Over this weekend, Brazil is facing what many call a mega election: a third of the 81-member Senate, all 513 deputies and all 27 governors will have to be elected for another term. However, none of these will have such an impact on the future of the country as the presidential race. Topping the polls we find head-to-head the two political giants of contemporary Brazil: the sitting president since 2019, conservative Jair Bolsonaro, and the former president and social-democrat Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva who lead the country between 2003 and 2010, with the highest presidential approval rates in Brazilian history.

While Bolsonaro’s national conservative Social Liberal Party (PSL) played only minor, if any, part in Brazilian politics before the 2018 elections, Lula’s Workers’ Party (PT) is historically the biggest and strongest political force in Brazil and held the government for thirteen years out of the last twenty. Nonetheless, despite being a relative newcomer to the country’s high politics, Bolsonaro’s term showcased his ability to act as a strong and charismatic leader that shakes up the nation like a storm, therefore he shouldn’t be written off just yet, because his 2018 surprise victory might just as well be repeated.

Despite the fact that the campaign was dominated by fearmongering on both sides (depending on whom you ask, either communist Lula or fascist Bolsonaro will surely bring about the collapse of Brazil), voters don’t seem to be swayed too much by the ideological name-calling. The real question for the people is whether they want to revert back to the comfortable socialist welfare policies of the PT accompanied by Lula’s pragmatic foreign aspirations, or do they want to carry on with Bolsonaro’s business-oriented, ‘Brazil First’ approach?

One Country, Two Visions

First and foremost, Bolsonaro has always been the president of the middle class. His 2018 campaign was focused on social conservatism, Christian values and family-oriented policy-making, with a promise of law and order (upheld by a strengthened military and police force), booming businesses, as well as the protection of landowners and gun ownership laws. His term was marked by across-the-board tax and tariffs cuts, the weakening of federal agencies (according to the principle of subsidiarity), and by frequent confrontations with the green lobby over the retainment of traditional energy sources and the low prices associated with them.

Despite heavily leaning to the left, Lula was able to create an especially stable political system that incorporated everyone

In contrast, Lula is all for Brazil’s vast working and lower classes. The veteran politician now rolls into the finish of his sixth presidential campaign with the promise of restoring the country to what it was under his long leadership, mainly characterised by enormous social programmes paid for through increased taxes and tariffs on Brazil’s booming commodity market. He was known for his famous ‘Zero Hunger’ programme: a scheme that used various policy tools to lift thousands out of extreme poverty. As a former union leader, Lula also paid special attention to the workers’ needs when establishing a more stable macroeconomic standing for his country. Despite heavily leaning to the left, Lula was able to create an especially stable political system that incorporated everyone, and was marked by a gradual convergence of interests between the private industry sector and the organised labour force—and between the lower middle class and the poor—which gave birth to a new political ideology called Lulism. It’s no surprise, therefore, that when Lula left office his approval rate stood at an astonishing 83 per cent.

Against a politician with such a shiny legacy, right-wing Bolsonaro’s fight for reelection seemed futile from the start. Some suspect that his 2018 victory was only made possible by the fact that Lula was unable to enter the race because he was spending jail time at that time for corruption—a sentence that was reversed by the supreme court two years later, restoring his political rights and his honour in the eyes of most Brazilians. Now he’s able to face Bolsonaro for the first time, and their battle will be one between two fundamentally opposing visions of Brazil.

What Do the Polls Say?

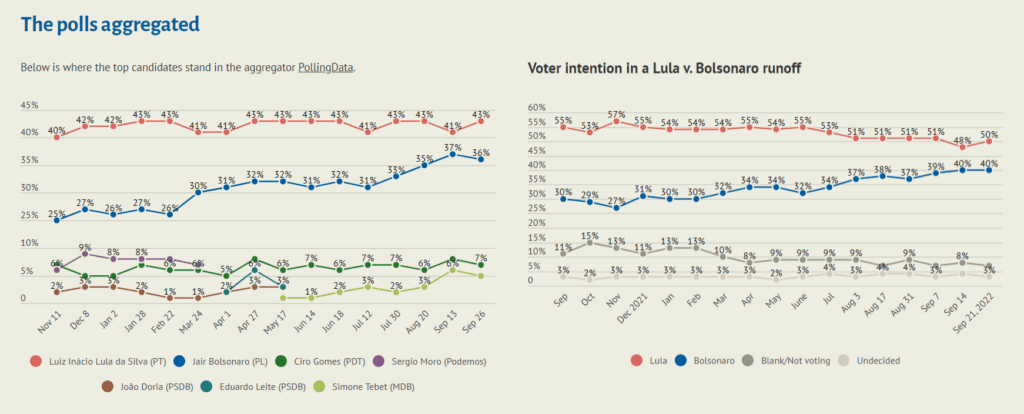

Since he’s become the living symbol of political stability, Lula’s polling numbers were consistently high throughout the past year, averaging between 40 and 43 per cent. By contrast, Bolsonaro’s support was measured at only 25 per cent a year ago, but he slowly climbed up to 36 per cent as of 26 September. There are two more candidates who haven’t dropped out of the race, but they aren’t likely to get more than a couple of per cents in the end. Nevertheless, their voters might end up deciding the final outcome, as Brazil has a two-round electoral system: if neither candidate reaches fifty per cent of the votes, the two top candidates will have to face each other in a runoff a month later. Therefore, whoever can rally the voters of the lesser candidates will likely come out victorious. Unfortunately for Bolsonaro, when respondents were asked about their preferences in the case of a hypothetical runoff, Lula still came out on top, with fifty per cent, in contrast to the incumbent president’s forty.

Two more sets of data can be quite revealing when it comes to voting patterns. One is that according to the respondents of a survey, the two principal problems of Brazil are the economy and poverty. Other issues such as corruption, violence, or education come much lower on the list. Unsurprisingly, those concerned about their economic wellbeing tend to vote for Lula, while Bolsonaro’s supporters value security and anti-corruption more. In addition, those who marked healthcare and pandemic response as their top concern also tend to favour Bolsonaro, which is quite interesting, since the president came to be known as one of the world’s greatest opponents of vaccine mandates, lockdowns and other Covid-related measures. While more than seventy per cent of the country is vaccinated against the coronavirus, it seems that people do appreciate having a choice on the issue.

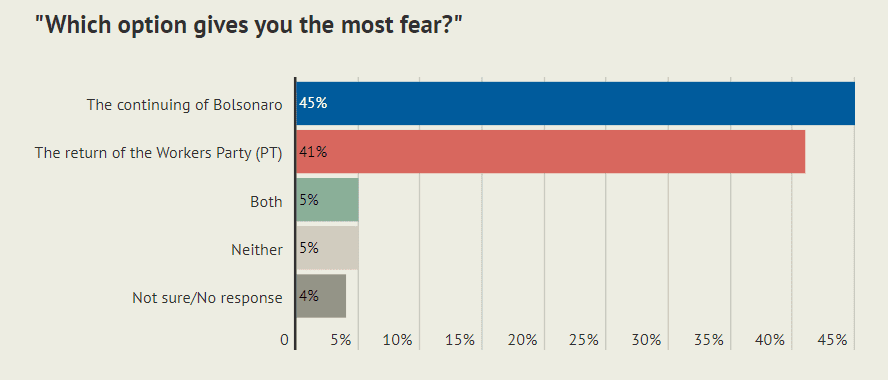

Another remarkable poll that is worth mentioning reveals that due to the especially heated election campaign this year, more people seem to be planning to vote against a party or a person than vote for them. When respondents were asked what they fear the most, even though the answer ‘Neither’ was also included the vast majority did have a clear choice. In this setting, too, Lula comes out better.

What Can the West Expect?

Now, despite Lula and Bolsonaro being total opposites when it comes to how they intend to run their country, from a foreign policy perspective their differences are much more subtle. The primary question of course is Brazil’s future involvement within BRICS, the intergovernmental cooperation platform that includes Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine began (and even before that), many in the West have feared that Moscow and Beijing would want BRICS to become some kind of global anti-Western alliance. These concerns grow by the day after two new countries—Iran and Argentina—have applied for membership recently, and three others are currently considering it. Therefore, if BRICS was rendered an instrument of war—whether actual or just economic—the Brazilian president’s person and his relation to the West could gain sudden importance. Without going into great detail, which wouldn’t fit the scope of this article, it is fair to say that Brazil wouldn’t pose much risk to the West under the leadership of either candidate.

On the one hand, as one of its original founders, Lula is much more committed to BRICS than Bolsonaro would ever be. He was the one who transformed Brazil into the giant commodity exporter it is today, primarily by joining and expanding regional or global networks and diplomatic partnerships, such as BRICS, Mercosur and the Union of South American Nations. These policies lead to Brazil’s GDP increasing more than fivefold between 2003 and 2011. We can therefore expect that President Lula, if elected, will continue his legacy and become increasingly involved with BRICS once more.

Many experts predicting an eventual ‘Braxit’

By contrast, Bolsonaro is known to attribute much less value to the bloc, and his constant criticism has left many experts predicting an eventual ‘Braxit’. This was mainly because of Bolsonaro’s fiercely anti-Chinese rhetoric which was strikingly similar to that of Donald Trump: both accused China of using their economic power in the West to sow malign political influence. Therefore, in countering growing Chinese influence, Bolsonaro became on of the US’s most trusted allies, and the recommitment of the US-Brazil Security Forum in 2019 was the most obvious sign of Brasilia’s newfound alignment with Washington and NATO, as well as of its distancing itself officially from China.

Based on this, the answer seems simple: from a strategic point of view, the West wins with Bolsonaro and loses with Lula. However, as some experts argue, the outcome depends on who sits in the White House just as much as who the President of Brazil is.

Bolsonaro found an important ally in Trump, but not so much in Biden as of late. Since the Democratic Party essentially spent the last four years demonising him, he could—in theory—turn towards other countries, like Putin’s Russia or Xi’s China, in the absence of Western allies. The same principle applies to a Lula presidency as well: Democrats will expectedly embrace him for sharing the same leftist platform as they do and provide new opportunities for US-Brazilian cooperation. But the pragmatic and moderate foreign policy maker he is, Lula will never make an exclusive choice between Beijing and Washington, but will likely seek balance in working together with both as far as Brazil’s interests align, and avoid being caught up in the two countries’ strategic rivalry.

Therefore, the question of whom should the West root for in this election stands rather unanswered. Both candidates have strategic advantages and disadvantages, while Brazil’s involvement in the coming storm very much depends on the West itself, especially on the sitting US administration. But either way, this influence will likely be marginal. Latin America will play a much greater role in the century’s economic history, but less so in the current geopolitical conflict.

Of course, conservative governments—and conservative people—around the world are likely to support Bolsonaro over Lula, simply based on the ideological similarities and shared values. Such values made it easier for any like-minded government to develop their partnerships with Brazil over the past four years, the same way left-wing governments will find an easier route to Lula’s heart if he stands victorious. If the polls are correct and Bolsonaro doesn’t produce an unexpected, last-minute miracle, I’m afraid left-wing governments have reason to rejoice from January 2023. Conservatives worldwide, and especially in the West, are standing to lose a valuable ally in Bolsonaro, that is certain. Nonetheless, the will of the people must always prevail.