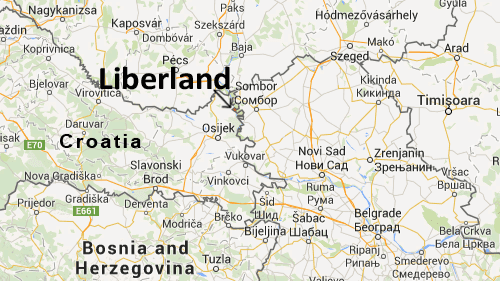

Liberland is an unrecognized microstate set up on unclaimed territory between Croatia and Serbia. Is it time for Hungary to start taking its new neighbour seriously?

Starting from Budapest, you can hop on a boat, travel roughly 190 kilometres to the south down the Danube, and you’ll find yourself in a country that is not on any map. It is located upon land that belongs neither to Hungary, nor to Serbia and Croatia, whose relationship with this territory is worth an article in its own right. Straddling the river Danube that separates it from the mainland is an obscure and relatively unknown island, whose territory is claimed by an unrecognized microstate that is taking steps to assert its authority we had better pay attention to.

That state is Liberland: one of the youngest, smallest, and least recognized countries on planet earth.

Its existence was declared in April of 2015: the culmination of years of work by a small and loosely affiliated group of activists, utopians, and tech-savvy Libertarians

to actualize their ambitions of having a common physical space to practice what they had preached. It would be a place where freedom—understood through the logic of the Non-Aggression Principle (NAP)—would reign supreme, and where a community formed through the principles of voluntary association and collective consent could one day live and prosper. This was a vision that, for all its Pollyannish optimism, was able to mobilize a group of radically diverse individuals around the world, coming from all walks of life, into what may well be the first nation in history united not by geography or ancestry, but by a consensual commitment to human freedom.

Mass movements, as American philosopher Eric Hoffer described, can be found everywhere, for every reason. Most coalesce and disintegrate so rapidly that the world scarcely has time to take note of their short-lived existence. What distinguishes successful movements from unsuccessful ones, he argued, is the presence and competence of leaders; figures who either demand or are forced to take on the mantle of responsibility for guiding the developmental trajectory of a community that has united around a specific cause. In the case of Liberland, that leader is Vít Jedlička:

a man whose name has become inseparably tied to Liberland and its somewhat eclectic brand as a self-declared independent state.

Born in then-Czechoslovakia in 1983, Jedlička’s career can be divided into two parts: what came before Liberland, and everything afterward. Jedlička was the principal founder and brand ambassador of Liberland as an independent state in 2015—a year which also marks his inauguration as the country’s first president, in line with preliminary (pre-election) arrangements stipulated by the Liberland constitution. Jedlička’s role as the effective figurehead and legally authorized president of Liberland has remained unchanged in the 8-some years that have since passed; but so too have the energetic attitudes of the Liberland leadership toward their project and its long-term prospects, and those who have stuck around show no signs of slowing, Jedlička being the most prominent among them.

Having spoken to President Jedlička on the phone over the course of my initial investigation into Liberland, I felt that I was dealing with a man who was easy to talk to, but hard to figure out. Libertarianism, a cold, ruthless, cutthroat let-live and let-die ideology (as it is commonly construed), is rarely afforded authentic representation through the lens of Western mainstream media channels. Just so too for its figureheads, a category to which President Jedlička now most certainly belongs, but this leaves the very few who have even heard of Liberland deprived of answers to the more interesting questions that could be asked about this nation-building project. Liberland has a government, it has a constitution, it has laws, and it has governmental ministers—including ministers of law, and finance—who take their jobs extremely seriously. It has an e-residency scheme based explicitly on the model first deployed in Estonia, where the government accepts the legal rights of those who do not actually reside in the country to become functional residents in legal and economic terms for the purpose of facilitating business creation, operation, and investment. It has embassies with limited recognition in countries around the world, even while remaining entirely ignored by the UN—a supranational body that Liberland’s leadership, I was informed, intends to build ties with. We might pause and ask ourselves: what on earth are we looking at here? Is it just another vanity project by some charismatic but manipulative leader, is it a deluded community united only by ambition and rejection of the mainstream, or is it an actual state after all?

Whatever Liberland is, or will become, it’s interesting to consider how Jedlička manage to take a group of disaggregated freedom-loving idealists, and shepherd them into the establishment of a supposedly sovereign state? What kind of people were involved in Liberland before Liberland existed, and why did they accept Jedlička’s authority and support his leadership?

How did we go from a fantastical pipedream existing only on the internet to a self-described sovereign state with a working government,

a passport service, and over 800,000 approved applications for e-residency status, all within the span of just ten years? At the present moment in time, all such questions are met by enthusiastic and informative answers when posed to Liberland itself via official channels—yet there is no overarching narrative that clearly emerges from these disaggregated bytes of information. It seems inevitable that the Liberland project (a project involving networks, ideology, finance, technology, and of course, professional LARPing) will be fertile ground for a remarkable story sometime in the near future; perhaps even a Hollywood biopic. But as an unfinished story, Liberland is not easy to write about—not at all.

The idea of founding a country from scratch in order to establish a homeland for a nation that does not exist yet is an act that would be seen by most as patently insane. Excluding breakoff republics like the Donetsk People’s Republic or illegal occupations like Turkish Cyprus, the youngest five countries in the world are now South Sudan, Kosovo, Montenegro, East Timor, and Palau. All of these split off from existing state entities, rather than being founded on unclaimed land, and all but one were founded upon the rationale of ethnic self-determination, Montenegro being the exception. Setting aside momentarily the significance of two out of these five states being carved out from formerly Serbian territory (the same Serbia with which Liberland ostensibly shares a border), it is clear that the declaration of a new state based on—of all things—Libertarian idealism is not an act for which there is a recent historical precedent.

But looking a little further into the past,

it should be clear to all that there is indeed such precedent; and a very notable one, in fact.

The United States of America, at its founding, was the state closest in its constitution and ideology to modern-day libertarian values in the entire world. The ideals of the early American republic are a strong influence—an acknowledged one—on the Liberland project. Liberland was founded as an independent state on 13 April 2015, in commemoration of Thomas Jefferson’s birthday, as a testament to this influence. How this will play out in the long term has yet to be seen.

What has been made clear already through is that Liberland is no small-time pipe dream. The microstate has been visited and covered in articles by mainstream outlets like CNN, and more recently has also been documented by popular YouTubers like Niko Omilana, in a video that received over eight million views and 390,000 likes. The fact of the matter is that Liberland exists, and it appears to be here to stay. How Hungary responds to this is yet to be seen.