‘Abdicating democracy can come about in two ways, either through an internal dictatorship that concentrates all powers in a providential man, or through the delegation of those powers to an external authority, which will in fact exert political power but in the guise of technical expertise. For, in the name of a healthy economy, one can easily impose a monetary, budgetary and social policy, which add up to a “political agenda”, in the broadest sense of the term, both at national and international level.’

These are not the words of a ‘populist’ or a ‘nationalist’ and still less a ‘reactionary’. They were spoken by Pierre Mendès France, the centre-left French Prime Minister between 1954 and 1955, a politician whose probity and moderation have made him a widely respected figure in France. He uttered those words in 1957, during a parliamentary debate on the signing of the Treaty of Rome, and the question it raises is clearly no less pertinent sixty years later. On the contrary, after the adoption of the European Recovery Plan in June 2020, which strengthens the powers of the EU and mutualizes debts, this question remains today more relevant than ever.

Indeed, the Recovery Plan is an unprecedented response to an unprecedented crisis. It also exemplifies the dilemmas the Union faces in the most turbulent period of its short history. Fast and salutary response for some, federalization through the back door and strengthening of the hold of Brussels on national competences for others. Moreover, despite (or because of) the pandemic, an EU at its lowest has made a qualitative leap and gained powers that it had been eyeing for ten years. And this, after a decade of successive crises which have weakened it and alienated it from a large part of the citizens, not to mention the increased tensions between member states. Weaker and more powerful, maligned and solicited, all eyes (from the kindest to the most suspicious) have turned to the EU to thwart the economic and social tsunami triggered by COVID-19.

In addition, this crisis only adds to many other challenges which relate to the question, increasingly present in the public debate, of ‘European sovereignty’, an expression which gets at the heart of the geopolitical weakness of Europe and the admission of decades of both naivety and dogmatism. Because the EU was and is naive and dogmatic, both internally and externally, this triggers internal tensions that prevent it from meeting pressing challenges. Some European circles are even messianic, brandishing ‘European values’ like sacred writ, advocating federalism as the one and only solution to all ills and forgetting that the Union, like any geopolitical construction, is above all a matter of interests. In this very special moment, will the Union be able to demonstrate pragmatism, thus returning to its origins, or will it continue its flight forward towards an unbridled messianism boosted by the binary and simplistic mindset of the digital age?

Do the champions of European geopolitical sovereignty plan to build it to the advantage or to the detriment of the Union’s constituent member states?

The EU at a Crossroads after a Decade of Crises

It is commonplace to assert that the EU is at the crossroads of several paths, that it reinvents itself with each crisis, or that every crisis is an opportunity. But these platitudes must not be allowed to hide the singularity of the present moment, for two reasons.

The first is that Europe has been in a permanent state of acute crisis for more than ten years, more exactly since the Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy, and the subprime mortgage crisis which triggered a huge economic recession in Europe that is still being felt today. The bailout of Greece left the single currency on the ropes, and the Eurozone was on the verge of implosion as a result of the blows suffered during the financial crisis and the ensuing political tensions.

‘Weaker and more powerful, maligned and solicited, all eyes have turned to the EU’

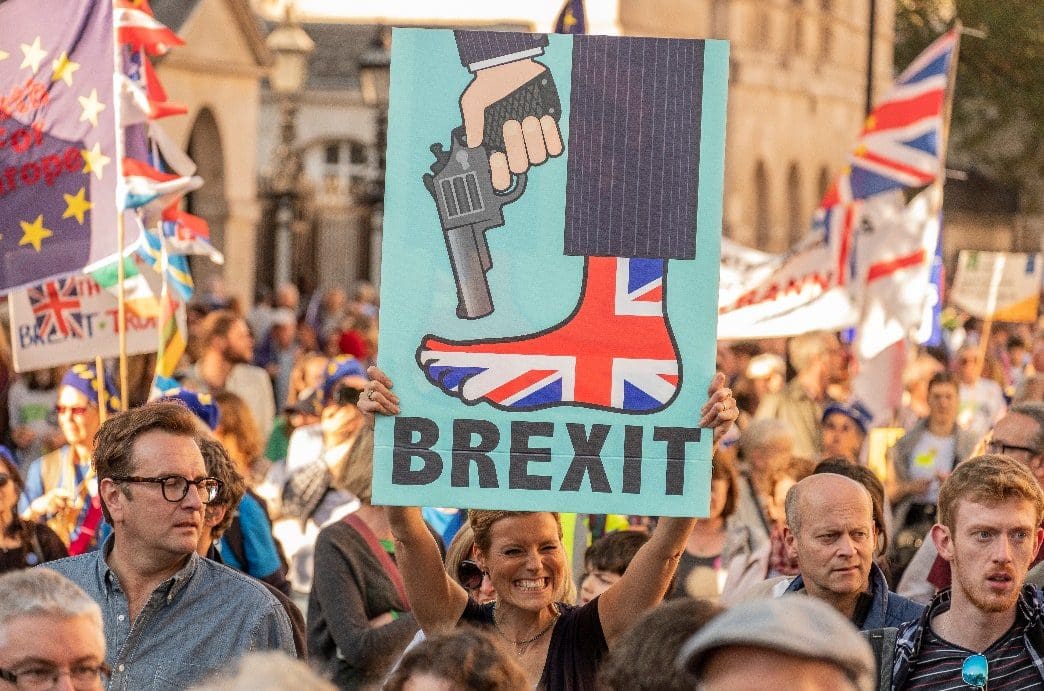

Having barely recovered from this ordeal which had left it exhausted, the Union was dragged into a migratory crisis in 2015, which split the continent as never before, and generated tensions the Union was unable to resolve. To this day, the crucial issue of migration remains blocked because of antithetical visions on the matter among member states, and also between institutions. A stalemate. Besides all this came the wave of jihadist attacks in Western Europe and finally Brexit, a real cold shower for the Brussels elites who were not expecting this outcome. This was followed by painful and laborious talks aimed at avoiding a hard Brexit.

We are therefore talking about a cursed decade, a decennius horribilis during which the EU has been battered on many fronts and left worn and weakened. Even though citizens’ confidence has been on the rise recently, the gap between the EU and those it represents has widened over the past decade, and the Union’s image has been seriously damaged. Not to mention the tensions and mistrust between member states (North / South but especially East / West) which undermine the internal cohesion of the Union and damage the reputation of its institutions. The EU is exhausted and weakened.

Added to all this are structural challenges that are making a dramatic entry into the political agenda at all levels. First of all, geopolitics, which is making a comeback with a threateningly efficient China mounting an open challenge to American hegemony. Then there is the question of European defence and its absolute dependence on NATO, which according to French President Macron is ‘brain dead’. Another issue is the digital revolution of which Europe has missed the first train and which conceals a nearly dystopian reality of censorship, individual alienation and commercial monopolies behind the cool, attractive facade of social networks. Also, the big data economy and artificial intelligence will have an incalculably disruptive effect on our lives, and we are still struggling to define and anticipate the shape it will take. Perhaps the most hotly debated issues are global warming (a real problem subject to unprecedented political manipulation) and migration, whose current period of abatement is deceptive, and which will return to the fore. Then there are the issues of international trade, the Eastern and Southern neighbourhood of Europe, terrorism, European demographic suicide vs. African demographic timebomb, etc. You name it. These are all subjects on which joint action by the EU would bring real added value if it were supported by all European states without any cracks.

It is therefore a worn-out Union facing major challenges which must undertake a new test. And what a test! The economic and social impact of the pandemic and the repeated lockdowns will be incomparably greater than those of 2008. In Spain, for example, the drop in GDP in 2020 can only be compared to that caused by the Civil War of 1936. This says it all.

But unlike the euro crisis, the EU has this time reacted rather quickly and rather well. In addition to adopting a budget for the next seven years, it has above all elaborated an ambitious Recovery Plan with unprecedented firepower. A historic moment, without any doubt, and a financial tool which will help mitigate the effects of the crisis and which is a lifeline for the states most severely affected by the crisis. Unlike 2008, the Union did not choose austerity but rather revival and flexibility. But it is of course the mutualization of debts (the Commission will borrow on the markets on behalf of the 27 member states) that makes this a historic step. Some even speak of a ‘Hamiltonian moment’ to define this decisive step. Beware of simplistic comparisons (especially those with federalist overtones), but the parallel is not unfounded. Some welcome this step as others fear it.

A founding moment, a point of no return, a qualitative leap? Maybe, but in what direction? A Europe that is inexorably taking the federal path, pushed by COVID? A stronger Europe, in better condition to sail the waters of globalization? Why not, but this approach must still be supported by solid internal cohesion which reflects both the will of citizens and of all member states to move forward in the direction that the crisis and geopolitics seem to have traced on their behalf.

This question naturally leads to another— one which deals with the sovereignty of Europe and of its member states within the EU. Should strengthening the former necessarily be to the detriment of the latter? Or on the contrary, does the consolidation of Europe require an increased influence, a stronger say for states on the future of the Union? More federal or more intergovernmental? What is the best model for the Union to bridge the gap between citizens and an international arena in which it remains a featherweight?

European Sovereignty: Intergovernmental or Federal?

President Macron has revived the notion of ‘Europe as a power’ and ‘European sovereignty’. So much the better. For decades, an ideological and naive Union has totally neglected the geopolitical dimension, preferring mantras on values to strategic analyses. Regarding international trade, for instance, the ideological errors of the Commission were astounding, and Europe had been swamped by the cheap exports of a mercantilist China before the Commission put on the negotiating table the simple notion of reciprocity, normally a core principle in trading relations.

It is reassuring that the very Europhile Macron speaks openly about borders, sovereignty, and power, that he sounds the alarm bells in matters of defence, and expressed loud and clear the degree to which Islamist separatism is a threat to Europe. En même temps, the question of how persists, especially for the European institutions. The latter are increasingly lucid about the final objectives, but remain ideological and detached when thinking about the means to achieve them. Not to mention the providential mentality of a certain elite which thinks more in terms of values than in terms of interests, and perceives the member states more as obstacles in the natural course of history than as the real pillars of the European project. The very idea that a strong Europe requires strong states to sustain it seems inconceivable to them.

It is therefore a safe bet that for some Brussels circles the only response to the geostrategic challenges and the economic crisis is to plough on, adopting the usual Pavlovian reflex of calling for ‘more Europe’ whatever the problem might be.

This is deplorable because this messianic Europe which sees itself more as a moral authority than as a political and technical entity is built upon a triple denial: a denial of its own origins, a denial of some of its cardinal principles, and a denial of political diversity. It takes more than good intentions and slogans to influence the international arena and find a place in between the United States and China. It takes more than ‘shared values’ to recover from a devastating economic crisis. On the contrary, we need flawless internal cohesion and the unanimous will of member states to move in the same direction. What if this messianic and moralizing approach posed a threat to the EU’s cohesion?

A Messianic Europe Based on a Triple Denial

Denial of Origins

The Union’s political and communication agenda has been revolving around ‘common values’, human rights, non-discrimination, the rule of law, and Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) for so long that we forget the very origins of this organization. And in the beginning was … the most prudent pragmatism. Robert Schuman’s declaration of 9 May 1951 is a monument to common sense and political realism. A small-steps approach, consideration of national interests, and mutual trust to lay the foundations for a cooperation based on the political and cultural diversity of its members. Sixty years later, we are a long way from this approach. The Union seems programmed to move perpetually in one direction, no matter what millions of citizens think and vote. Despite citizen mistrust and past political mistakes, the European elites seem to have internalized this laughable metaphor of the EU bicycle that falls if it does not move forward. Citizen disaffection is, they say, at most a result of clumsy communication, but says nothing about the vessel’s course. The citizens would agree … if only they understood!

Of course, the current circumstances are not those of 1951, and a small steps approach would be anachronistic in 2021. But we must not lose sight of the fact that the EU has been in crisis since it decided to take the big leap forward towards a political union and radically change its initial nature. That is to say, since the Treaty of Maastricht marked the end of the Economic Community in 1993, and gave birth to a Union whose unspoken goal seems to be to imitate the United States of America, with intergovernmental conferences following one another. Since then, ratifications by referendum have become headaches, then nightmares, before reaching their climax with the tragicomedy of the European Constitution and the Lisbon Treaty (2005–2008).

With hindsight, it is difficult to deny that the Maastricht Treaty marked the end of the honeymoon between Europe and its citizens, as if the implicit social contract which allowed the rise of the Economic Community had been broken by setting course towards political union. And yet, the course of this Economic Community was well defined, in part because it rested on a balance between the competencies of the Union and those of the member states, and that the vessel moved forward neither too fast nor too far in the eyes of the citizens. Admittedly, the Community was often caricatured as an ‘economic giant and a political dwarf’ but, all in all, on the scale of history, is not a successful single market combined with mechanisms of financial solidarity a brilliant and subtle way to consolidate a continent? Pre-Maastricht Europe disappeared from history, though it was the golden age of European cooperation. In these times of uncertainty and confusion, perhaps leaders should make it a benchmark and learn from it.

Denial of Cardinal Principles

Messianism requires looking ahead, it aims high and does not bother to look around. In so doing, it not only forgets the past, but neglects certain cardinal principles of the Union. For example, the principle of subsidiarity, according to which ‘the Union intervenes only if, and insofar as, the objectives of the envisaged action cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States’. It might be worth assessing in depth the rigour with which European legislators and the Commission apply this principle in their impact assessments, their legislative proposals and their amendments. I doubt it is carefully done, and fear it is more of a formality. I also doubt national parliaments are able to really assume the role of ‘guardians of subsidiarity’ which the Treaty of Lisbon has conferred on them.

But what is lacking above all is a culture of subsidiarity, a reflex of caution that would suffuse not only legislative proposals but also the political positions of European institutions. In their moralizing impulse, the latter tend to develop strategies, action plans or communications on subjects where the Union’s added value is far from obvious.

This criticism applies tel quel to the principle of conferral, according to which ‘the Union shall act only within the limits of the competences conferred upon it by the Member States in the Treaties to attain the objectives set out therein. Competences not conferred upon the Union in the Treaties remain with the Member States.’ A crucial rule which confirms in black and white one of the founding dogmas of the Union: no action without attribution of powers. This is mostly respected in legislative proposals, but not necessarily in other cases. Some infringement proceedings are based on, let us say, imaginative interpretations of EU law, while political initiatives are sometimes launched which ignore the boundaries provided for in the Treaties, for example, regarding family matters. Nor is the EU Court of Justice immune to criticism. Its case law is riddled with rulings which blithely interpret European law to tip the balance in the direction of the Union’s competencies, without an explicit conferral or in blunt contempt of the Treaty.

Yet the best example of this trend towards an ever-growing extension of powers remains the notorious Article 7 TEU on the protection of ‘common values’. This provision has the widest possible scope, as it applies to every field of national competence where those values might be at stake. Just that. It is a real hold-up of powers for the benefit of the Union, in total disregard of the principle of conferral of powers. This is not the least of the paradoxes for a provision allegedly protecting the rule of law. Not to mention the prominent role the Commission assumed in this area, without a clear mandate from the Treaty.

‘Paradoxically, the more Europe has expanded, the more its ideological diversity has shrunk’

These behaviours constitute a drift towards bad practice, at odds both with the letter and the spirit of the Treaty. A Union which proclaims itself a champion of the rule of law must apply those principles in a rigorous and coherent manner, and enable a culture of subsidiarity and attribution which makes sense of those core, yet neglected principles.

Denial of Diversity

Neglecting the principles framing its competences while proclaiming that the protection and promotion of those ‘common values’ is the main raison d’être of the Union is symptomatic of a providential and detached mentality. This is problematic for at least two reasons.

In the first place, we must once again insist on the generic and vague character of those values. According to Article 2 TEU, ‘The Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law, as well as respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities. These values are common to member states in a society characterized by pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men.’ These might be originally Western concepts that are now found in many constitutions of third countries and somehow became ‘universal’, but they are not specifically European in the same way that being European means much more than adhering to those values. But above all, they leave significant room for interpretation, and would otherwise be empty shells. Thus, these concepts have a common base, but above all, they lead to very different interpretations depending on the countries where they apply and depending on, well, the people who apply them.

Secondly, generic values are ideologically permeable, and can easily become pretexts for the imposition of a determined political vision, especially when they are compulsively invoked by political leaders in their speeches, and not just by judges in their courtrooms. If, moreover, ‘decision-makers’ suffer from a lack of political legitimacy because their accountability to voters is much more diluted than at the local or national level, then we run the risk of ‘top down’ governance. That might look democratic, but it is not.

Is this the case in the EU? It is an open question, but some reflexes and practices leave room for concern. Certain choices, political initiatives, the way certain funds are managed and allocated, the tone of the communication, the discretion to launch infringements, the influence of certain lobbies, and the blessing of civil society (too often confused with the citizens themselves) invite scepticism.

This quasi-religious fervour goes together with a lack of political diversity (to use a fashionable term). Paradoxically, the more Europe has expanded, the more its ideological diversity has shrunk, to the point that any debate on Europe is drowned in simplistic and binary visions. Challenging the Union’s course is tantamount to opposing the very idea of cooperation between European countries through common institutions. The EU increasingly becomes a ‘take it as it is or leave it’ question. Either federalist, liberal and multicultural, or on the wrong side of history. And this is one step too close to considering dissenting opinion as being contrary to those ‘common values’, the main benchmarks of good and evil. Hence the well-founded fear of seeing these fundamental principles become an ideological instrument to narrow the circle of legitimate opinions and drown the debate. The more some elites praise diversity and inclusion, the less they implement it at the political and intellectual level. Is Europe weaker if it is nurtured with different perspectives?

Conclusion

After ten years of endless crises, wisdom dictates that the Union heal its wounds, strengthen its internal cohesion and convince citizens of its added value. Unfortunately, neither the pandemic nor the resounding return of geopolitics will give it this respite. And in the face of these challenges, which require ambition and daring, the temptation is great for the EU to think of itself as the one and only remedy. Admittedly the Recovery Plan is a response that matches the magnitude of the crisis and will probably be decisive, but it also implies an extraordinary cession of powers to the Union and a federalization which does not dare speak its name. Both the circumstances of this breakthrough (which is the result of urgency, not a thoughtful political choice) and the geopolitical challenges that await the Union at the turn should invite the latter to be much more pragmatic.

In order to exert influence on the international scene and assert its sovereignty, the EU should first consolidate its internal cohesion and create a basis of mutual trust with and between member states. This is the most reasonable ‘reset’. Unfortunately, developments in the EU since the Maastricht Treaty and more recently do not bode well. Far from being pragmatic, the EU persists in taking the path of dogmatism and messianism. It denies its origins, neglects some of its fundamental principles, and focuses on ‘common values’ which undermine its political and cultural diversity and stifle internal debate. Thus, it jeopardizes its own future by moving away from its two main sources of legitimacy (states and citizens) and by dreaming of itself as sovereign without even considering that its sovereignty depends on that of the member states.

Perhaps the elites of Brussels are haunted by the idea of being an economic giant and a political dwarf. But all in all, who is more vulnerable than a dwarf who sees himself as a giant? Like the frog in Aesop’s fable, the EU, swollen with pride, in defiance of the facts, risks bursting by trying to ape what it will never be: the United States of Europe.