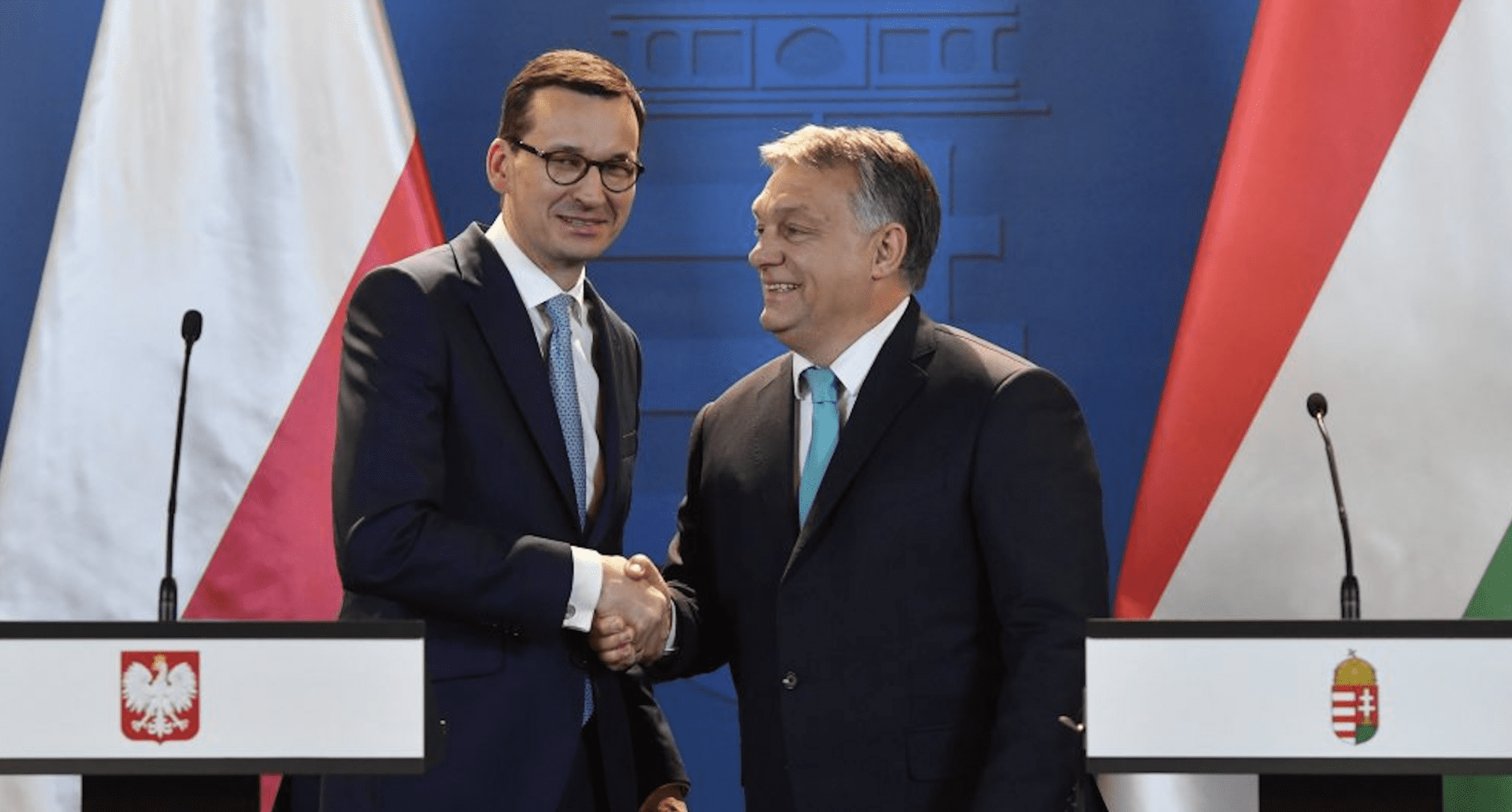

After a temporary split caused by differences on the war in Ukraine, Poland is about to warm its ties with Hungary again, a move that could also bring about the revival of the V4 cooperation.

‘The approach to the war has really divided us. But I think that in time, all the other issues where we have shown solidarity, understanding and support will bring us together again. I would very much like that. We all know that cooperation within the Visegrad Group strengthens our countries considerably. In this case, 1 plus 1 plus 1 plus 1 is not four, but seven or eight. That is why our group will survive despite the differences—sometimes big differences—between the governments of the particular countries,’ Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki told Polish pro-government magazine Sieci last week. ‘With respect for the sensitivities of our Ukrainian friends we can return to both V4 cooperation and joint action with Hungary in areas where we share common values and interests,’ he stated.

The Polish prime minister’s statement has received special attention in the Hungarian press and has also been covered by the international media for quite a few reasons. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, relations between the Visegrad countries and between Hungary and Poland, in particular, have deteriorated, due to different attitudes to the war. Although the ‘Visegrads’—comprised of Slovakia, Czechia, Poland, and Hungary—have achieved many successes in recent years by being able to formulate joint positions and amplifying their voice in Brussels on such matters as migration or the EU budget, the war in Ukraine seemed to bring the cooperation to the end.

A Serious Setback

One can argue that the reason for the cooling of relations between the V4 countries is that Slovakia and Czechia decided to place their bet on deeper integration with the European Union, rather than on regional cooperation. But this is probably only a minor reason. The main reason for the unravelling of the V4 cooperation was driven to greater extent by the growing tensions between Budapest and Warsaw—the two V4 members who have been the main promoters of the alliance since its inception.

Although different views on Russia have always been present among V4 countries, the first major disagreement between Hungary and Poland arose over arms shipments to Ukraine. Poland, as the EU-wide leading advocate of arms shipments to Ukraine, has transferred more than $7 billion worth of military equipment to its war-battered neighbour so far, including 200 T-72 battle tanks, MIG-29, and Su-27 fighter jets. By contrast, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has been tenacious about Hungary not selling weapons to Ukraine and not allowing arms shipments transit its territory, to avoid the spillover of the conflict, and for the sake of the security of the around 156,000 ethnic Hungarians living in Transcarpathia.

Dividing lines also seem to run deep when it comes to Russian energy. However, in this regard Hungary does not stand alone. Hungary, Czechia, and Slovakia, all landlocked countries and linked to the massive Russian-operated conduit Druzhba, have all resisted approval of the EU’s sixth sanction package which aims to phase out all Russian crude in six months and all refined oil products by the end of the year. These countries not just heavily rely on Russian oil imports (Slovakia gets 78 per cent, Hungary 45 per cent, Czechia 29 per cent of its oil from Russia) but their refinery infrastructure also works exclusively with the Russian Urals Blend, so switching to a Western blend also requires time and hundreds of millions in investment. Although Poland is also highly reliant on Russian crude imports (68 per cent), those constitute only 24 per cent of the country’s energy mix ; furthermore, it is the only V4 country that has access to the Baltic Sea and has an LNG terminal on its shore. That is why Poland could propose its radical plan to become independent of Russian oil and gas as soon as by the end of the year (!) while Hungary, Czechia, and Slovakia had to get into a fierce debate within the EU to secure temporary exemption from the bloc’s Russian oil ban.

There have been spectacular indicators of the deteriorating relations between the Visegrad countries, such as the cancelled meeting of the V4 defence ministers in March or the repeated open criticism of the Hungarian approach to the war from polish Law and Justice governing party leader Jarosław Kaczyński, who is otherwise considered one of Viktor Orbán’s main European allies. Although the V4 chiefs of staff meeting did take place in June in Hungary to discuss the future of military cooperation, Poland stayed away.

At the end of July, Orbán also admitted that Polish-Hungarian relations, which could be considered the axis of the V4, have been shaken by the war and talked about the era of close cooperation within the V4 in the past tense. Days later Morawiecki confirmed the Hungarian PM’s words, confirming that Poland and Hungary have indeed ‘parted ways’.

What Caused the Turnabout?

In the meantime, Warsaw was in continuous discussion with the European Commission on the country’s recovery and resilience plan, to finally be able to receive €23.9 billion in grants and €11.5 billion in loans under the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). At the beginning of June, the European Commission gave a positive assessment of Poland’s plans, however, called for several judicial reforms including the scrapping of the contested disciplinary chamber for judges.

Up until the end of the summer, it seemed that Warsaw was willing to enact some reforms and was ready to reach an agreement with the Commission, which was otherwise pleased to see the Poles become advocates of European unity in helping the Ukrainian war effort. The Commission giving green light to the disbursement of the RRF funding would have meant Hungary losing Poland in the Brussels ‘battlefield’ as a major ally in the fight for recovery funds, and remaining the only country that has still not received a cent from RRF. During the summer, it seemed that Brussels was also aware of this situation, and would employ clever tactics to achieve reforms in Poland and isolate Hungary at the same time.

But by the end of August, it became clear that despite the EU Commission’s and then the Council’s endorsement of the Polish recovery plan, and Poland’s rule of law reforms, Warsaw will not see RRF money any time soon. The Commission said Warsaw’s reforms were insufficient, and it started imposing more and more conditions that Poland was supposed to fulfil in order to receive the money.

Brussels’ unexpected change of heart caused outrage among leading Polish politicians. President Andrzej Duda voiced his disappointment stating that the European Commission had broken the agreement on the Polish recovery plan. He stressed that the EU cearly sees the issue as a political matter.

Justice Minister Zbigniew Ziobro, leader of the Eurosceptic Solidarity party, used a stronger tone and accused European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen of deceiving the Polish government.

‘If Brussels continues to withhold funding, so be it. We can manage without it,’ argued Mateusz Morawiecki, and added that his government would not propose further reforms to alleviate the EU’s concerns about the rule of law in Poland.

Brothers in Arms

Brussels’s deception has not only triggered outrage in Warsaw, but has also prompted a strategic change. Or rather, a return to the old strategy—meaning that Warsaw is to side once again with Budapest against Brussels, while seeking to revitalise the regional V4 cooperation. ‘The Polish and Hungarian positions are very much in line, so I want to cooperate as closely as possible within the Visegrad Group on all issues affecting our region,’ the prime minister highlighted in an interview with Polish paper Salon24.

And both Hungary and Poland could use one other’s helping hand, considering the uphill fights they still face in the EU. On the one hand, their efforts to finally attract RRF funding or rule of law debates seem a protracted struggle. On the other hand, energy and climate policy seem to be emerging as a new point of disagreement between Warsaw and Brussels as Poland seeks to emerge as a regional energy power. And with the completion of the Baltic Pipe gas pipeline, its LNG terminal already operational in Swinemünde and the development of an oil refinery in Gdansk to supply East Germany and Berlin with gas, it may very well become one. Thus, Poland may raise several obstacles to Brussels’ progressive green policy and climate goals, and together with Hungary, could further hamper the EU institutions’ actions aiming to erode the sovereignty of the Member States.