7 February 1992 marks the day when the finance and foreign ministers of Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom sat down to create the European Union—more or less in in the form as we know it today.

The adoption of the Maastricht Treaty was not without problems. Originally, the document stipulated that it would enter into force on 1 January 1993, but this date had to be moved to November. Difficulties mostly arose because the constitutions of many member states had to be amended for the Maastricht Treaty to come into effect.

The treaty, to which 17 protocols and 33 declarations were also attached, fits into the overall integration project that the founding fathers of the bloc prescribed at the beginning. As is known, the Treaty of Rome (1957) states that the signatories are ‘determined to lay the foundations of an ever-closer union among the peoples of Europe’. The Maastricht Treaty certainly introduced progressive elements pointing in that direction.

Ratification Process Overshadowed by Heated Disputes

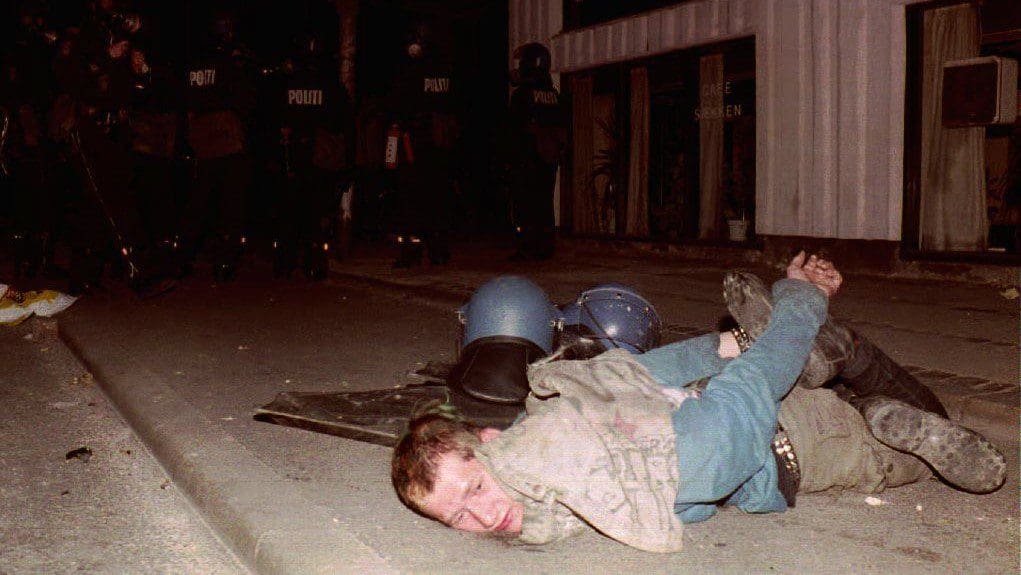

The ratification process of the Treaty generated sharp political debates in several member states. Denmark rejected the treaty on 2 June 1992. For a while, it seemed that the project would fail simply because of the Danish ‘no’, but in the end the Council decided to leave open the possibility for Denmark to join the treaty at a later date.

Although the campaign in favour of the Maastricht Treaty in Ireland was mainly about its economic benefits, the Irish government seemed reluctant initially. The debate around Maastricht was at first glance unrelated to the treaty which was of apparently of purely economic natures. However, Ireland at the time rejected abortion on moral grounds, while the European Community considered the performing of abortions a service—meaning that in principle, restricting abortion would have conflicted with the principle of the freedom to provide services. That is why the Irish government added a protocol to the Maastricht Treaty that gave Ireland an exemption in this regard. Later on, a referendum was held in Ireland on the issue, with 69.05 percent of the votes supporting adoption of the treaty.

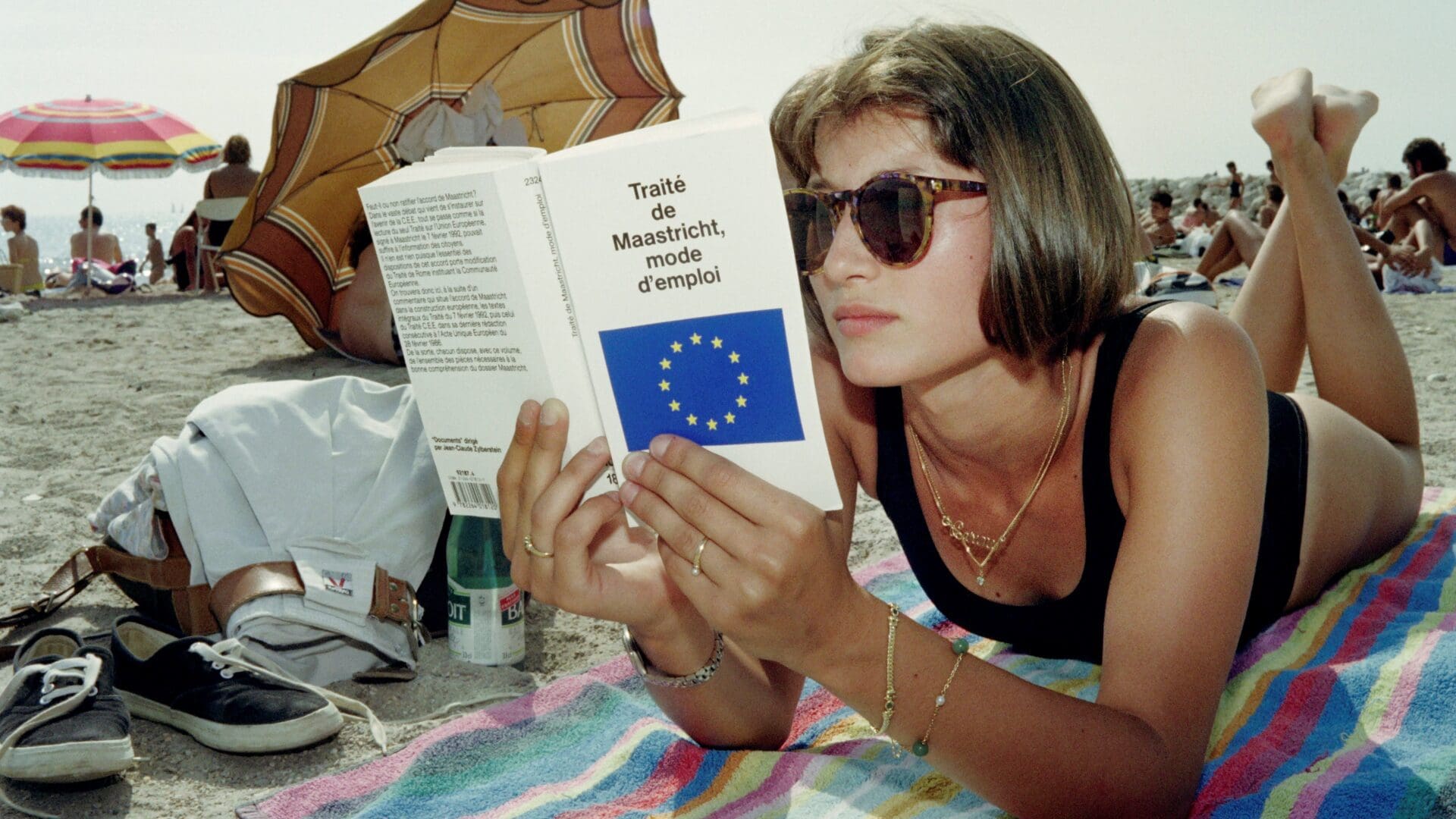

In France, society was divided about how successful the European project would be; many feared that Germany’s supremacy would strengthen, and heated disputes also arose on the French participation in the ongoing integration—Communists, Gaullists and Le Pen’s Nationalists alike opposed ratification.

Finally, the issue was decided by referendum in France as well, however, only 51.05 per cent of voters voted in favour of the treaty. Although the referendum was valid and successful, many suggested that only a ‘handful’ of French people decided on its result.

In Germany, it was necessary to wait for the decision of the Constitutional Court before the Maastricht Treaty was given the green light. The body finally found that the Maastricht Treaty is in line with the German Constitution, because Germany decided to transfer only a part of its sovereignty at the time of accession—so it was still the sole right of the Bundestag to decide which powers are to be transferred to the European Community (Union) and which are to be kept. Another guardian of the German sovereignty is the Constitutional Court itself which is authorised to review the acts of the Bundestag.

What is the Pillar System We All Learnt About in Secondary School?

The ‘pillar’ model introduced by the treaty may also be familiar from secondary school curricula. According to policies, this solution implements a system of division of powers between the member states and the supranational level.

Under the first pillar, the treaties on the European Economic Community, the European Coal and Steel Community, and EURATOM, and their amendments were included. This pillar typically enables community-level decision-making in these areas. The biggest innovation of the first pillar can be considered the introduction of the Economic and Monetary Union (in connection with the latter, the United Kingdom, which has since left the EU, immediately exercised its opt-out option).

The second pillar establishes the Common Foreign and Security Policy. It should be noted that the Maastricht Treaty defines these fields of policymaking quite broadly. Safeguarding the ‘common values, fundamental interests and independence of the Union’ and ‘to develop and consolidate democracy and the rule of law, and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms’ – just to name a few examples that are decisive in nowadays’ disputes within the EU.

The second pillar imposes an obligation on the member states to coordinate their policies, adopt common positions, and represent these in all international organisations. Thus it primarily focuses on intergovernmental cooperation, thereby increasing the importance of the European Council as the EU’s top body. With regard to this pillar, according to the original intentions, the European Commission is not a proposing party in these fields of legislation, and the EC’s political will is only exercised to a limited extent. In decision-making, the European Parliament participates here with consultative powers.

The third pillar is related to law enforcement and judicial cooperation (Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters). This was already on the agenda from the second half of the 1970s. The so-called Trevi Group, established in 1975, acted in an intergovernmental manner against terrorism and cross-border organised crime, and in 1985 the Schengen Convention was also signed for similar purposes. However, a breakthrough was indeed brought by the Maastricht Treaty, which resulted in the deepening of integration in this area as well.

As a result, the third pillar includes asylum policy, external border control, immigration policy, the fight against drug trafficking, the fight against international fraud, judicial cooperation in criminal and civil matters, as well as customs and police cooperation.

Since these areas directly affect the concept of state sovereignty, cooperation in this regard also remained at the intergovernmental level. The European Commission’s power to initiate legislation is theoretically limited, and the decisions are made by the Council by consensus. The right of control of the European Parliament is limited under the Maastricht Treaty.

Subsidiarity — An Undervalued Christian Concept

One of the greatest—yet most underrated—achievements of the Maastricht Treaty was the introduction of the principle of subsidiarity. In principle, this means that a decision must be made at the community level only if decision-making is less possible or effective at the national level.

Article 3b of the Maastricht Treaty states:

’In areas which do not fall within its exclusive competence, the Community shall take action, in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity, only if and in so far as the objectives of the proposed action cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States and can therefore, by reason of the scale or effects of the proposed action, be better achieved by the Community.’

Since the beginning of the 20th century, there has been not only a legislative but also a cultural demand for the enforcement of the principle of subsidiarity in Europe. Pope Pius XI in his social encyclical of 1931 states that ‘Just as it is gravely wrong to take from individuals what they can accomplish by their own initiative and industry and give it to the community, so also it is an injustice and at the same time a grave evil and disturbance of right order to assign to a greater and higher association what lesser and subordinate organizations can do.’ (Quadragesimo Anno)

Although this principle—due to its vagueness—seems elusive, in the case of The Queen v. Secretary of State for Health, ex parte British American Tobacco (Investments) Ltd. and Imperial Tobacco Ltd., the European Court of Justice attempted to make the principle of subsidiarity legally enforceable. The ECJ concluded that it leads to the invalidity of a legal act if the enacting authorities fail to take into account the principle of subsidiarity and proportionality.

However, according to its critics, the three decades of the Maastricht Treaty taught us that the principle of subsidiarity is respected at the level of gestures at most towards political communities that deem state sovereignty a value to preserve.

As Tymotheusz Zych, an analyst of the Italian think tank The Machiavelli Center for Political and Strategic Studies points out, during the decades of European integration, the jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European Union has broadened the powers of the EU authorities to encompass more and more policies—including those that would otherwise belong to the Member States on the basis of the principle of subsidiarity.

According to critics, all of this leads to the ‘inflation’ of legislation in the European Union—which certainly involves the erosion of the rule of law and the values attached to it (e.g. legal certainty).

At the same time, the principle of subsidiarity is becoming less and less important not only because of excessive centralisation—the opposite is also true. The case of the Minority SafePack demonstrates that the authorities of the European Union ignore this principle even when central regulation is necessary.

As the president of the Federal Union of European Nationalities (FUEN) Loránt Vincze stated in a Hungarian Conservative interview, the European Commission and the ECJ live in a ‘parallel reality’. By that he means, that a verdict of ECJ stated that the Commission is right, and indeed no further steps are necessary – even though minorities in many regions face assimilation and language loss within the EU.