Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán has always been active in seeking sovereigntist allies in his battle against the EU’s federalist ambitions. With the victory of Giorgia Meloni, Hungary seems to have gained a new ally in the fight.

Italy Turning Right

On 25 September, Italy held early general elections after the collapse of the government led by centrist technocrat Mario Draghi. With 26 per cent of the vote, the right-wing conservative party of Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy will lead the centre-right-wing unity government and Meloni herself will become Italy’s first female prime minister.

Meloni’s victory is also significant considering that her party only received 4 per cent of the vote in the last election. While remaining in opposition, Meloni has gradually won voters’ trust by emphasising national sovereignty over the EU, opposing illegal immigration, and as a ’pro-family’ woman expressing her conservative views through calling for the protection of children against LGBTQ propaganda, opposing abortion, euthanasia, and same-sex marriage.

Besides Brothers of Italy (FdI), the set-to-govern coalition also includes the former minister of interior Matteo Salvini’s League (Lega) and Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia—both parties received around 8 per cent of the votes. The main message of Salvini’s party is the rejection of illegal immigration, which has been a serious problem for Italy for years. 86-year-old Silvio Berlusconi is a prominent figure in Italian and European politics, having been prime minister of the country for almost a decade and his party, Forza Italia, is considered the most centrist and most pro-EU of the three right-wing formations.

The rise of right-wing—and in particular, non-establishment parties—has of course been fuelled by the Italian government’s misguided crisis management strategy, including both the 2015 refugee crisis and the fight against the Covid pandemic. The latter affected Italy extremely badly, which, as it turned out, was also due to the mishandling of the crisis by the Draghi government.

Von der Leyen: We Have Tools…

With the election of Meloni, Brussels’ nightmares of a renewal of European conservative power seem to be taking shape. Days before the Italian elections, when the victory of the right appeared increasingly certain, Brussels seemed to be setting the rules of the game in advance with Italy turning to the right.

On 23 June, Ursula van der Leyen infamously threatened Italy in the q&A session that followed her lecture at Princeton University. (For more Hungarian Conservative commentary on the remarks, read our sarticle of 24 September.) The ‘tools’ that von der Leyen referred to with which the Commission can discipline unruly Member States include various procedures, that currently both Hungary and Poland are undergoing. Poland is under Article 7 proceedings for curtailing the independence of the judiciary, which in extreme cases can lead to the suspension of voting rights. Hungary is also under such proceedings, but Budapest is also being targeted by the European Commission under the so-called rule of law mechanism, which last week recommended to the European Council that €7.5 billion of funding be suspended.

Von der Leyen’s comment triggered deep outrage not just in Italy but among conservative figures internationally. As opposed to that, after Meloni’s victory, Socialist Vice-President of the European Parliament Katarina Barley didn’t hesitate to symbolically join von der Leyen and voice ominous disapproval stating ‘Europe is facing difficult times because Giorgia Meloni will be a prime minister whose political idols are Viktor Orban and Donald Trump. Meloni would give the autocrats ‘a lobbyist in the Council’ to ‘throw sand in the EU machine’, she warned stating that Meloni is a ‘threat to constructive European cohesion’.

But what could Meloni’s victory really mean for the European conservative camp—called autocrats by Ms Barley—and especially for its central figure, Viktor Orbán?

Changing the Power Balance in the EU

Although in the run-up to the elections, Giorgia Meloni deliberately backed away from his anti-Brussels rhetoric, experts believe the new Italian government will act as a natural ally of Hungarian and Polish Eurosceptics in EU debates. And a victory for the Italian centre-right alliance could significantly change the balance of power in Europe.

As for the conservative bloc of parties in the European Parliament, it is hard to ignore the fact that the already strong Reformists and Conservatives Group—which includes both the Polish and Czech prime ministers—could now potentially be joined by another prime minister allied with Budapest: Giorgia Meloni.

Similarly, the situation of the League led by Matteo Salvini, which could play a significant role in the Identity and Democracy Group, could be assessed in the light of the fact that Salvini is certain to have a key position in the new Italian government that will be formed in the coming weeks.

And perhaps the most important issue for Budapest and Warsaw is the composition of the European Council, as it is the EU body that ultimately decides on the funds that Hungary, Poland and Italy are in fact entitled to. From that perspective, with the recent conservative victory in Italy, Budapest and Warsaw have gained a serious ally in defending their interests.

Conservative Renaissance

Viktor Orbán has always been active in seeking sovereigntist allies in his battle against the EU’s federalist ambitions. Finding friendly forces became even more compelling for Orbán after his Fidesz party left the European Parlament’s European People’s Party (EPP) in March 2021. At that time, Warsaw seemed to be Budapest’s only staunch ally.

After Fidesz left the EPP, consultations between Lega President Matteo Salvini, Viktor Orbán and Polish PM Mateusz Morawiecki started. The emerging movement is being described as a ‘European conservative renaissance’ by the cooperating parties, aiming to end the essentially left-wing dominance in the European Parliament that seeks to exert political pressure on Brussels decision-making bodies, especially the European Commission. Now the victory of the Italian right could give a new impetus to this movement that began in Budapest last year.

The allied conservative forces aim to make the EU return to the original concept of a united Europe envisioned by the founding fathers, one based on the voluntary alliance of nations. The movement offers an alternative to the left, and is based on shared values such as work, health, identity, Christian values, family, security and national sovereignty.

‘He is one of the souls, one of the driving forces of the movement. It is no coincidence that our first meeting was held in Budapest. I believe that Hungary, Poland and Italy are friendly nations and related political forces. Orbán had the strength to leave the increasingly left-wing European People’s Party. And the League and the Poles are at his disposal to do something new,’ Salvini said after the summit.

In July 2021, right-wing parties from 16 EU countries, including France’s Rassemblement National, Poland’s PiS, Hungary’s Fidesz, and Italy’s League, signed a document declaring the need of right-wing parties joining forces to reform the EU. ‘The cooperation of European nations should be based on tradition, respect for the culture and history of European states, respect for Europe’s Judeo-Christian heritage and the common values that unite our nations, and not on their destruction,’ the signatories pointed out. In late January 2022, right-wing national conservative European leaders also agreed on a roadmap for a patriotic Europe during a meeting organised by the Spanish Vox party in Madrid.

In April 2022, Hungary’s prime minister visited Italy to meet Matteo Salvini and discuss further steps of forming a European conservative alliance. The former interior minister emphasised that there were areas of full agreement between him and PM Orbán and highlighted the need to work ‘on a European centre-right alternative to the socialists, to defend the values and roots of the West’.

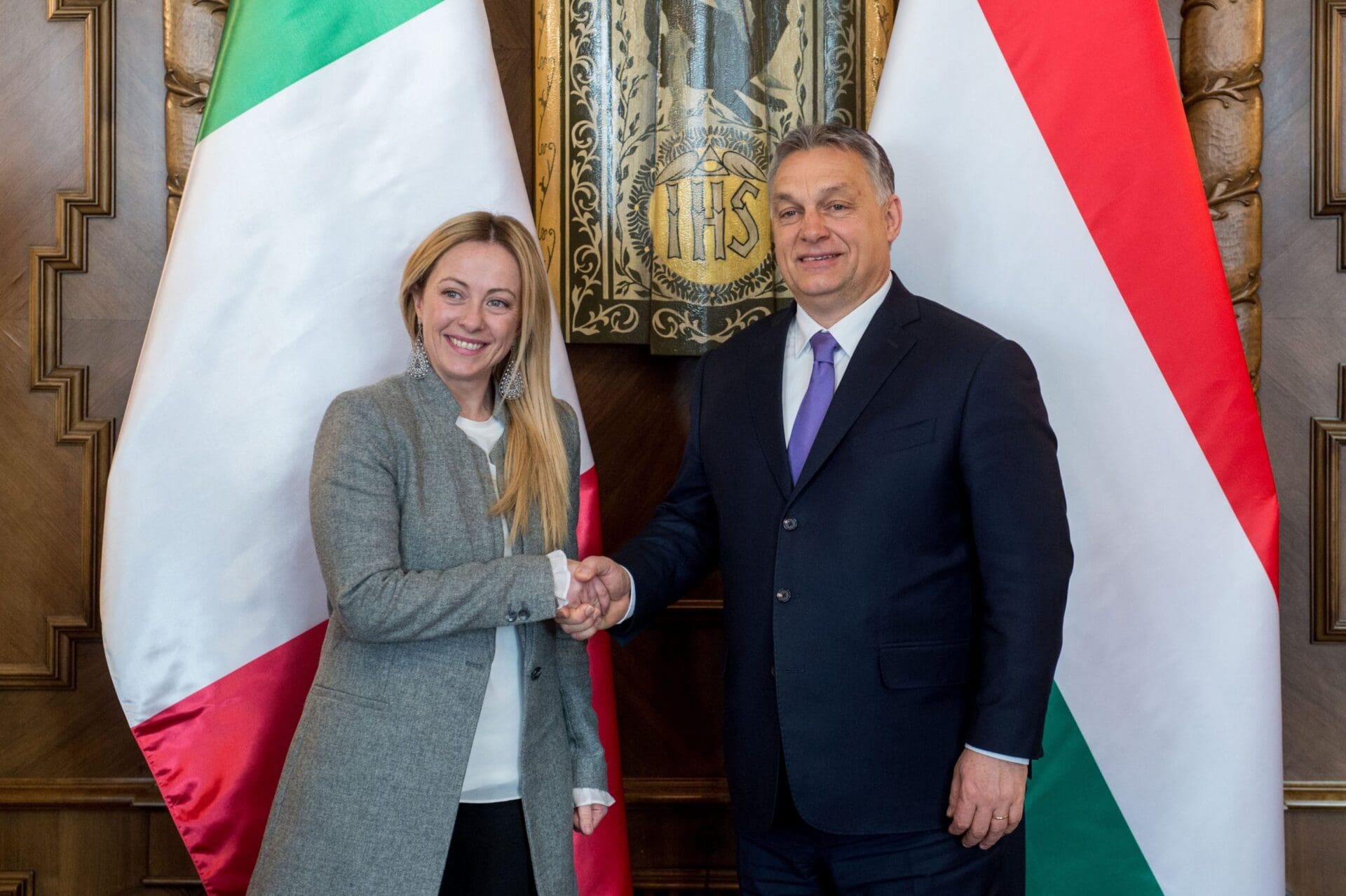

Orbán and Meloni: Shared Vision, Same Mission

Although Salvini has so far been at the forefront of building a new Hungarian-Italian-Polish conservative powerhouse, Meloni’s victory could rebalance the situation. This new scenario is unlikely to affect Orbán, since his relationship with the new Italian prime minister is long-standing.

On 23 October 2020, when Francesco Pingitore—known for his song ‘Avanti Ragazzi di Buda’ composed in 1966 on the tenth anniversary of the 1956 Revolution and Freedom Fight—was awarded the Hungarian Cross of the Order of Merit in Budapest. The ceremony was also attended by Giorgia Meloni.

‘I always feel at home among Hungarians, not only because of the same-coloured national flag and strong historical ties, but also because, with Viktor Orbán, we share the same vision and mission for Europe, and this is also embodied in the Hungarian national holiday of 23 October. The Europe that has been created by the struggle of so many to defend borders, to safeguard European roots, identity and values must prevail today,’ Meloni nailed down after the ceremony.

Right-wing parties should firmly represent ‘many millions of European citizens that believe in the traditional family model, a European community based on strong nations, as well as shared cultural and religious roots’—this is what Orbán and Meloni firmly agreed on meeting in Brussels in June 2021. In August 2021 Orbán met again with Giorgia Meloni in Rome to discuss the situation of the European right and the renewed threat of migration. The party leaders stated that their common goal is to make the right the biggest political force in Europe again.

‘More than well-deserved victory. Congratulations!’ posted Viktor Orbán on his Facebook after the victory of the centre-right. The Hungarian PM also wrote to Meloni that the success of the Fratelli d’Italia party is a victory of the values which ‘constitute the very basis of our cooperation and friendship’.

Budapest-Warsaw-Rome

In April 2022 after his election victory earlier that month, Hungary’s prime minister broke a tradition that had existed since 2010, as he chose to visit Italy first and not Poland. This indicates, on the one hand, that Orbán has not given up on building the European conservative bridge, in which he has given Italy a very prominent place. On the other hand, it also signalled a temporary estrangement between Budapest and Warsaw.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, relations between the Visegrad countries and between Hungary and Poland, in particular, have eroded apace. Although different views on Russia have always been present among V4 countries, the major disagreements between Hungary and Poland arose over diverse attitudes to the war, arms shipments to Ukraine and Russian energy. Thus, by the end of this spring, relationships between the V4, including Hungary and Poland, seemed to have turned hopelessly strained, with substantive cooperation stalled.

In the meantime, Warsaw has been in continuous discussion with the European Commission on the country’s recovery and resilience plan to finally receive €23.9 billion in grants and €11.5 billion in loans under the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). By the end of August, it was clear that despite the EU Commission’s and then the Council’s endorsement of the Polish recovery plan and Poland’s rule of law reforms, Warsaw will not see RRF money any time soon. The deception of Brussels—as leading Polish politicians described—made Warsaw dust off the old playbook and return firmly to its friends and allies again. It means that Warsaw could once again side with Budapest in the face of Brussels while seeking to revitalise the regional V4 cooperation. ‘The Polish and Hungarian positions are very much in line, so I want to cooperate as closely as possible within the Visegrád Group on all issues affecting our region,’ Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki highlighted to salon24.

Thus, the voices that have buried the Polish-Hungarian friendship and predicted the end of the strategic cooperation between the two countries seem to have been misguided. And with the victory of Giorgia Meloni and the rise of the centre-right in Italy, Warsaw and Budapest have gained another important ally in pursuing Europe’s conservative renaissance.