Economic Opportunities for and Created by the Central and Eastern European Region

The fundamental architecture of the international monetary and trade system was laid down in the aftermath of the Second World War, which set the stage for intense trade and investment relations among states and their economies.1 Based on these international legal foundations, economic globalization began to take off in the 1970s.2 With the collapse of the centrally planned economies at the end of the 1980s, it also found its way with relative ease into former communist states, including the countries of the Central and Eastern European (CEE) region.3 The rapid development of transportation and communication technology throughout the twentieth century also contributed to shifting most industry, especially labour-intensive production, to a global scale.4

That has led to the creation of various forms of transnational business relations.5 Most globalized production processes have been ever more narrowly subdivided, and now take place in a contractual ecosystem called coordinated supply chains. They are now the backbone of the system of economic globalization that has come to dominate the global economy over the past three decades. They power 80 per cent of world trade, 60 per cent of global production, and sustain over 450 million jobs.6 One out of every seven jobs worldwide is global supply chain related.7 Therefore, managing a fragmented and geographically dispersed web of affiliates, contractual partner firms and arm’s-length transactions in a harmonious way now constitutes the primary element in the competitiveness of a transnational corporation.

Although low-cost manufacturing has provided the main impetus for different supply chain formations, various events over the past decade have demonstrated the vulnerabilities, as well as the increased risks and costs, of global operations. These range from the risks associated with the loss of control over

offshored productions, to external threats, to the harmful impacts of operations on local communities. The coronavirus pandemic and its impact on supply chains has amplified this trend. In a broader context, it also reveals the downsides and limitations of economic globalization. This trend has recently given way to a greater emphasis on safeguarding economic sovereignty, and also sets the stage for various realignment efforts within the global supply chain known as ‘reshoring’, ‘near-shoring’, or more recently ‘right-shoring’.

This article aims to outline the nature and role of global supply chains in economic globalization, and to highlight the underlying roots of and reasons for the new trend towards realignment (sections I–II). Based on this conceptual framework and through concrete business examples, the authors also intend to explore the potential opportunities within this trend that CEE countries, including Hungary, might exploit (section III).

‘Although low-cost manufacturing has provided the main impetus for different supply chain formations, various events over the past decade have demonstrated the vulnerabilities’

I. The Nature, Advantage, and Rise of Global Supply Chains

The adoption of international economic regulation such as trade and investment agreements allowed businesses to offshore part or all of their production to various countries around the world. Rapid developments in maritime transportation and communication soon rendered this theoretical opportunity a practically useful and viable business solution. Outsourcing to countries that have either lower labour costs or more lenient business regulations could allow manufacturers to save production costs and therefore gain competitive advantage both on the home market and elsewhere. This type of cost savings serves as the major incentive to global supply chain formations.8

This trend has led to the solidification of transnational business relations along with the rise of transnational corporations.9 A transnational corporation may seem one single entity in a business sense, like the ‘Total group’; however, it might consist of several hundreds or even several thousands of separate legal entities. John G. Ruggie differentiates between two types of transnational (multinational) enterprises from an economic perspective: actor-based and network-based transnational enterprises.10 According to

the actor-based view, the ‘group’ consists of the lead firm and its subsidiaries or equity affiliates, which mostly reflect an ownership relation. The network-based view includes even more companies in the group that are all part of the business strategy of the transnational corporation. In addition, the ‘contractual

ecosystem’ that contains various suppliers is an even broader concept. For example, in order to produce the famous iPhone, Apple used 785 suppliers in 31 countries in 2014.11 It clearly shows that one of the fundamental characteristics of transnational business entities is the ability and aspiration to fine-slice activities and operations in their supply chains and settle them in the most cost-effective location, both domestically and globally.12

This characteristic sheds light on two fundamental ideas of supply chain management. On the one hand, almost every product is a result of the cumulative collaboration of multiple companies located around the world. They form a coordinated and complex supply chain.13 On the other hand, a firm cannot achieve or maintain competitiveness unless it is able to look beyond the ‘four walls’ of its factory and manage and optimize the operation of their entire supply chain. That has become a key factor in maintaining a competitive edge in the globalized economy.

Competitiveness has largely become equated with seeking lower cost manufacturing. This has been driven by the continued pressure to purchase and sell products at the lowest possible price, and this trend has been encouraged by the end consumers, who are willing to pay only the lowest price at large

brands and retailers. Offshoring has therefore been a process whereby companies move their manufacturing to low-cost regions and countries (hereinafter, LCC) such as Vietnam, Thailand, and Taiwan, to take advantage of predominantly low labour costs and lax regulation, and then to ship the products back to the home country or around the world by ocean freight. Therefore, consumption on the basis of low cost and price has become the predominant driving force of the offshoring trend.14 In line with this trend, one recent survey shows that around 70 per cent of decisions to buy imports are driven by price.15

Another recent survey, conducted by the management consulting firm Kearney, reported increasing and record high imports into the US, especially from LCC in Asia, until 2018.16 This is underpinned by wide supplier networks. For example, a vast web of suppliers participate in Walmart’s supply chains, with over 20,000 located in China alone. Nike relies on 8,000 suppliers spread across 51 countries.17 The French Total group consists of nearly 900 subsidiaries and equity affiliates, but has more than 16,000 outlets in 110 countries. Even though they are all separate legal entities, they act as one company under a unity of command, single global vision, and business strategy optimizing worldwide operations for efficiency, market share, and profits. They exist in the everyday world of economic activity.18

Efficiently managed global supply chains thus have the ability to exploit low labour costs, along with other production cost savings associated with regulatory requirements—such as environmental or labour regulations—that are more lenient in overseas countries. That type of business strategy seeks to increase competitiveness while reducing costs. However, utilizing centralized production facilities in faraway places exposes companies—as well as countries—to dependency, along with various other risks.19 This has disruptive and damaging impacts on the harmonious operation of supply chains. The significant disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic clearly revealed and amplified the downsides of offshored production. At the same time, however, they also shed light on an unfolding series of events that ultimately indicate the limits of this type of business strategy and economic globalization in a broader sense.

II. The Vulnerabilities and Downsides of Global Supply Chains

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically highlighted the underlying vulnerabilities of global supply chains. As a result of worldwide factory shutdowns and ‘stay home’ orders, the pandemic has had major impacts and ripple effects on the process of procuring and shipping products from overseas.20 Companies that previously built and relied on complex global networks, designed to minimize cost and maximize efficiency, were all of a sudden left without any alternative means of keeping their business operational. The inability to obtain goods, or a significant delay in the procurement process, translated into significant economic losses.21 Moreover, attempts to restart disrupted global supply chains often take several months, and likewise entail significant additional costs.

‘The significant disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic clearly revealed and amplified the downsides of offshored production’

In addition, the most vulnerable supply chains often turned out to be those that supplied basic needs or health and safety supplies to local populations during public health crises: personal protection equipment, medical supplies, or pharmaceutical supplies. One lesson of the pandemic is that under such circumstances countries seek to control the production and distribution of these health and safety supplies, and thus—by disrupting supply chains—take steps to ‘command and control’ the medical and personal protection equipment markets. In turn, this highlighted the exposure and dependency not only of companies, but also of countries and their populations, to the vulnerabilities of the supply chains for vital necessities in times of crisis.

The experience of the pandemic underscored that the price of extracting cost savings by offshoring production is a loss of control. This loss of control over the operation of the supply chain has two principal consequences. Firstly, reliance on a single faraway supplier leads to increased exposure to geopolitical risks and other uncertainties in the operation of the lead company. Additionally, it leads to the erosion of the economic sovereignty of the home country and ultimately undermines it. The immediate lessons learned from the impacts of COVID-19 is that ‘shorter’ supply chains provide better and more reliable control, and can thus respond more quickly and flexibly to the needs of the end customers. In addition, the recent pandemic was only the tip of the iceberg, showing that global supply chains are fragile and potentially exposed to even more critical shocks.

Among the shocks that endanger the smooth operation of long supply chains is the increasing number of cyber-attacks. Due to widespread digitization, the management of supply chains depends on electronic systems to an increasing extent.22 Many industries are therefore exposed to these types of attacks, which are the result of either malicious non-governmental action or geopolitical friction. The cyber-attack against the Colonial Pipeline well illustrates the potential magnitude of these attacks. The largest fuel pipeline in the United States that carries gasoline and jet fuel from Houston, Texas, to the Southeastern United States was hacked in May 2021. The shutdown of this vital infrastructure led to a shortage of fuel on the East Coast of the US, which not only compromised the operation of the company but, by crippling traffic, endangered the wider population and security situation in a large part of the country. Accordingly, the federal government declared an emergency and experts warned that the shutdown could have a ripple effect well beyond the US.23 This clearly shows the need to consider the security aspects of building supply chains, and to develop additional information security systems. However, that naturally entails large potential cost implications, which reduce the labour cost advantage of outsourced overseas

operations.

Beyond cyber-attacks, accidents can also have disastrous impacts on the smooth and timely—or ‘just-in-time’—operations of global supply chains. Offshored production requires long-distance shipping that frequently passes through bottlenecks such as the Suez Canal. Around 13 per cent of goods making up the global trade volume pass through the 193-kilometre-long Suez Canal.24 The accident of the Ever Given cargo ship in March 2021 blocked the channel in both directions for six days. While this does not seem a long pause in everyday terms, to supply chains accustomed to operating in a ‘just-in-time’ system, this maritime traffic jam—partly caused by the ever increasing size of cargo ships—proved a ‘nightmare’ scenario, leading to disruptions that lasted several months. Smaller ports cannot absorb this scheduling conflict, since instead of docking, container ships of this size load their cargo onto smaller ships at major hubs, and these smaller ships sail into ports.25 The insurance company Allianz estimated that each day of the blockade cost between six and ten billion US dollars.26 As such, these supply chain bottlenecks reveal additional costs that offset the advantages of offshore productions.

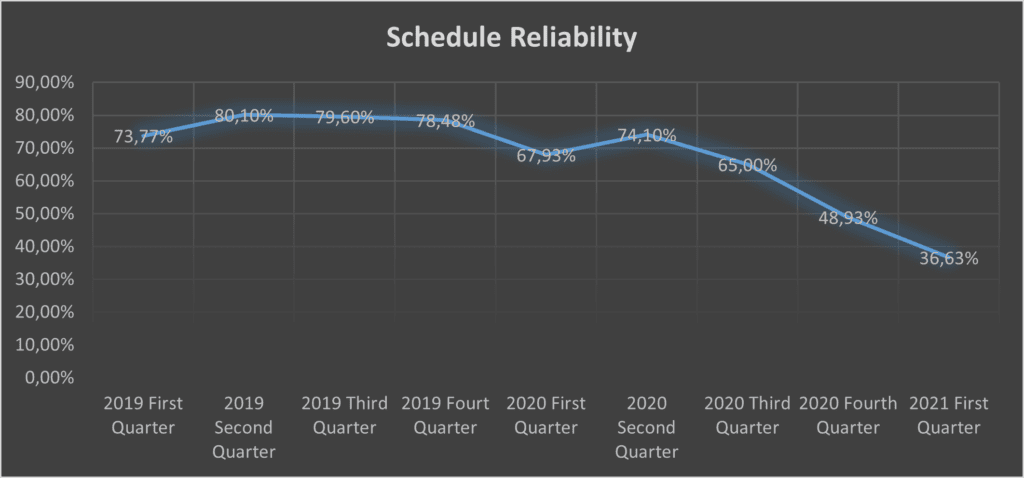

In a broader context, the rising costs and weakening schedule reliability of sea transportation are also considered as a source of risk. A forty-foot long container currently costs approximately 9,000 US dollars to transport from Shanghai to Hamburg, while its cost was approximately 1,500 USD a year ago. One would have expected the quality of the service to have improved along with the cost, but the reality is quite the opposite. Global schedule reliability has decreased from 80 per cent to 40 per cent. Heavily congested sea lanes have become widespread, likewise endangering and upending production processes that rely on ‘just-in-time’ systems.27 So, companies get much less while paying five times more.28 The above chart shows how the global reliability of transportation has been decreasing ever more rapidly pace over the last two years.

Dependency is another source of risk in industrial supply chains. Reliance on a critical supplier in a single country or region increases geophysical and political risks. An excellent example of this is semiconductors, which are a key element in all types of electronics, and are thus indispensable for producing vehicles, aircraft, weapons, and many other electronic devices. The production of semiconductors is largely outsourced to Taiwan, and produced by a single company, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). Thus, a shutdown of this company will have ripple effects across the entire world economy. As such, it creates risk by dependency. In addition, it also has serious strategic implications, since countries can no longer produce essential products domestically.29 Abandoning that capability

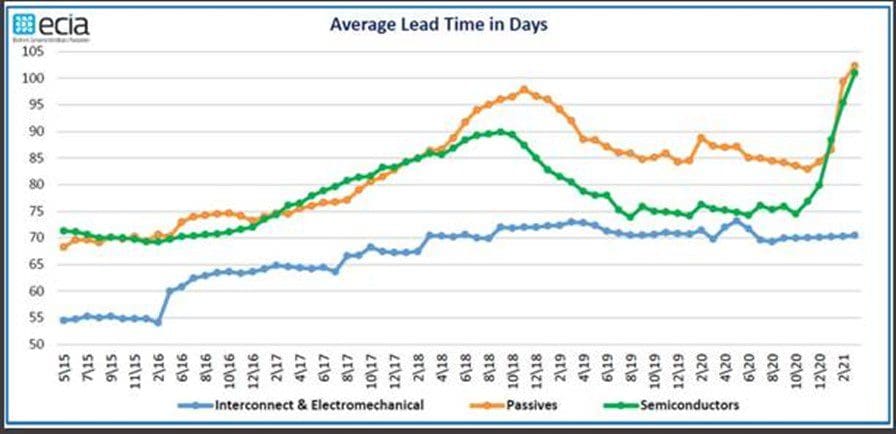

has long-term implications for economic sovereignty. In general, the dependency of the electronic industry on Asia has grown massively over the last twenty years. On top of that, there have been major setbacks regarding the availability of electronic components since the coronavirus pandemic broke out. The lead-time for key passive components has increased from the usual 16 to 24 weeks to 24 to 36 weeks.30 The situation is even worse for complex electronic components such as drivers, with orders currently being fulfilled in 26 to 52 weeks. Companies have to book parts today to be able to have deliveries from Asia in early 2022. The following chart shows that lead times had begun to increase gradually even before the COVID-19 pandemic broke out.

In a similar vein, providing raw material has been a challenge for Europe for some time. Therefore, the European Parliament began to work out a resilience package for 14 materials in 2011. Not surprisingly, this list had grown to include 30 materials by 2020.31 A relatively recent and local example of the availability difficulties of raw materials is that of Škoda Auto, which has been forced to slow down or even halt production due to the lack of electronic chips.32

‘Cost savings at the expense of violating international human rights, environmental and other legal norms, amount to a type of unfair competition that seeks to benefit from the lack of level playing field and from regulatory lacunas’

Furthermore, the loss of control can also lead to abuse of labour or other violations of international legal standards. The underlying logic of developing global supply chains is to extract cost savings by exploring regions with lower labour costs and more lenient regulations than those of the home countries. As such, it allows manufacturers to save money while rendering the human, environmental, and other costs invisible.33 This creates a regulatory ‘race to the bottom’ in LCC, and companies are inclined to exploit gaps in the regulations of this competitive global marketplace.34 Economic globalization has been marred by grave rights violations, from the operations of Shell in Nigeria to the collapse of the Rana Plaza in Bangladesh in 2013.35 That phenomenon has widespread and far-reaching consequences. Cost savings at the expense of violating international human rights, environmental and other legal norms, amount to a type of unfair competition that seeks to benefit from the lack of level playing field and from regulatory lacunas.36 Recent efforts in international law, such as the adoption of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights in 2011 and other initiatives aim to reduce this type of business behaviour. Against the backdrop of these international initiatives, several countries, including France37 and Germany,38 have either already introduced or seek to introduce domestic legislation on supply chains that require companies to identify and mitigate risks to human rights along their supply chains. That legislative trend, of course, also reduces the cost advantages LCC can offer for offshore production. On the other hand, this type of unfair competition has led to a decline in working-class wages while at the same time undermining the manufacturing and industrial bases of Western countries. This trend has political ramifications that have raised awareness of the importance of economic sovereignty and ultimately led to the recent trade war on tariffs.39 That also translates into disruptions and additional costs for supply chains.

Currency volatility was already a source of risk before the COVID-19 pandemic. Each company has to plan reserves considering exchange between USD, euro, and RMB. And last but not least, the rapid development of digitization and the associated technological revolution will certainly have an impact on global supply chains too. Supply chain digitization can further improve their operations and make them more efficient by eliminating the time as well as the potential errors of human decision-making. However, cost efficient and widely available automation has the potential to reduce or even replace the incentive for low cost labour, which would also allow the development of regional supply chains. Therefore, using these types of technologies, companies might be able to regain the locus of control over localized and regionalized supply chains without facing high and thus less competitive labour costs. Whether the latest achievements of digital technology will bring about major shifts in global supply management also turns on their availability and costs.40

Consequently, the increased costs associated with the loss of control over the operation of global supply chains can have the potential to offset higher labour costs and prompt businesses to consider strategies like ‘reshoring’, ‘nearshoring’, or ‘right-shoring’.

III. ‘Reshoring’, ‘Nearshoring’, or ‘Right-Shoring’: Opportunities for the Cee Region

Considering the trade-off between low cost labour and an increased locus of control, companies have been seeking to apply strategies that bring back (‘reshore’) or regionalize (‘nearshore’) their supply chains. Both ‘reshoring’ and ‘nearshoring’ could provide the considerable advantages of lower transportation costs, as well as shorter lead times between design, production, and final sales, enabling more ‘just-in-time’ production.

In the United States between 2010 and 2018, 749,000 jobs were brought back to the country across 2,900-plus companies as a result of ‘reshoring’. Intel, General Electric, and Boeing are amongst the manufacturers that brought back the most jobs.41 A recent survey conducted by Kearney in March 2021 shows that almost half of the interviewed manufacturing executives agreed that the benefits of onshore production outweighed the higher labour costs, and said that their company would strive to diversify its supply chain over the next three years to reduce dependence on a single country source or manufacturing location. Many executives find that ‘nearshoring’ to Canada or Mexico is even more advantageous, as it offers proximity to the US market and thus shortens supply chains.42 With regards to policy framework, the previous and current administrations are committed to vigorous government intervention to support domestic manufacturing, especially in areas that are strategically vital to national interests. A current bill, the so-called Help Onshore Manufacturing Efficiencies for Drugs and Devices (HOME) is an example of a law intended to encourage domestic manufacturing of critical drugs and devices to address economic, health, and security concerns, combat shortages, and promote increased domestic diversification of, and independence from, foreign reliance.43 An example is Intuitive Surgical, a leading developer and producer of robotic-assisted surgical equipment that keeps their supply chain within a 400-mile radius to make sure that their intellectual property is protected and the value chain is under their full control.

European countries also face the challenge of developing resilient supply chains for industrial ecosystems within the European Union. From a strategic standpoint, it is essential for European companies to reduce their dependency on raw materials, components, and finished goods from overseas. ‘Reshoring’ back to Europe could be a viable option, although companies are likely to be worried about cost increases and the scarcity of their tight resources to run all these ‘reshoring’ projects.

‘The production of FFP2 and medical masks is a great example. Since the high-volume textile industry has almost entirely left Europe, every member state of the European Union is dependent on sources in Asian countries’

However, the CEE region has a lot to offer, including a skilled and experienced labour force at an affordable cost. For example, fully loaded minimum wage in V4 countries is around 550–600 euros per month.44 In this spirit, for example, the 125-year-old Hungarian innovative technology company Tungsram decided to offer a package for companies attempting to reduce their dependency on Asia. This concept is called ‘Company in a Box’. Tungsram offers assistance to enterprises that are seeking to move their supply chains back to Europe by offering a wide range of services and facilities in Hungary. The scope of this support includes laboratory equipment and services, world-class manufacturing, financial, IT, HR, and legal consultancy, as well as involvement in research and development projects, and access to the company’s global distribution network. The Hungarian Investment Promotion Agency is partnering with Tungsram in this initiative, and is ready to provide investment incentives through the Exim Bank. In Hungary alone, there are 1,300 green and brown field sites available.45

Corporate income tax is 9 per cent and social contribution tax is 15.5 per cent, which place the country among the most competitive in the EU. Cooperation with various universities and vocational training centres ensures a large talent pool going forward. In addition, available land and production facilities can

significantly reduce the time and cost of ‘reshoring’, which are the biggest barriers. As a result, the ‘Tungsram Ecosystem’—with trusted suppliers, governmental relationships, a high quality labour force, universities, and vocational centres—provides immediate assistance in ‘reshoring’ in a timely and cost-effective manner.

The production of FFP2 and medical masks is a great example. Since the high-volume textile industry has almost entirely left Europe, every member state of the EU is dependent on sources in Asian countries. Governments were ready to pay extra for masks for immediate delivery. In order to reduce exposure, investments were highly supported and local testing laboratories were set up. Production lines were ordered from Asia and there was competition to secure raw material. Roughly six months later, significant

capacity was ‘reshored’. Unit prices went back to normal so that ordinary citizens could afford to buy as many masks as they needed. As part of the modernization of the Hungarian Army, there is an initiative to ‘reshore’ production and development back to Hungary. Tungsram Group entered into cooperation with the Modernization Institute of the Hungarian Army to develop and produce state-of-the-art ceramics for personal and vehicle protection for the EU.

In the face of various supply chain vulnerabilities, the American and European experiences and examples point to the need to explore various ‘reshoring’ and ‘nearshoring’ strategies. Yet the companies’ strategic options cannot be narrowed down to a mere binary choice between ‘offshoring’ and ‘reshoring’. Recent studies have shown that a more comprehensive approach, so-called ‘right-shoring’ would be more valuable to guide companies seeking to source raw materials or manufactured products. The ‘right-shoring’ decision framework explores a wide range of variables, taking into account economic, political, legal, geographic, and ecosystem considerations.46 This more comprehensive approach seeks to fully embrace the complexity of the choices regarding how to realign supply chains, and thus becomes a key tool for businesses seeking to maintain competitiveness while mitigating risk in the coming decades. It can also help governments forge industrial policies to exploit the opportunities created by shifting supply chain architectures, and thus better serve both the well-being and security of their populations.

IV. Conclusion

Global supply chains are the backbone of economic globalization, providing businesses with the ability to narrowly subdivide their operations across multiple locations that afford cost advantages. However, the competitive edge secured by offshoring to LCC has come with a heavy price, and exposes companies to various risks. As well as outlining the nature and rise of global supply chains, this paper has explored their underlying vulnerabilities, which have been dramatically exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Among the risks that pose challenges to global supply chains, the authors identified the loss of locus of control; the harmful effects suppliers have upon local communities; cyber attacks and accidents that cause damage to individual links in the chain; rising costs and lead times, congestion and weakening schedule reliability in maritime transportation, and dependency on one critical supplier in a single country; as well as the rise of digitization that is continuing to reduce or even eliminate the need for low cost labour.

Damage to one link endangers the reliability and responsiveness of the entire chain, which is a crucial condition for the success and competitiveness of this type of business strategy. Furthermore, as the COVID-19 pandemic has clearly shown, supply chain disruptions can have detrimental impacts on the well-being and even on the security of the lead company’s populations, especially in areas of vital strategic national interest. Consequently, these vulnerabilities have the potential to offset the expected advantages of low-cost offshoring. The reduced incentives to offshore have recently led businesses to explore strategies such as ‘onshoring’, ‘nearshoring’, or ‘right-shoring’, and have also encouraged governments to shape their industrial policies to induce and exploit these shifts.

Both US and European companies have become more agile in responding to these shifting environments, and are in the process of seeking out options to guard their supply chains against various risks. The CEE region qualifies as an optimal location for ‘nearshoring’ or ‘right-shoring’ in a timely and cost-effective manner by offering a skilled and experienced labour force at affordable costs. Low taxes, less red tape, good infrastructure, and a developed academic ecosystem elevate this region, including Hungary, to amongst the most competitive in Europe. The future competitiveness of European companies will, to a large degree, depend on their willingness and capacity to harness the advantages the CEE region offers for regionalized supply chains within the EU.

NOTES

1 As a result of the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, the participating States established the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, along with the International Monetary Fund, which collectively serve as the fundamental institutions for international commercial and financial relations. For the role of the international financial institution in the post-war era, see Walter Isaacson et al., The Wise Men. Six Friends and the World They Made (Simon & Schuster, 2012).

2 The provisions for trade were originally set out in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, as well as in regional free trade agreements, which set the terms of international trade while the growing web of mostly bilateral investment treaties provided the rules and institutions for the protection of foreign businesses.

3 The liberalization process began even before the change of regimes in the Central and Eastern European countries, which were among the first to conclude international investment treaties on topics such as human rights, the military, or European association agreements. Rapid economic transformation, so-called ‘shock therapy’ was the priority for these countries. The consequences of this mindset were well illustrated in a The New York Times article from the 1990s on the influence of foreign investors in this region: https://www.nytimes.com/1992/06/21/business/czechoslovakia-s-wall-street-brigade.html, accessed 6 June 2021. See also Joseph E. Stiglitz, The Roaring Nineties. A New History of the World’s Most Prosperous Decade (W. W. Norton & Company, 2014).

4 For example, the seemingly simple invention of the ‘container’ reshaped the world economy once and forever: ‘The History of Containers’, https://www.plslogistics.com/blog/the-history-of-containers, accessed 6 June 2021.

5 These business relations include, among others, trade, intellectual property licensing, and capital investment. See e.g., Richard Schaffer et al., International Business Law and Its Environment (Cengage Learning, 2015), 2–11.

6 Robert C. Bird et al., ‘From Suspicion to Sustainability in Global Supply Chains’, Texas A&M Law Review, 7 (2020), 384–388.; UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2013: Global Value Chains: Investment and Trade for Development (Geneva: United Nations Publication), 135.

7 ILO (International Labour Organization), World Employment and Social Outlook (Geneva: ILO, 2015).

8 Sean A. Pager et al., ‘Redeeming Globalization through Unfair Competition’, Cardozo Law Review,

41 (2020), 2441.

9 To study the impact of transnational corporations on development and on international relations, the UN General Assembly created the UN Commission on Transnational Corporations as early as 1974 (UN Doc. E/5570/Add. 1, 1974), which signalled the beginning of the regulatory challenge nearly half a century ago.

10 John G. Ruggie, ‘Multinationals as Global Institution: Power, Authority and Relative Autonomy’, Regulation & Governance (2017), 2–3.

11 Ruggie, ‘Multinationals as Global Institution’, 3.

12 UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2013: Global Value Chains: Investment and Trade for Development (Geneva: United Nations Publication), 135.

13 See e.g.: John T. Mentzer et al., ‘Defining Supply Chain Management’, Journal of Business Logistics, 22 (2001), 1–3.

14 See ‘What We Are Seeing Now Is a Movement towards the Localization of Supply Chains. Conversation with Professor Robert Handfield’, https://precedens.mandiner.hu/cikk/20210620_what_we_are_seeing_now_is_a_movement_towards_the_localization_of_supply_chains_conversation_with_robert_handfield, accessed 21 June 2021.

15 Steve Moul, ‘Reshoring: COVID-19’s Impact on the Supply Chain’, Supply Chain Management Review (10 June 2020), www.scmr.com/article/reshoring_covid_19s_impact_on_the_supply_chain, accessed 7 June 2021.

16 Patrick Van den Bossche et al., ‘Global Pandemic Roils 2020 Reshoring Index, Shifting Focus from Reshoring to Right-shoring’, Kearney Research Report, https://www.kearney.com/operations-performancetransformation/us-reshoring-index, accessed 7 June 2021.

17 Bird et al., ‘From Suspicion to Sustainability’, 390.

18 Ruggie, ‘Multinationals as Global Institution’.

19 See ‘Rethinking Global and Local. Conversation with Professor Lorena Mathien’, https://precedens.mandiner.hu/cikk/20210604_rethinking_global_and_local_conversation_with_lorena_mathien, accessed 7 June 2021.

20 ‘Rethinking Global and Local’.

21 See ‘Strong Economies Built on Manufacturing, Conversation with Professor Lynn Fish’, https://precedens.mandiner.hu/cikk/20200918_strong_economies_are_built_on_manufacturing, accessed 7 June 2021.

22 Matthew Warren et al., ‘Cyber Attacks against Supply Chain Management Systems: A Short Note’, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 30/7–8 (2000), 710–716.

23 See https://www.computerweekly.com/news/252500508/Colonial-Pipeline-ransomwareattack-has-grave-consequences, accessed 9 June 2021.

24 See https://www.dw.com/en/opinionsuez-canal-blockage-reveals-globalizationbottlenecks/a-57040234, accessed 9 June 2021.

25 See https://www.cnbc.com/2021/03/29/suez-canalis-moving-but-the-supply-chain-impact-could-lastmonths.html, accessed 9 June 2021.

26 See https://www.dw.com/en/opinionsuez-canal-blockage-reveals-globalizationbottlenecks/a-57040234, accessed 9 June 2021.

27 See https://www.handelsblatt.com/unternehmen/handel-konsumgueter/corona-us-konsum-chinasexport-boom-just-in-time-funktioniert-zurzeit-nichtrekordstau-an-containerschiffen-stuerzt-welthandelins-chaos/27286510.html, accessed 21 June 2021.

28 See https://www.lme.com/, accessed 24 June 2021.

29 ‘What We Are Seeing Now Is a Movement towards the Localization of Supply Chains. Conversation with Professor Robert Handfield’.

30 See https://www.ecianow.org/stats, accessed 22 June 2021.

31 See https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0474, accessed 24 June 2021.

32 See https://www.scmonitor.hu/hir/20210625/korlatozni-kenyszerul-termeleset-a-cseh-skodaautogyar, accessed 24 June 2021.

33 Pager et al., ‘Redeeming Globalization’, 2438–2444.

34 The concept of the ‘race to the bottom’ was used by the late Justice Louis Brandeis to describe the phenomenon of regulatory competition that reduces standards (Louis K. Liggett Co. v. Lee, 288 US 517, 1933). See also Adolf Berle et al., The Modern Corporation and Private Property (Routledge, 1991).

35 See John Ruggie, Just Business. Multinational Corporations and Human Rights (W. W. Norton & Company, 2013).

36 Pager et al., ‘Redeeming Globalization’.

37 ‘Loi No. 2017-399 du 27 Mars 2017 relative au devoir de vigilance des sociétés mères et des entreprises donneuses d’ordre’. For the analyses of the law see Elsa Savourey et al., ‘The French Law on the Duty of Vigilance: Theoretical and Practical Challenges since Its Adoption’, Business and Human Rights Journal, 6/1 (February 2021), 141–152.

38 See https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/19/305/1930505.pdf, accessed 22 June 2021, and also https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/06/11/germanynew-supply-chain-law-step-right-direction, accessed 22 June 2021.

39 See Edward McClelland, ‘The Rust Belt Was Turning Red Already. Donald Trump Just Pushed It Along’, The Washington Post (9 November 2016), https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2016/11/09/the-rust-belt-was-turning-red-already-donald-trumpjust-pushed-it-along (https://perma.cc/LES7-JNQ3).

40 See David Kucera et al., ‘Automation, Employment and Reshoring: Case Studies of the Apparel and Electronics Industries’, Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal, 41/1 (2019), 235–262.

41 Moul, ‘Reshoring: COVID-19’s Impact on the Supply Chain’.

42 Patrick Van den Bossche et al., ‘Global Pandemic Roils 2020 Reshoring Index, Shifting Focus from Reshoring to Right-shoring’.

43 See https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/BILLS-116s3780is, accessed 7 June 2021.

44 See https://hipa.hu/, accessed 22 June 2021.

45 See https://hipa.hu/, accessed 24 June 2021.

46 Patrick Van den Bossche et al., ‘Global Pandemic Roils 2020 Reshoring Index, Shifting Focus from Reshoring to Right-shoring’.