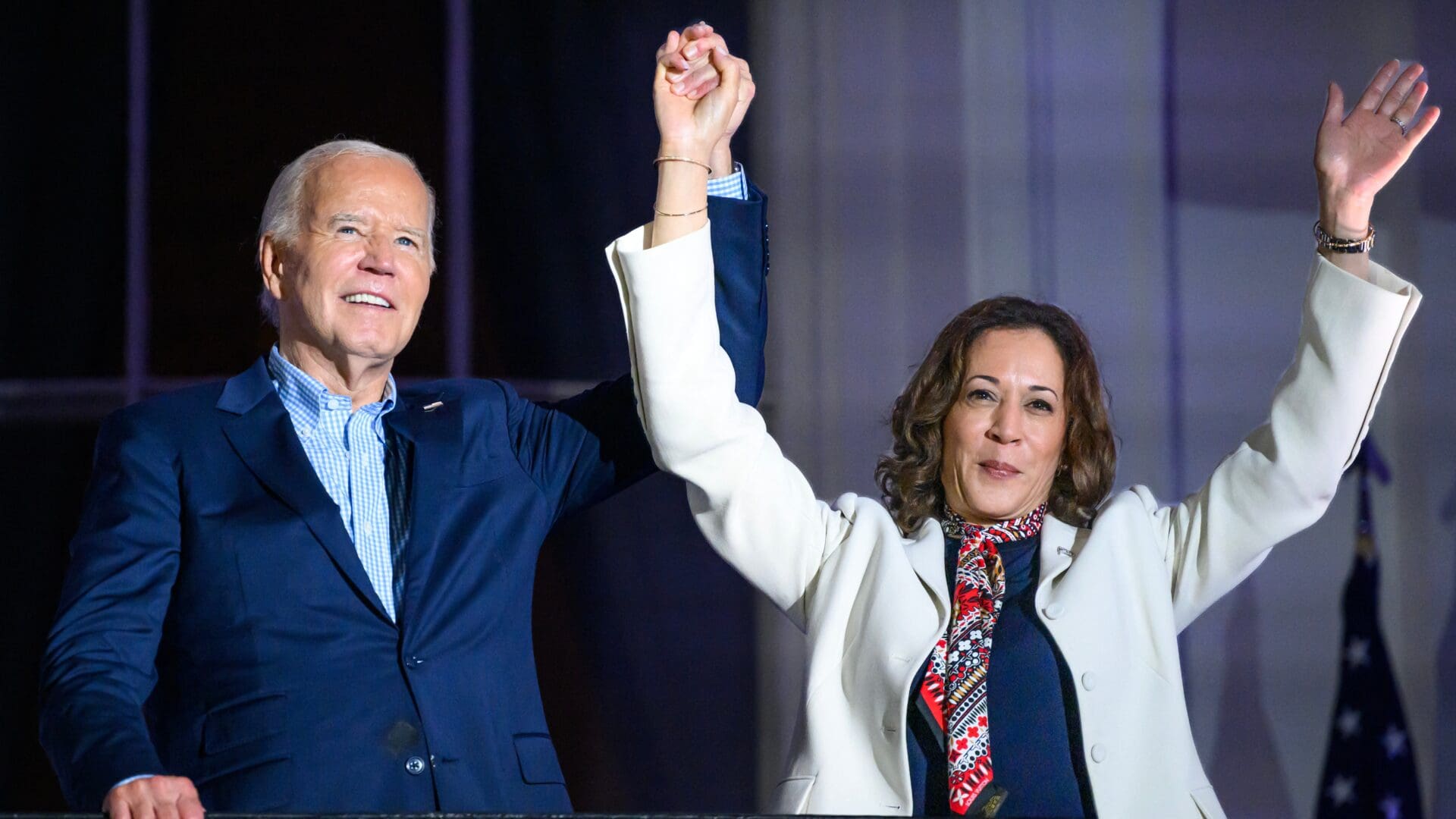

Then came Donald Trump unto the political scene. His ‘America First’ furnished a foreign policy that was viewed in transactional terms, questioned the value of US alliances, and a professed admiration for adversaries. To this, President Joe Biden reacted with his ‘America is back’, a rehash, to a certain point, of US post-Cold War agenda based on diplomacy—both agendas have had their successes and their shortcomings.

Trump’s ‘America First’ — A Rupture from the Post-Cold War Agenda

Donald Trump proved that he was unlike any president before him, at least in the post-World War II era. His ‘America First’ rewrote US foreign policy that excluded the disseminating of American classical liberal values and military or humanitarian interventions in the world, so much so that America was no longer going to sacrifice its own interests for those of others. Indeed, President Trump became bête noire of the political establishment and Republican neoconservatives.

His provocative and unconventional style of politics was also, at times, paradoxically effective. Trump, unlike his four predecessors, can claim that under his administration the US did not engage in any new foreign wars—this is perhaps the greatest result of his foreign policy. While President Biden can claim the same, he has nevertheless entangled America in the wars in Ukraine and Gaza that happened under his watch.

President Trump also negotiated a new trade agreement with South Korea, and updated the the North American Free Trade Agreement, although neither deal marked a dramatic improvement over the prior arrangements. In addition, he brokered the Abraham Accords, which formalized diplomatic relations between Israel, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates, and later Sudan and Morocco, which were seen as part of a larger goal to grow a regional coalition against Iran—which, unfortunately, as we see, did very little to restore peace in the Middle East.

At the same time, Trump’s skepticism of treaties led him to pull out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership on his first day in office. In 2018 he withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (Iran nuclear deal). The aftermath, in part, reflected his moves when he was a private entrepreneur that caused his casinos to become bankrupt, his defunct Trump Shuttle, the $25 million fraudulent settlement to the attendees of his Trump University, and other failed business ventures.

After pulling out of the Iranian nuclear deal, for example, which he called to be among the worst agreements in history, Washington pursued a policy to apply maximum pressure to force the theocratic regime’s capitulation. Subsequently, the president demanded that the international community extend restrictions against Iran for breaking the terms of a nuclear deal he himself had withdrawn from. All but one of the other members of the United Nations Security Council voted against the move or abstained, including every other permanent member of the body. In the end, the regime survived economic pain and popular unrest, even with the additional turmoil of the coronavirus pandemic.

Effectively, Trump’s ‘America First’ had become America alone.

Trump repeatedly threatened to take the US out of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) if member states did not meet the required 2 per cent of their GDP on defence, a huge point of contemplation on the minds of Western and Eastern European leaders. The immediate reading on this is a lack of aptitude and predilection of allies that do have significant monetary value, such as Japan, South Korea or the Arabian Gulf, who host American military base. Or, for that matter, the savings resulting from pre-stocking equipment in allied nations, like in Israel, Kuwait, Japan, Qatar, the Netherlands, and Norway.

Despite all this, Trump is hailed as a pragmatic man, a realist who gets things done. His policies, therefore, became a beacon to which most conservative lawmakers had to orient themselves in both foreign and domestic affairs—or at least they had no choice but to comply if they wanted to hold onto their positions.

Biden’s ‘America is Back’ — A Return to the Post-Cold War Agenda

In his first three and a half years in office, Biden returned to the old rules-based international order. The goal of his ‘America is Back’ was to revitalize the free world’s faith in America through the restoration of diplomacy in order to counter ‘advancing authoritarianism [by] championing opportunity, upholding universal rights, respecting the rule of law, that can only be solved by nations working together’.

The Biden administration has been partially successful in this, as with unifying the member states of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in order to better confront the Russian aggression towards Ukraine. Also, concerning the Indo–Pacific economic alliance in 2022 that brought together India, Japan and South Korea, Australia, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam—all of which represent about 40 per cent of the world economy. It was, in fact,

a full reversal of Trump’s isolationist doctrine,

which impugned the security alliance between the US and Japan, notwithstanding China’s aggression, unsuccessfully pressed South Korea to pay five-fold more to house US troops, and approved of then-Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s plan to terminate a visiting forces agreement with the US military.

Yet Biden’s ‘America is Back’ became stagnant for the simple reason that the so-called values of the past he cherishes are no longer in place. Even though the laws, structures, and summits remain, the core institutions, like the UN Security Council and the World Trade Organization, Ben Rhodes, author of After the Fall: Being American in the World We’ve Made, says, ‘are tied in knots by disagreements among their members’. Both the Russian Federation and Communist China, for example, whilst being part of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, have remained fully committed to establish an alternative order that would disrupt US-fortified norms. Not that they have truly succeeded in this, but regional powers such as Brazil, India, Turkey, and the Gulf states can now pick and choose which partner to plug into, depending on the issue. And thus far, the US has not been their go-to-choice.

Even though Biden did not adapt President Obama’s embarrassing ‘lead from behind’ strategy, his disconcerted, if not chaotic, withdrawal from Afghanistan

communicated both weakness and that America has turned its back on the world.

Last, but not least, his unrealistic attempt to rejoin the Iran nuclear deal: his failure only incremented its uranium production to get even closer to building a nuclear warhead and further made its mark in the Middle East.

Biden’s abrupt exit from the presidential race and anointment of Vice President Kamala Harris as his would-be successor has certainly left world leaders in disarray—not that they were not expecting it, given the obvious lack of both physical stamina and mental acuity of the US president. Regardless, as they continue to grapple with the wars in Ukraine and Gaza, an escalation in the Middle East, and a more emphatic China, world leaders are contemplating if there will be a second Trump’s ‘America First’ administration or a continuity of Biden’s ‘America is Back’ through Kamala Harris.

[1] Henry Kissinger, Does America Need a Foreign Policy?: Toward a Diplomacy for the 21st Century, New York, Simon & Schuster, 2001, 283–4.

Read more from the author: