For Romania, the home of a more than one-million strong ethnic Hungarian community, 2024 will be a year like no other. There will be European Parliament, presidential, parliamentary, and local elections. On three different dates! And the stakes are high.

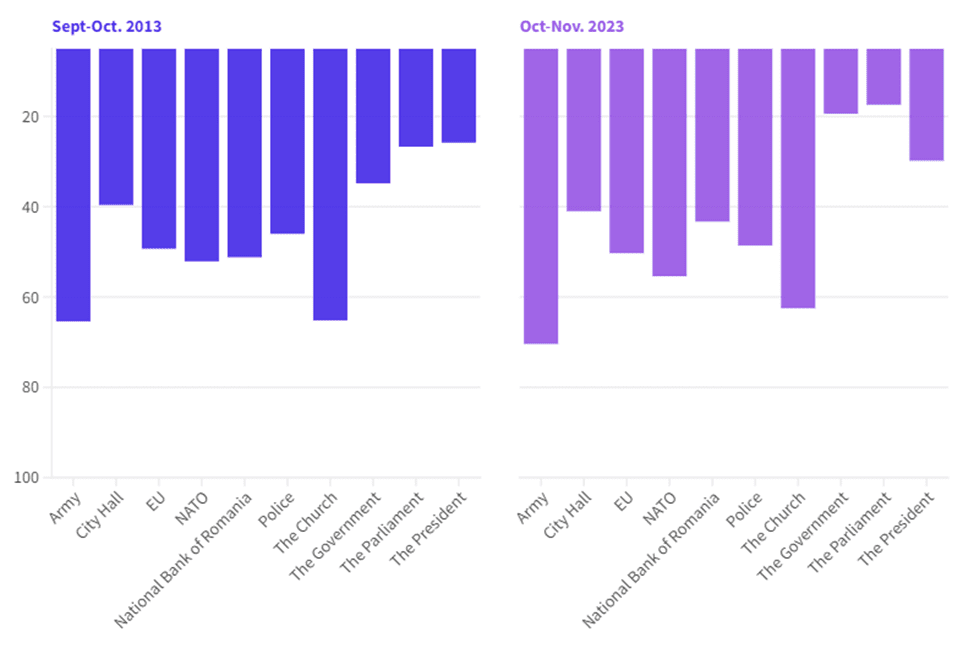

The three most common things that come to their mind when I talk to people about my home country are Andrew Tate, cheap vacations, and Dracula. If they are Hungarian, they will also mention the Hungarian ethnic minority living beyond the border. But the country is about much more. It has seen a lot of transformation since the fall of Ceausescu’s totalitarian regime in 1989; it has become increasingly important both in economic and geostrategic terms. However, its complicated political bureaucracy, and the society’s growing distrust in the political system have made it hard for it to fully capitalize on its diplomatic leverage.

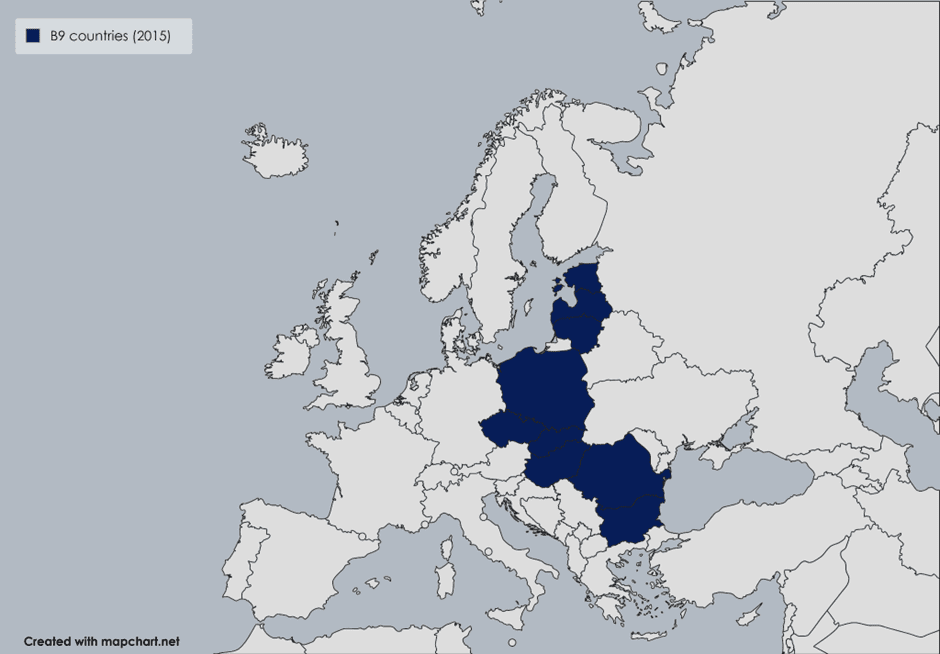

After the Russian annexation of Crimea, Romania and Poland―the two biggest NATO countries that joined the alliance after 1999―found themselves in a peculiar position. Both feared a potential aggression from the east, and both felt weak to protect themself. Thus in 2015 Romanian President Klaus Iohannis, his Polish counterpart Andrzej Duda and other Eastern-European countries initiated two collaboration forums: Bucharest9―which was formed with NATO member states―and the Three Seas Initiative, in order to strengthen the region’s military and economic potential. In July 2017, US President Donald Trump attended the 3SI Warsaw Summit and called the event ‘incredibly successful.’

The coastal region of Dobrogea makes the country an invaluable asset for NATO and the US, but at the same time is the Achilles heel of Romania. The Danube Delta and the surrounding region witnessed significant military engagements during this Russo–Turkish conflict between 1806–1812, with both empires vying for control and dominance in the region. Through the delta you can unnoticeably access the heart of the country, and this vulnerability makes policymakers in Bucharest concerned.

At the beginning of this year, near the coastal city of Constanța NATO began to expand the Mihail Kogalniceanu military base, which will be able to host around 10,000 troops by the end of the decade, surpassing in that regard Ramstein in Germany.

In addition, over the past years huge offshore gas reserves were discovered near the Romanian coast, in the order of magnitude of some 200 billion cubic metres of natural gas. In 2023, 1 billion cubic metres were already extracted.

But let’s turn from geopolitics to domestic issues. It is worth pointing out that Romania’s political framework is a semi-presidential representative democratic republic where the Prime Minister is the head of government while the President, according to the constitution, has a more symbolic role. The head of state is responsible for the foreign policy, signs certain decrees, approves laws promulgated by the parliament, and nominates the head of government.

The complicated political system, and the fact that the people are called three separate times to the polls this year may lead to the success of the more radical messages, because they are simple and smartly formulated. However, according to a survey conducted in April, more than half of those surveyed stated that in the European Parliament elections, they would vote for the party to which their preferred candidate for mayor belongs. This reflects the tendency of trusting local policy makers rather than politicians at the national level who constantly argue with each other in the capital city.

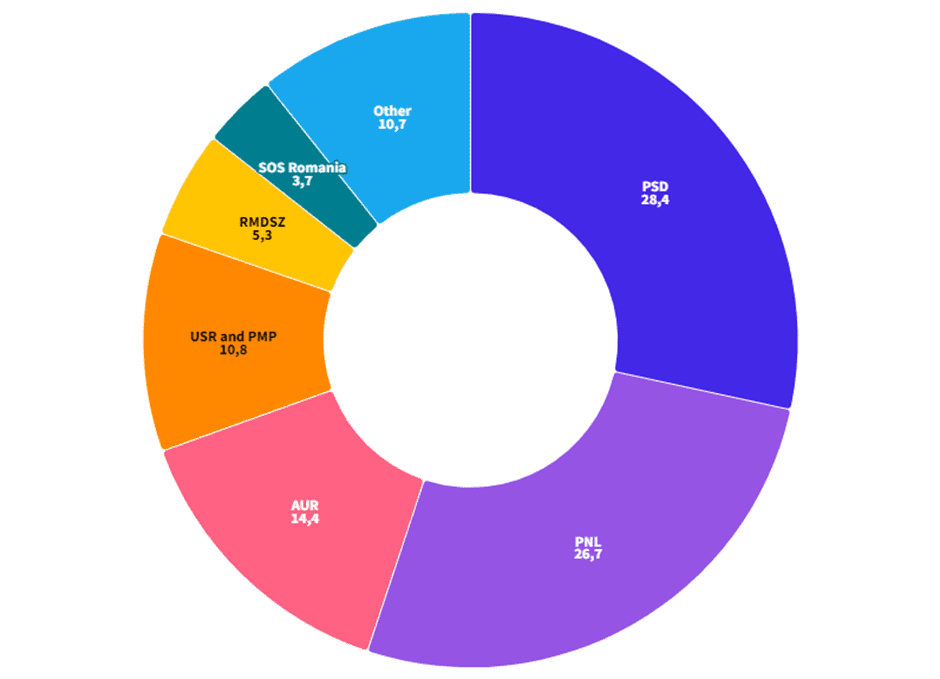

Just like in many other countries in the Western hemisphere, there are old, mainstream parties, who make agreements and decisions together on one day, and become archenemies on the other. In Romania, they are the social-democrats (PSD), social-conservatives (PNL), a moderate conservative party called People’s Movement Party (PMP) and the Hungarian RMDSZ. On the other hand, there is a youngish, Eurocentric party, called USR (Save Romania Union) and two radical nationalist parties called AUR―which in Romanian means gold― and S.O.S. Romania.

These latter two became crucial parts of national politics during the 2020 parliamentary and local elections, building their identities around their seemingly charismatic leaders―George Simion at AUR and Diana Sosoaca at S.O.S.―and the strong anti-vaccine sentiment in the country. In fact, until the end of September 2021, only 33 per cent of the population was vaccinated. And both parties definitely lack what Eric Hendricks called ‘serious conservative ideas, prestigious knowledge, institutions, and solid talent pool from which to draw policymakers’ in a recent article on Hungarian Conservative.

Ideologically the two parties are rather close, however, their leaders have serious personal issues with one another: they both have the ambition of becoming the main figure of the newly emerged radical movement. Thus, it is unlikely they will be able to work together on any issue.

It would also be far-fetched to presume that they will be able to win the presidential seat, but AUR, being the third most popular party in Romania―with around 15,000 members―, will certainly be able to make its voice heard. Their slogan is ‘Faith, Nation. Family and Liberty’, and this is what they claim on their official website: ‘The idea of national unity must be illuminated by Christian morality, which means love for your neighbour, for your family, for your nation, for the nations around you, for humanity.’ Sounds nice, right? But the reality about the party is much grimmer.

Contrary to the lofty rhetoric on the website, George Simion, after he got banned from Moldova, claimed that it is not a country, only a state. He has also suggested that members of RMDSZ want to steal Romania, and many of them are actual terrorists; but it was much earlier that Simion became (in)famous.

In the early summer of 2019, together with Romanian football hooligans, he vandalized a Hungarian military cemetery and attacked the ethnic Hungarian citizens and politicians who were trying to protect their heritage.

In another incident, George Simion ambushed Botond Csoma, leader of the RMDSZ parliamentary group, in the corridor of the Romanian Parliament, filming him with his phone, and berating him in unacceptable language, because the Hungarian members of the national hockey team had sung the Székely anthem before a match.

In fact, ever since Simion and his party won parliamentary mandates their main political weapon has been to verbally harass their opponents on the streets and in public institutions. These undignified encounters can be watched on the party leader’s TikTok account. Their other strategy is to communicate acceptable messages on official platforms but use insulting and extremist language in the comment section or Facebook groups. Thus, these remarks can be called fake or not serious. This two-facedness helps them build a good reputation among other conservatives in European politics, and in the meantime gain political support among far-right voters with the most retrograde rhetoric. The biggest issue with this attitude is that as a result political discourse sinks to such lows that the democratic institutions become a source of mockery in the eyes of the sane public, making a potentially promising country an embarrassing and problematic ally.

Related articles: