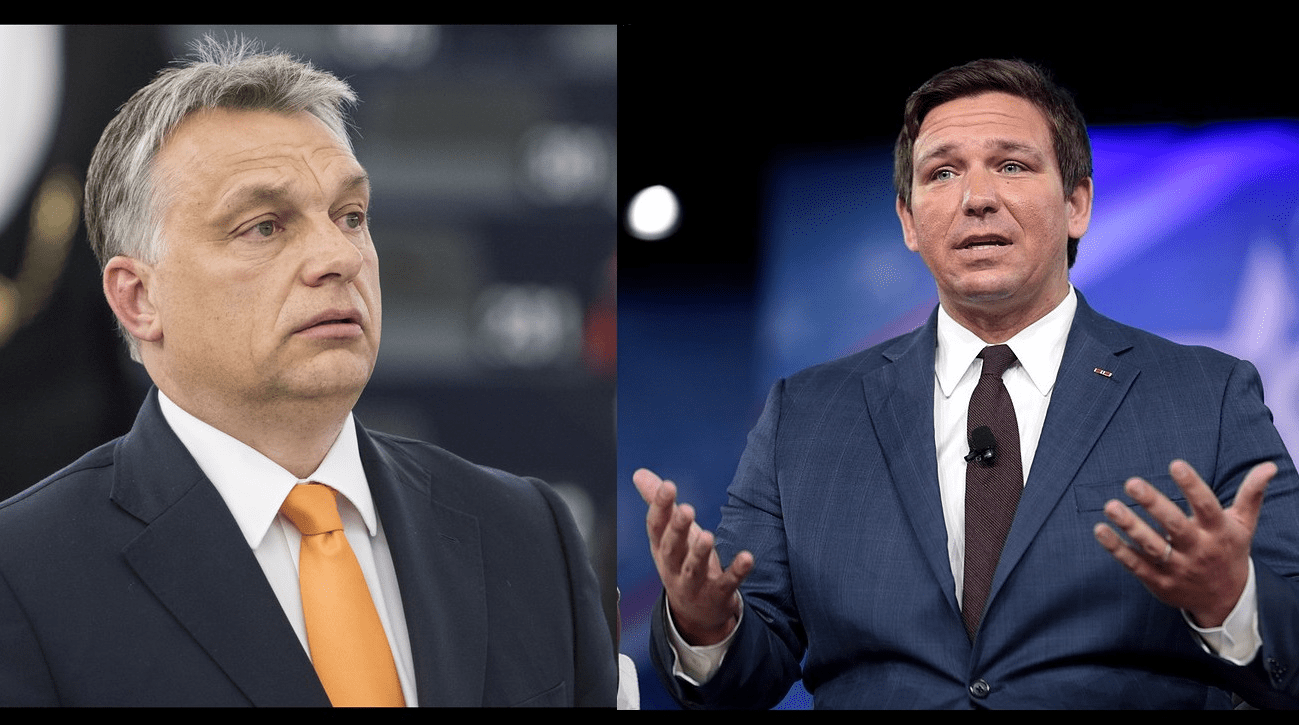

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis won re-election in a landslide back in November 2022—quite an improvement in performance after his razor-thin win in 2018. The Republican statesman beat his Democratic opponent Charlie Crist by 19.4 percentage points, outperforming even the polls that had put him in a firm lead. Earlier that year, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán had a thumping victory of his own, securing his fourth consecutive term in office. He beat the candidate put forward by the united opposition, Péter Márki-Zay, by almost exactly the same margin as DeSantis in the popular vote contest.

However, this is not where the similarities between Governor DeSantis and Prime Minister Orbán end.

Earlier this week, we published an interview with Christopher Rufo, a Senior Fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a Visiting Fellow at the Danube Institute, in which we asked if he believes Governor DeSantis has taken inspiration from the policies of PM Orbán. He claimed he is not aware of any direct inspiration, but he does see the similarities. Would that mean that those similarities are purely coincidental? Let’s examine that.

Orbán and DeSantis’ Stances on the Teaching of Gender Theory in Schools

The Hungarian parliament passed the Child Protection Law in June 2021, restricting the teaching of gender theory and the promotion of gender change procedures to minors in schools. It bans any persons who are not employed as a teacher, perform health care duties in the schools, or are affiliated with any state organisation working in cooperation with those schools, to provide sexual education to children in any public institution. Also, it compels electronic commercial service providers to follow the guidelines of a 21-member round table on putting out age-appropriate content.

The passage of this piece of legislation caused great international costernation—its news certainly reached the south-eastern shores of the United States as well.

Fast forward to March 2022, and Governor Ron DeSantis signs into law in Florida the Parental Rights in Education Act. It also bans third-party actors from providing sexual education to kids from kindergarten to Grade 3 in public schools; while it also requires the schools to keep the parents informed about what is in the curriculum if such information is solicited.

The left-wing media in Hungary, Western Europe, and the United States alike applied the same tactic when trying to drum up negative sentiment in the public toward the respective bills: that is, consistently labelling them as hateful and discriminatory. In the case of the Hungarian law, it was simply dubbed ‘anti-LGBT’ or ‘homophobic’. Meanwhile, in the case of Florida, journalists came up with the catchier, rhyming label ‘Don’t Say Gay’.

In both instances, the defence of the bills’ authors was, to oversimplify it, ‘read the text’, as no phrase referring to the LGBT people appears in either one.

Below, you can see Governor DeSantis eloquently making that point at a press conference in March 2022.

Ron DeSantis ‘schooled’ journalist over education bill

Sky News host Rita Panahi says Florida governor Ron DeSantis gave a lesson in how to handle “dishonest media pushing a narrative” at a press conference discussing the state’s new education bill. “Future US president and current Florida governor Ron DeSantis has schooled an activist journo about a new bill that the media is dishonestly calling the ‘don’t say gay’ bill,” Ms Panahi said.

Renowned author and columnist Rod Dreher, a Hungarian Conservative contributor and Danube Institute visiting fellow, was not shy about pointing out the connection between the two pieces of legislation back in April 2022. He had this to say at a panel discussion at the Danube Institute at the time:

‘About the “Don’t Say Gay law”, it was in fact modelled in part on what Hungary did last summer. I was told this by a conservative reporter who…said he talked to the press secretary of Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida and she said, “Oh yeah, we were watching the Hungarians, so yay Hungary”.’

Orbán and DeSantis’ Stances on Immigration and the Ukraine War

In September 2022, Governor Ron DeSantis pulled quite an ingenious stunt by sending 50 illegal immigrants, primarily from Venezuela, who were held in Florida after apprehension, to the extremely affluent neighbourhood of Martha’s Vineyard in Dukes County, Massachusetts. With this bold move, he successfully highlighted the hypocrisy of many from the wealthy elites pushing for lax immigration enforcement on the Southern border, while not having to live with its immediate consequences. Within a week, the 50 migrants were relocated, with the assistance of Republican Governor Charlie Baker.

Viktor Orbán is yet to put on a public spectacle like that regarding immigration, but he has used vivid imagery of the masses of migrants and the fence on Hungary’s southern border to convey his stance against illegal immigration very effectively as well.

On the topic of the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war, DeSantis has called for less involvement on the US’s part and criticised the Biden administration’s ‘blank check’ policy. However, he has also engaged in some aggressive rhetoric at other times, calling Russian President Vladimir Putin a ‘war criminal’. Orbán has expressed negative sentiments concerning the extent of American military involvement in the conflict as well, and has been consistently calling for a negotiated peace.