This article was published in Vol. 3 No. 2 of the print edition.

New Russian Doctrine

The current conflict and growing ideological gap between Russia and the West require a comprehensive analysis of the re-ideologization of Russian domestic, foreign, and security policy. This re-ideologization was already visible at the beginning of Vladimir Putin’s third term as president of the Russian Federation in 2012. Putin’s so-called ‘conservative turn’ is in full accord with the political doctrine developed in numerous Russian intellectual circles and think tanks, identifying themselves as neoconservative. This doctrine maintains that a state without ideology cannot be considered sovereign. The intellectuals of the conservative camp have long since maintained that the ban on state ideology in Russia (Chapter 1, Article 13 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation) is extremely harmful for Russia’s national interests and security. After the collapse of the Soviet Union and the rejection of Marxism there was no ideological alternative to the liberal model of domestic, foreign, and security policy, until now.

What is this Russian doctrine, proposed by some conservative intellectuals as the foundation of the new Russian state ideology? It relies on the Katechon narrative, according to which Russia is a ‘shield’ protecting the world from the apocalyptic forces of chaos, and the concept of ‘Atomic Orthodoxy’, which ties together Christian messianism with nuclear defence policy. This new conservative narrative is characterized by a strong anti-Western (anti-American) sentiment, without denying Russia’s European identity. The third element of the doctrine is the narrative of Russia as Europe without the West.

The concept of Russia as Katechon was widely discussed in influential conservative intellectual circles during the last two decades. It was offered to the Kremlin (without using the term ‘Katechon’) as the basis for Russia’s new state ideology ten years ago, during the protests by Russia’s non-systemic liberal opposition in 2011–2012 and Putin’s presidential campaign. The godfathers of post-Soviet conservatism are the writer Aleksandr Prokhanov, the political analyst Sergei Kurginyan, and the philosopher Aleksandr Dugin. Their projects for the future Russia—The Fifth Empire, The Soviet Union 2.0, and The Eurasian Empire—differ in detail, but all proclaim state messianism and imperial utopianism, and employ anti-Western rhetoric. I believe that the main political processes after 2012, such as the new law initiatives, for example the foreign agent law, the concepts of ‘Russian traditional values’, the ‘Russian approach to human rights’, the annexation of Crimea, and the war in Ukraine—have to be interpreted in the light of the ‘Katechonic’ ideology.

‘The ideologization of domestic, foreign, and security policy can be seen as Putin’s attempt to legitimize his own power’

I see the contemporary actualization of the Katechon-ideologeme as one of the main factors accounting for the popularity among ordinary Russians of Putin’s war against the West. New Russian messianism is seen by its proponents as an alternative to the doctrine of American exceptionalism, and as an important ideological tool for openly challenging Western hegemony and creating a new polycentric world order. When Dmitry Medvedev says in a message marking Russia’s Day of National Unity (4 November 2022) that Russia’s task is to ‘stop the supreme ruler of Hell, whatever name he uses—Satan, Lucifer or Iblis’1—he is referring to the Katechon-narrative. It is true that the ideologization of domestic, foreign, and security policy can be seen as Putin’s attempt to legitimize his own power, and his support by the population can be put down to state propaganda, but in my opinion such explanations ignore the important factor of collective memory and identity and the deep roots of Katechonic discourse in Russian culture, both pre-revolutionary and Soviet.

Russia the Restrainer as a National Idea: Katechon and Anomia

The word ‘Katechon’ is from the Greek ό Κατέχων, meaning ‘the withholding’. The Christian eschatological interpretations of Katechon are based on the Second Letter of St Paul to the Thessalonians:

‘Let no one in any way deceive you, for it will not come unless the apostasy comes first, and the man of lawlessness is revealed, the son of destruction, who opposes and exalts himself above every so-called god or object of worship, so that he takes his seat in the temple of God, displaying himself as being God. Do you not remember that while I was still with you, I was telling you these things? And you know what restrains him now, so that in his time he will be revealed. Fort he mystery of lawlessness is already at work; only he who now restrains will do so until he is taken out of the way.’ (2 Thess. 2:3–7)2

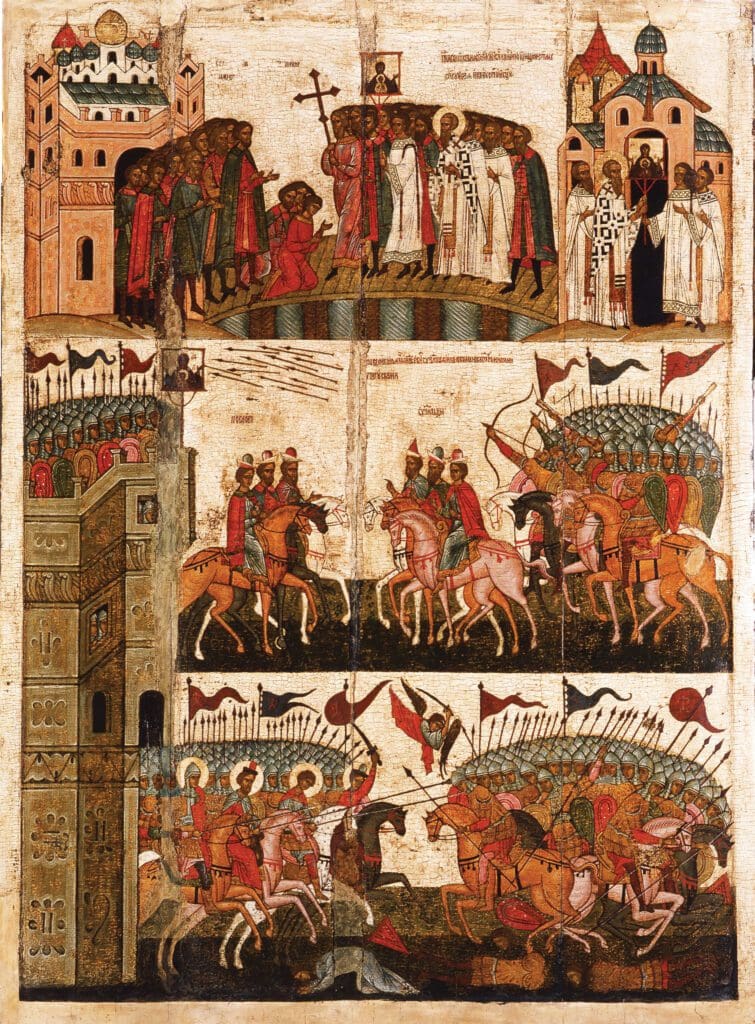

The eschatological doctrine of Rome as the last kingdom which protects the world from the Antichrist and will exist until the Second Advent, restraining chaos, is common to all Christian cultures. This empire has no constant temporal or spatial characteristics and can appear on the territory of different states (translatio imperii romani). In the Russian tradition, this concept is presented in the well-known historiosophic doctrine of Moscow as the Third Rome. It was authored by the monk Philotheus from the Belozersk Monastery in 1523–1524, and was officially recorded in the 1589 Founding Deed of the Council of Moscow, by which the Moscow Patriarchate was established.

‘The Soviet idea of protecting the working class from capital, and then, during the Second World War, the protection of humankind from the absolute evil of Nazism is interpreted nowadays by neoconservatives as a version of secular state messianism and Orthodox universalism’

The postulate that the Russian people are the chosen nation, and that their terrifying burden is to fight against the Antichrist, led to the formation of a particular form of governance in the Tsardom of Muscovy. Already during Ivan the Terrible’s reign, it was declared that the two enemies of Moscow as the Katechon are the external Antichrist, that is, all lands beyond Muscovy, and the internal Antichrist, which is no less dangerous than the external one. Internal resistance to the state under certain circumstances, and especially during unstable periods, is now interpreted as an indulgence to the powers of Anomia and chaos. This eschatological view becomes a constant of Russian history and the Russian understanding of the state as ‘the Restrainer’.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Christian idea of Katechon was reformulated in a secular foreign-policy context, but still with some elements of the providential mission of Russia as the protector of the world and the military ‘shield’ of Europe. For example, the statesman and greatest Russian poet of the eighteenth century Gavrila Derzhavin (1743–1816), in his ‘Ode on the Taking of Izmail’ (1791), addresses Europe thus:

‘[…] it’s Russian fate

To protect you from the Barbarian bonds,

To trample on Timurs,

To protect you from Umar’s muses,

To avenge the crusades,

To cleanse the Jordan waters,

To free the Holy Tomb,

To return Athena to Athens,

And Constantinople to Constantine,

And to establish peace for Japheth.’3

The idea of Russia as a ‘shield’ protecting Europe can be found in Alexander Pushkin’s letter of 19 October 1836 to philosopher Pyotr Chaadaev (1794–1856): ‘What concerns your ideas, you know that I do not agree with you on many points. Without doubt, the Schism separated us from the rest of Europe, and we did not participate in all the great events that stirred it, but we did have a special destiny. It was Russia and its limitless territory that absorbed the Mongolian invasion. The Tatars did not dare going to our Western borders, leaving us in their rear. They retired to their deserts and the Christian civilization was saved […] our martyrdom saved the energetic development of Catholic Europe all the trouble.’4

Another great Russian poet and statesman Fedor Tyutchev (1803–1873) also uses this ideologeme, for example, in the 1848 poem ‘Russian Geography’:

‘Moscow and Peter’s town, the city of Constantine,

these are the cherished capitals of the Russian monarchy.

But where is their limit? And where are their frontiers

to the north, the east, the south and the setting sun?

The Fates will reveal them to the future generation.

Seven internal seas and seven great rivers

From the Nile to the Neva, from the Elbe to China,

From the Volga to the Euphrates, the Ganges to the Danube,

This is the Russian empire and it will never pass away,

just as the Spirit foretold and Daniel prophesied.’5

Thus, the Greek and Roman idea of internal structure, an inner order of the inhabited world was transformed on Russian soil into the idea of defence from the external enemy. Russia sees itself not so much as an empire that holds the power of chaos beyond the borders of the world by its inner order, but rather as a military force that resists a metaphysical enemy, sent by the Antichrist. This metaphysical enemy takes different shapes in different historical periods: the Tatars, the Turks, Freemasons, Napoleon, Hitler, and nowadays NATO and ‘Ukrainian fascists’.

During the Silver Age, the idea of Katechon as a shield was once again reformulated, this time in an apocalyptic and decadent Eurasian context. Russia is under an intoxicating Dionysian influence and no longer restrains the Antichrist, but lets him into the fallen world because there is no hope of salvation any more. In this version, Russia lays the shield down and refuses to hold back the ‘pan-Mongolic’ movement, most vividly depicted in Aleksandr Blok’s ‘The Scythians’ (1918):

‘You are but millions. Our unnumbered nations

Are as the sands upon the sounding shore.

We are the Scythians! We are the slit-eyed Asians!

Try to wage war with us—you’ll try no more!

You’ve had whole centuries. We—a single hour.

Like serfs obedient to their feudal lord,

We’ve held the shield between two hostile powers—

Old Europe and the barbarous Mongol horde.

[…]

But if you spurn us, then we shall not mourn.

We too can reckon perfidy no crime,

And countless generations yet unborn

Shall curse your memory till the end of time.

We shall abandon Europe and her charm.

We shall resort to Scythian craft and guile.

Swift to the woods and forests we shall swarm,

And then look back, and smile our slit-eyed smile.

[…]

But we ourselves, henceforth, we shall not serve

As henchmen holding up the trusty shield.

We’ll keep our distance and, slit-eyed, observe

The deadly conflict raging on the field.

We shall not stir, even though the frenzied Huns

Plunder the corpses of the slain in battle, drive

Their cattle into shrines, burn cities down,

And roast their white-skinned fellow men alive.’6

‘The Katechonic discourse replacing Marxism will soon be the base of mandatory ideological education which is making a comeback in Russia’s higher education system’

The Soviet version of Katechonic messianism is an important topic which is beyond the limits of this article. I will only emphasize the fact that during the post-Soviet period, when the ideologeme ‘Moscow, the Third Rome’ re-emerged in Russian culture and politics, right-wing intellectuals started interpreting the Soviet, primarily Stalinist, period of Russian history as exclusively Katechonic. The Soviet idea of protecting the working class from capital, and then, during the Second World War, the protection of humankind from the absolute evil of Nazism, is interpreted nowadays by neoconservatives as a version of secular state messianism and Orthodox universalism.

One of the leading conservatives, Egor Kholmogorov (b. 1975) defined the Katechonic essence of Russia’s mission in the world as follows: ‘Russians always “defend”, even when it might seem that they attack.’7 Such an understanding of one’s own nation’s sacrifice in European and world history only reinforces the feeling of being insulted by the reluctance of European nations to acknowledge this difficult and at the same time sacral destiny of Russia. One of the topoi of Russian culture is the accusation of the West having ‘malicious intent’ against Russia, the popularity of conspiracy theories, and the search for internal and external enemies. Kholmogorov expresses the apocalyptic mood of the present moment and speaks about the readiness of Russians to ‘remove the lid’:

‘To be the third is a calling and an undisputable place of Russians in history. The meaning of this place is not to allow for “the fourth one” to come; we have to stand on a post, keeping off all the contenders for the Roman sceptre by kicks, clubs, and nuclear missiles […] any non-Russian, “fourth” idea will be the incarnation of evil and will result in a painful end of the whole world. This is how the Byzantine idea of Katechon is refracted in our imperial consciousness, the idea of withholding the world. That which stands on the bridge between the Antichrist and the world and which does not let the Antichrist into the world. Nowadays it is not a bridge but rather a manhole, the lid of which is removed from time to time, and some vampires, or werewolves or murderers come out of this hole. The Russian tarpaulin boot stamps on that lid, and restores the silence for some time. The crawling beast knows that if it shows itself too much, the Russian will not hesitate to blast it together with the whole world. Because “there shall not be the fourth one”, and if before us there was the Flood, after us there is only the Apocalypse.’8

The contemporary conservative discourse of Katechon originates not only in the Russian historiosophic tradition and Russian romantic nationalism, but also in the political theology of Carl Schmitt (1888–1985) who writes about Katechon in the chapter ‘The Christian Empire as a Restrainer (Katechon) of the Antichrist’ in his Nomos of the Earth (1950). For Schmitt, Katechon is also identical with the state; he understands it as a force that restrains chaos. The first Russian translations of Schmitt appeared in the 1990s. In radical conservative circles it was Aleksandr Dugin who popularized Schmitt’s ideas,9 and in a 1997 article entitled ‘Katechon and Revolution’10 introduced Schmitt’s approach. The Katechon narrative quickly became very popular in neoconservative circles, and lately is increasingly used in the media, reaching an ever-larger audience.

Atomic Orthodoxy: Russia’s Double Shield

According to the neoconservative concept, in order to fulfil the mission of Katechon, Russia needs to unite ‘the Reds’ and ‘the Whites’, marrying the nuclear shield of the Red Soviet tradition and the Orthodoxy of the White legacy. Orthodoxy thus becomes identical to the military-industrial complex, functioning as a shield and—therefore—as a guarantee of sovereignty. That is why, according to ideologues of the new Russian messianism, all attempts to diminish the role of the Orthodox Church must be punished (as for example Pussy Riot) because they represent not only an attack against Russian sovereignty but also a sign of the coming doomsday.

This concept of the two shields of Russia is known in post-Soviet conservative circles as the ideology of Atomic Orthodoxy. During a 2007 press conference, Putin was questioned by a journalist from Sarov, the city where the first Soviet nuclear bomb was created. The first question was about the future of Orthodoxy and the second was about the nuclear strategy of Russia. Putin replied as follows: ‘The two topics are related because both the traditional faith of the Russian Federation and the nuclear shield of Russia are the components that strengthen the Russian State and create necessary conditions for internal and external security of the country. This clearly means how the state has to treat both of them today and in the future.’11

Egor Kholmogorov developed Putin’s unification of Orthodoxy with the nuclear shield as the doctrine of Atomic Orthodoxy.12 Here are some of the main points of this ideology:

‘First: the religious and historical mission of Russia is to secure the best possible conditions for the Russian and Orthodox people.

Second: in order to fulfil this mission successfully, Russia cannot be an Orthodox state only; it should be a powerful state so that nobody and no weapon could silence our testimony of Christ.

Third: to develop the most perfect military, organizational, and other means to protect our sovereignty is not only a military-political but also a spiritual goal, in which the secular and the sacral are going hand in hand.’13

According to Kholmogorov, the post-Soviet Russian identity must include both Soviet technocratic elements and Christian Orthodox ones. His main thesis is close to Prokhanov’s ‘Fifth Empire’ doctrine, considering the Soviet civilization as a logical stage of Russia’s Orthodox civilization, and declaring that the modern state has to use both resources—the Orthodox tradition and the best elements of the Soviet period. For Kholmogorov, Prokhanov, and many other conservative ideologists, the development and strengthening of the military shield of Russia is a question of agyopolitics, a question of a spiritual nature. That is why the fact that the first atomic bomb was created on the territory of the Sarov Monastery (on Stalin’s orders) is interpreted as God’s providence, and the clarification of St Seraphim’s14 image is compared with the flash from a nuclear explosion.

Russia as ‘Europe without the West’

Neither the anti-Western rhetoric nor the aggressive illiberalism of Russian conservative communities presuppose an anti-European position. It is actually the other way round. Russian cultural policy after the annexation of Crimea differs not only in its stricter control over cultural activities, but also in its much more distinct ideological line, which presents Russia as the main protector of ‘European’ Christian civilization. In this ideological construct, the terms Europe and the West are split: ‘the West’ is defined as liberal multiculturalism, in which Europe’s Christian foundations are suppressed. In the search for a national identity, priority is accorded to anything portraying Russia as a guardian of the classical European tradition and as the ‘true’ Europe, a European Christian civilization rooted in Greek and Roman culture.

A series of events in cultural life demonstrate the efforts of authorities working on the new project of ‘Russo-European civilization’ and the changes in official cultural policy of recent years that are directly connected with shaping the image of Russia as the ‘guardian and defender’ of European Christian civilization. In order to strengthen Russia as Katechon in its battle against the powers of Anomia, conservative ideologists propose the unification of European traditionalists in their fight for Christian values and the foundations of European civilization. They interpret Putin’s meeting with Pope Francis in November 2013 as an attempt to find allies among the Christian powers in Europe. Nataliia Narochnitskaia, the conservative politician, historian, and a member of the Izborsk Club, notes:

‘The current situation shows that in our common European Christian civilization, there is an avalanche of such tendencies as de-Christianization, change of guiding principles, the confusion of sin and virtue, beauty and ugliness, truth and lies. […] The times set new tasks before Catholics and the Orthodox people: to be united in order to preserve the great Christian legacy and its values and morals, primarily such as faith, motherland, honour, duty, love. All the values that were born through the Christian idea and were incorporated in the life and history of European nations experience a great pressure nowadays.’15

Conclusion

The Katechonic discourse replacing Marxism will soon be the base of mandatory ideological education which is making a comeback in Russia’s higher education system. This new ideological curriculum is overseen by Sergey Kiriyenko, first deputy head of the President’s Administration. The main outlines of the new ideological curriculum were established at the ‘Russia’s DNA’ conference held on 26 October 2022 in Sochi. This ideological curriculum will be subdivided into four modules:

The elaboration of the main ‘historical’ module is likely to be entrusted to Vladimir Medinsky, the former Russian minister of culture, and current assistant to the President.

The second module called ‘Cultural Code’ will probably be entrusted to Mikhail Piotrovsky, director of the State Hermitage in St Petersburg.

‘Russia in the World’ is to be overseen by the political scientist Sergey Karaganov.

‘Envisioning a Future’ might be assigned to Mikhail Kovalchuk, the current head of Russia’s leading institution for nuclear research—the Kurchatov Institute.

The rhetoric of spiritual mobilization, of Russia’s responsibility for the fate of the world, and of the ‘burden of the Russian people’ is becoming dominant once again as it was many times before during tragic periods in Russian history. Economic sanctions and diplomatic isolation as the punishment for the annexation of Crimea and the war in Ukraine are interpreted by the Russian regime and the majority of Russians as confirmation of progressing Anomia in the West, and will strengthen the Katechonic argument.

NOTES

1 ‘Medvedev Says Russia Is Fighting a Sacred Battle against Satan’, Reuters (4 November 2022), www.reuters.com/article/ukraine-crisis-russia-medvedev-idCAKBN2RU0GQ.

2 Bible Hub, https://biblehub.com/2_ thessalonians/2-3.htm.

3 Г.Р. Державин, Стихотворения (1790–1791) (author’s translation), https://rvb.ru/18vek/derzhavin/01text/031.htm.

4 Aleksandr Pushkin, Sobranie sochinenii, Vol. 10 (Moscow: GIKhL, 1962), 307.

5 Fedor Tyutchev, ‘Russian Geography’, transl. by F. Jude, in Andrew Baruch Wachtel and Ilya Vinitsky, eds, Russian Literature (London: Polity Press, 2009), 97. 6 Aleksandr Blok, ‘The Scythians’, transl. by Alex Miller, All Poetry, http://allpoetry.com/poem/8490607-The-Scythians-by-Aleksandr_Aleksandrovich_Blok.

7 Egor Kholmogorov, Russkii proekt. Restavratsiia budushchego (Russian Project. The Restoration of the Future) (Moscow: Algoritm, 2005), 280.

8 Kholmogorov, Russkii proekt, 18–19.

9 In the article ‘Carl Schmitt: Five Lessons for Russia’ (1991), Dugin writes: ‘The true national elite has no right to leave its people without the ideology which should express not only what it feels and thinks about but also what it does not feel and does not think about, and what they have been devoutly adoring, keeping it secret even from themselves, for thousands of years. If we are not able to arm the State with our ideology, the State which can be temporarily taken from us by “alien elements”, then we will by all means arm the Russian Partisan.’ Aleksandr Dugin, Konservativnaia revolutsiia (Conservative Revolution) (Moscow: Arctogeia, 1994).

10 Aleksandr Dugin, ‘Katechon and Revolution’, in Tampliery Proletariata (Moscow: Arctogeia, 1997), http://my.arcto.ru/public/templars/kateh.htm.

11 Vladimir Putin, Press Conference on 1 February 2007, http://lenta.ru/articles/2007/02/01/putin/.

12 The term ‘Atomic Orthodoxy’ originates from the title of Alexey Belyaev-Guintovt and Andrei Molodkin’s painting from the cycle Novonovosibirsk (1999), which depicts a deeply frozen Russia and where the rudder of the missile submarine resembles a cross. For more on Belyaev-Guintovt and imperial aesthetics in contemporary Russian art, see Maria Engström, ‘Forbidden Dandyism: Imperial Aesthetics in Contemporary Russia’, in Peter MacNeil and Louise Wallenberg, eds, Nordic Fashion Studies (Stockholm: Axl Books, 2012), 179–99; and Maria Engström, ‘Military Dandyism, Cosmism, and Eurasian Imperart’, in Birgit Beumers, ed., Russia’s New Fin de Siècle: Contemporary Culture between Past and Present (Bristol: Intelect, 2013), 99–118.

13 Egor Kholmogorov, ‘Atomnoe pravoslavie. Sarovskaia lektsiia’ (Atomic Orthodoxy. The Sarov Lecture), Specnaz, 7 (2007), www.specnaz.ru/article/?1118.

14 Seraphim of Sarov (1754–1833) is one of the most renowned Russian saints and is venerated in the Eastern Orthodox Church. He is generally considered the greatest of the eighteenth-century startsy (elders).

15 Pyotr Akopov, ‘Chetvertyi visit k tret’emu pape’ (The Fourth Visit to the Third Pope), Vzgliad (26 November 2013).

Related articles: