This article was published in our print edition’s Special Issue on the European Union.

As European parliamentary elections loom in June of this year, the battle between ‘federalists’ and ‘sovereigntists’ in the EU is heating up. And although Europe has many distinct political features, as a patchwork of nations with a diverse and complex history, its political discourse often focuses on imitating elements of American political development that may or may not map on to European realities. Recently, this tendency has focused on the expectation of a ‘Hamiltonian moment’ in the development of Europe—a moment at which real political union is catalysed in response to a financial crisis. This ‘Hamilton envy’ is, however, symptomatic of a larger dysfunction, the absence of a political view that could identify and respond to current political challenges.

Before we get any further into what Europe’s ‘Hamiltonian moment’ could be, let us stop and ask: why are European elites using a framework borrowed from American political history? The United States followed a distinct path of political development based in the common culture of its thirteen founding states, and fortuitous circumstances that enabled the citizens of those states to empower a national layer of government. As the United States became the dominant Western and then global power, many European politicians came to envy American political strength and imagine that a similarly constructed European ‘superstate’ would invigorate the otherwise fractious European political climate.

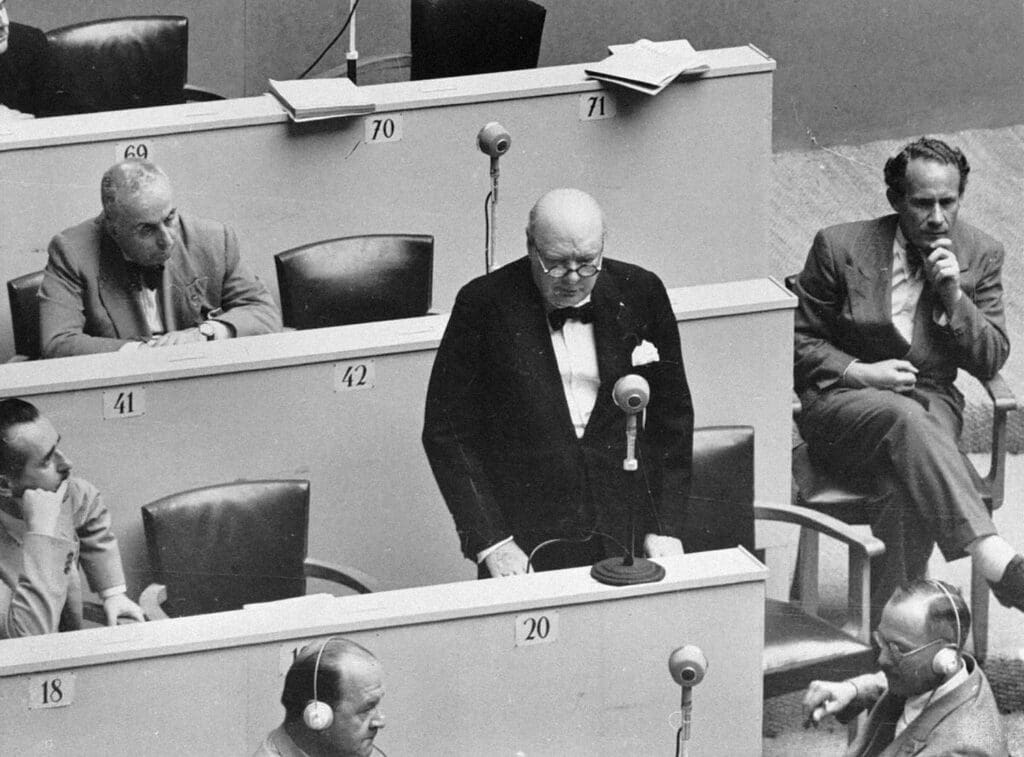

This envy is not new. Victor Hugo gave a speech calling for the creation of a ‘United States of Europe’ in 1849, nearly a century before Winston Churchill’s more famous 1946 speech in Zurich.1 After the Second World War, as negotiations over what would eventually become the EU took off, European federalists relied on the American political experience as a guide, though their efforts to create a similar federalist system largely failed. The quest for a European constitution eventually culminated in the 2001 creation of the European Convention, modelled on the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia and dubbed the EU’s ‘Madisonian moment’. The convention’s Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe (TCE) was rejected by France and the Netherlands in national referenda, however, and the EU had to abandon the idea of a single codified constitution.

The TCE’s failure is not surprising, and support for a federalist Europe is not particularly strong. Relinquishing sovereignty is much more difficult for the diverse nation states within the EU, all of which have long, complex histories, than it was for the newly formed states in America after independence. In 1980, Altiero Spinelli, one of the founding fathers of the EU and perhaps the most prominent European federalist, created the ‘Crocodile Club’ in the European Parliament to advocate for his ideas.2 The modern-day Spinelli group, however, only has 59 MEPs, a small portion of the 705 in total. This share is expected to further decline after the 2024 EP elections.

‘[Europe’s] political discourse often focuses on imitating elements of American political development that may or may not map on to European realities’

Despite the failures of the European federalist movement to overcome political divisions, European leaders and commenters have continued to draw parallels with the American example. Yet when leaders are focused on repeating some element of another country’s political success, their decisions can become distorted—and the results may not bring the same success. This tendency has come about even within the United States itself, as for example when conservatives focus too much on ‘returning to the founders’ at the expense of thinking politically about current problems. In the case of Europe, questing after such political comparisons can lead to an even more tragic result. Whereas the United States federalized during its early growth, the EU is trying to do so in order to paper over its political and economic decline.

What Is the EU’s ‘Hamiltonian Moment’?

In European political discourse, talk of a ‘Hamiltonian moment’ by which the EU could assume greater power has returned, particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. In May 2020, just as the pandemic was reaching its initial heights, France and Germany proposed a €500 billion European coronavirus recovery fund, which would raise money by issuing common EU debt and then make grants to member states. This development was particularly significant in view of the historical differences between Paris and Berlin over the EU’s fiscal policy and risk sharing in the eurozone.

The Merkel–Macron initiative was seen by some as a parallel to the Compromise of 1790, by which the US federal government assumed state debts and became the chief taxing authority. Alexander Hamilton, who was the first Secretary of the Treasury at the time, argued for the move as a way of paying the debts that had been incurred by states during the Revolutionary War (1775–1783) and establishing good public credit abroad. The Compromise of 1790 was a pivotal moment in American political history and contributed to the authority and prestige of the new federal government.

When European elites long for a ‘Hamiltonian moment’, they imagine that a particular common financial necessity could be the spark that brings about a common political framework as well—hence the continuous return of talk of the ‘Hamiltonian moment’ in discussing the EU’s attempts to deal with the eurozone crisis. The phrase was first coined by Paul Volcker, chairman of the Economic Recovery Advisory Board during the first Obama administration.3 Volcker believed that, in light of the ongoing financial crisis, EU members had reached a moment of crisis similar to the one experienced by the US states in 1790, but the EU had no figure like Alexander Hamilton to unite them. The term was only adopted by EU officials after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

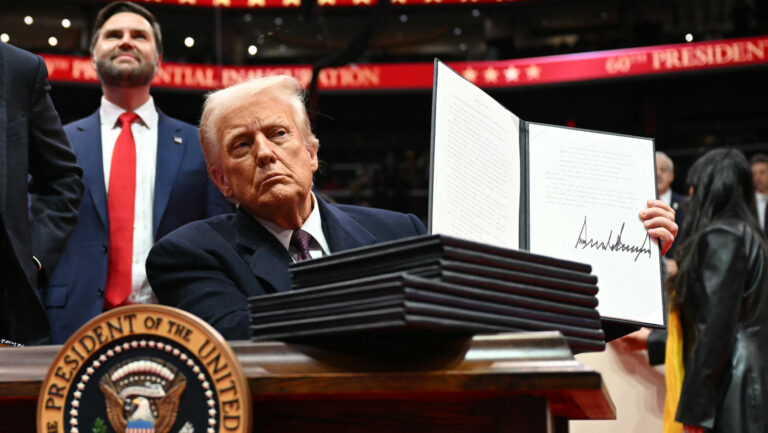

In the 2020 context, the most notable figure to refer to the COVID recovery fund as the EU’s ‘Hamiltonian moment’ was Germany’s then finance minister, Olaf Scholz.4 Since the establishment of the COVID recovery fund would depend on the issuance of common European debt, the hope was that it would be the first step toward a European fiscal union and, perhaps, a closer political union as well. The proposal also included plans for raising the European Commission budget from 1.2 to 2 per cent of EU gross income, which meant increasing tax revenues and customs duties to generate more income—a step towards expanding the EU’s taxation powers.

Yet in other respects, the Merkel–Macron proposal was very far from the Hamiltonian plan. In particular, the EU was not going to assume any debts from member states. Instead, the idea was for the EU to act more like the World Bank—borrowing against its AAA credit rating and passing this borrowed credit along to members in the form of grants. Joint loans would allow members with lower credit ratings to borrow on more favourable terms. Merkel stressed that the plan would be a one-off measure to tackle the COVID-19 crisis.

The political context of the COVID recovery plan was also not very auspicious in terms of aiming at ‘Hamiltonian’ results. Indeed, in retrospect, linking the ‘Hamiltonian moment’ to the COVID pandemic response reflects the poverty of contemporary European political thinking. The early American republic had emerged from a shared war of independence that created the beginnings of a shared identity. The initial loose post-war governing framework, the Articles of Confederation (1781), had left the thirteen states poorly coordinated and underfunded. Whereas the governing body created by the Articles of Confederation was essentially a form of delegated power, the new federal government of the US Constitution (1789) drew its power from the American people as a whole. In other words, America’s ‘Hamiltonian moment’ was preceded by a unique political unification that preserved state-level government while establishing a unified national government for particular purposes.

In the European context, the federalists who hope for Brussels’s expanded authority seem to want to put the cart before the horse. They hope that a financial necessity could lead to political unification. But if recent history is any guide, financial crises in Europe tend to have the opposite effect, encouraging recrimination among member states. That the COVID pandemic was thought to be a moment in which the leadership of the European political class could shine is also a rather sad commentary on European political imagination. While the pandemic drew a strong response from governments, ordinary people simply wanted to be safe and, eventually, to have the restrictions lifted. The political valence of the COVID pandemic has not lasted, either as a credit to political leaders or (for those dissatisfied with the pandemic response) as a criticism of them. Meanwhile, European leaders have not only not outlined a comparable political force that could motivate political union, but they have been reluctant to include elements that would help cement a shared European identity. Over centuries of European history, Christianity provided a framework for the differing nations to relate to one another and speak in a common language. However, European leaders have been reluctant even to name Christianity as a shared element of European heritage.

‘Recently, this tendency has focused on the expectation of a “Hamiltonian moment” in the development of Europe—a moment at which real political union is catalyzed in response to a financial crisis’

Not only did the COVID recovery fund not occasion a new political unification in Europe, but in many ways it did the opposite, as the distribution of funds quickly became politicized in a divisive way. After the initial proposals of spring 2020, in July of that year EU leaders agreed to a €750 billion recovery fund dubbed ‘Next Generation EU’ (NGEU) as well as at least one new EU tax on non-recycled plastic waste. In the plan’s final form, only about half of funds were issued as grants, while the other half were given to member states as cheap loans. To obtain the funds, countries were required to create investment plans and undertake various reforms. Hungary and Poland initially threatened to veto NGEU due to their opposition to EU funds being linked to national reforms.

The COVID recovery fund’s politicization, particularly vis-à-vis Hungary, has also shown the hollowness of the EU’s desire for a ‘Hamiltonian moment’ to emerge from the recovery fund. EU member states were required to submit national recovery and resilience plans to receive funds, and the first of these plans were approved beginning in July 2021. Hungary’s plan was approved last, in December 2022, and the European Commission said that Hungary would not receive any payments until judicial reforms and anti-corruption measures were implemented. Of the €20 billion in grants and low-interest loans that had been frozen, about half was unfrozen in December 2023, but the rest remains frozen.

‘When European elites long for a “Hamiltonian moment”, they imagine that a particular common financial necessity could be the spark that brings about a common political framework’

According to The Economist, the recovery fund succeeded in preventing another eurozone crisis, provided EU member governments with additional funds, accelerated digitization and green transition projects, and funded politically difficult reforms.5 However, the programme has not brought fiscal union closer, and if anything has uncovered additional political tensions within the bloc. As the Financial Times pointed out in a February analysis of the plan’s implementation, not only Budapest and Warsaw but Western capitals also underwent policy changes in order to access the recovery funds. Yet to date, only somewhat more than a third of the funds have been disbursed. Of the funds that were disbursed, at least €600 million was embezzled through fictitious companies.6 So, while the fund was effective in forestalling the worst effects of the pandemic, it has been weaker in fostering the industrial growth that it promised.7

New Moves Toward Issuing Joint Debt

While the issuance of joint EU debt was meant to be a one-off measure to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic, some EU members proposed repeating the move in 2022 to deal with the emerging energy crisis, though the plan never came to fruition. Now France is pushing for increased EU defence spending, given the security situation created by Russia, and is looking to partially fund these expenditures by issuing joint EU debt. Leaders from Spain, Estonia, and Belgium have already announced their support. Defence spending was also discussed in further detail at the EU leaders’ summit in March, and leaders agreed to receive ‘all options for mobilizing funding’ in a report in June.8

The idea of so-called eurobonds is not new. The discussion has been going on since the 1950s, although the idea only gained serious traction in 2011/12 as the EU considered issuing joint debt in response to the ongoing challenges of the financial crisis. But issuing defence bonds—eurobonds specifically designed to support defence spending—remains taboo. The EU’s founding treaties have long been interpreted as prohibiting the use of the EU budget for military purposes, although the European Commission has asked its team of lawyers to reassess that interpretation.9

Any proposal for a defence-oriented common debt structure will face opposition. The ‘Frugal Five’—Austria, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, and Sweden—oppose issuing joint EU debt because they believe it will disadvantage wealthier EU members, who will end up paying more for their debt. Other countries oppose the move because they see it as a step toward establishing fiscal union, which would limit the sovereignty of EU member states over their financial matters. Others point to the failures of NGEU and worry that taking on hundreds of billions of euros in debt will only negatively impact future generations, who will likely have their own challenges and crises to manage. It does not help that the cost of joint borrowing continues to rise, driven by economic stagnation and high levels of inflation across Europe. It seems unlikely that a proposal for issuing more joint debt will succeed. Member states are already working on other initiatives to fund defence spending, however, such as amending the European Investment Bank’s mandate or (more problematically) using profits from frozen Russian assets.

The EU coronavirus recovery plan was a far cry from Hamilton’s plan for the US federal government to assume state debts and become the chief borrowing and taxing authority. Issuing joint EU debt to mitigate the effects of the pandemic did not mark the beginning of a European fiscal union, and the reluctance among EU leaders to repeat the move proves that deep divisions remain in the political climate in Europe.

As Europe has entered a period of economic stagnation and even industrial decline, it is bitterly ironic to evoke the strategies of the rapidly growing early American republic. Without a coherent European economic strategy, merging debt issuance is likely to bring out the worst features of Brussels’s approach toward member states. After the halting, politicized experience of the COVID recovery fund, member states should not begin bankrolling unaccountable debt schemes that cause further political alienation.

In the end, the EU is far from becoming a ‘United States of Europe’. Instead of focusing on drawing romantic historical parallels, European leaders must come to terms with reality and focus on addressing Europe’s real problem: a crisis of competency stemming from a European leadership that can only dream of recreating someone else’s visions.

‘As Europe has entered a period of economic stagnation and even industrial decline, it is bitterly ironic to evoke the strategies of the rapidly growing early American republic’

NOTES

1 Agnès Poirier, ‘Victor Hugo’s Ideal of Europe’, Engelsberg Ideas (20 August 2021), https://engelsbergideas.com/essays/victor-hugos-ideal-of-europe/; Winston Churchill, ‘Speech at the University of Zurich, 19 September 1946’, https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/speeches/1946-1963-elder-statesman/united-states-of-europe/.

2 Pier Virgilio Dastoli, ‘Altiero Spinelli and the Crocodile Club: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow’, The New Federalist (29 August 2020), www.thenewfederalist.eu/altiero-spinelli-and-the-crocodile-club-yesterday-today-and-tomorrow.

3 Noted by Alan Wheatley, ‘What Europe Can Learn from Alexander Hamilton’, Reuters (18 January 2012), www.reuters.com/article/eurozone-hamilton-idINDEE80H01A20120118/.

4 Sam Whimster, ‘What Is a Hamiltonian Moment?’, Global Policy Institute (5 June 2020), https://gpilondon.com/publications/what-is-a-hamilton-moment.

5 ‘The EU’s Covid-19 Recovery Fund Has Worked, But Not as Intended’, The Economist (15 February 2024), www.economist.com/europe/2024/02/15/the-eus-covid-19-recovery-fund-has-worked-but-not-as-intended.

6 Hannah Roberts and Elisa Braun, ‘Lamborghini and Rolexes Seized in Massive EU Police Raid over €600M Covid Fraud’, Politico (4 April 2024), www.politico.eu/article/police-fraud-financial-unit-arrests-23-suspects-600-million-fraud-eu-covid-recovery-fund/.

7 Paola Tamma, ‘Is the EU’s Covid Recovery Fund Failing?’, Financial Times (20 February 2024), www.ft.com/content/d4fb8828-87e9-4509-b2a4-852728f39064.

8 ‘Conclusions of the European Council Meeting, 21/22 March 2024’, www.consilium.europa.eu/media/70880/euco-conclusions-2122032024.pdf.

9 Henry Foy, ‘Why the Ban on Using EU Funds for Arms Could Become More Flexible,’ Financial Times (25 March 2024), www.ft.com/content/8b726600-ef07-4c97-be58-9e22b38d0dee.