Viktor Orbán’s continuous governance since 2010 fits into the long-standing, centuries-old historical–political pattern of Hungarian history. All this is not independent of the socio-cultural trends that give each system its epochal validity.

The 33 years of Hungarian political history after the regime change are already suitable to be examined on a historical horizon, i.e. to be considered in itself, and also to be placed in the framework of modern Hungarian political history. This is confirmed by the unity of its phase beginning in 2010, which is again valid, not only in itself, but also in comparison to the developments of the last century and a half. To put it all in perspective, the System of National Cooperation is not a historical aberration, but a ‘relative’ of the long-term cycles in Hungarian political history.

Permanent Governance

Such an examination can begin by recognizing that, in Hungarian political history, cycles of longer duration are unfolding. Modern Hungarian politics, for example, began two hundred years ago with the initiatives of the reform era in 1825. The resulting domestic policy, which was, in the words of the great era, ‘self-sustaining’, prevailed for a hundred years (1848–1948), with minor interruptions, including half a century of constitutional life for the Hungarian half of the Austro–Hungarian Empire (1867–1918) and a quarter of a century for the independent Kingdom of Hungary (1920–1944).

These were the political–historical frameworks within which the larger and smaller historical–political cycles took place, interrupted by the various autocracies, occupations, and coups that followed. The great Hungarian revolutions of 1848 and 1956 were fought for constitutional freedom and therefore were followed by wars of independence, while the foreign occupations (the German invasion of 1944 and the Soviet one that immediately followed) were accompanied by coup d’états and totalitarian dictatorships, and can therefore be excluded from the historical period that now brings lessons for us.

Let’s now turn to the two periods, which are continuous in terms of their public law and political culture, and which meet the requirement of being the result of an organic, domestic historical development. One of these longer cycles, apart from the revolutionary–counter-revolutionary interlude from 1918 to 1920, lasted from the Austro–Hungarian Compromise to the German occupation, i.e. from 1867 to 1944. The first 50 years of this period were, in the words of Hungarian politician Gusztáv Gratz, the dualist era, while the last 25 were known as the Horthy era. Both periods are characterized by the thesis that great eras are associated with long periods of governance, with shorter periods before and after. These long administrations, lasting at least a decade,

not only constitute a system in and of themselves, but also define the complete epoch by which they were framed.

Again, to jump ahead a bit, we can assert that the Hungarian political system of the Franz Joseph era was established under the governance of Hungarian Prime Minister Kálmán Tisza, while the Horthy era was consolidated by Prime Minister Count István Bethlen.

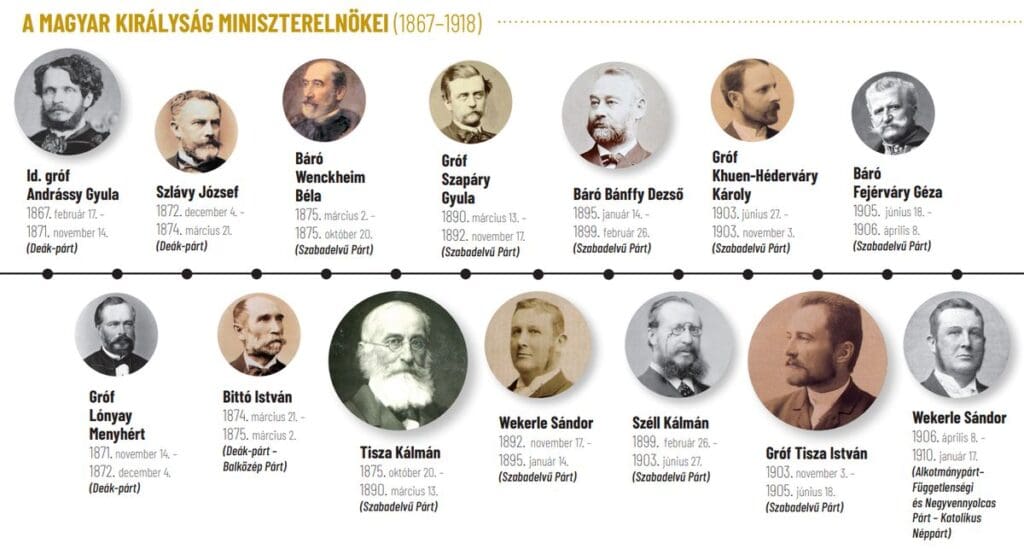

During the 50 years of dualism, our country was led by almost 20 prime ministers, 16 in number, since some of them occasionally returned to the executive (not counting János Hadik, who was appointed but never formed a government eventually), of whom Kálmán Tisza was the longest serving, from 20 October 1875 to 13 March 1890, i.e. for almost fourteen and a half years.

The contrast between the time in government of those who preceded him and those who succeeded him is sharp. Prior to his terms in office, a total of five heads of government served, of whom the first dualist prime minister, Count Gyula Andrássy, remained in office for four years (1867–71), while four others lasted only a half to a year and a half. Of the three heads of government who succeeded Tisza, two lasted only two and a half years, one more than four, followed by a quiet period, i.e. the turn-of-the-century reign of Kálmán Széll (1899–1903), which finally brought domestic political calm and stability. Then, in the last 15 years of dualism, from 1903 until the Aster Revolution, nine prime ministers followed each other, of whom Sándor Wekerle and István Tisza, the son of Kálmán Tisza, served non-consecutive terms. The former spent a total of half a decade in government, while the latter, after his first administration of more than a year and a half from late 1903 to mid-1905, spent a further four years in power, from mid-1913 to mid-1917.

It is worth adding that Kálmán Tisza alone had a government that spanned parliamentary terms, as he won five consecutive elections (1875, 1878, 1881, 1884, 1887), first with an 80-per-cent majority, the last time with a majority of more than 63 per cent, and winning an absolute majority in the House of Representatives three times. (However, the governing party, re-established by his son as the National Party of Work, fell 20 MPs short of a two-thirds majority in 1910.) Compare this with the fact that the 1872–75 crisis was a single parliamentary term, during which four prime ministers succeeded each other, and the legislative term after the 1910 election, which was extended by the First World War, saw five heads of government.

In the Horthy era, we had 11 prime ministers (not counting those after 19 March 1944), nine politicians in number, since Pál Teleki held the office twice.

István Bethlen was Prime Minister of Hungary from 14 April 1921 to 24 August 1931, i.e. for ten years, one month, and one week.

Prior to that, two people were running things at the same time, literally, as Sándor Simonyi-Semadam was prime minister only for a few months, and Pál Teleki quickly went down with the first coup as well. Bethlen was followed by seven others, but Gyula Gömbös was the only one to serve for a longer period, almost precisely four years (1932–36), while the others spent less time in government: two of them for roughly half that time (Kálmán Darányi, Teleki for the second time, and Miklós Kállay) and three for less than a year (Gyula Károlyi, Béla Imrédy, and László Bárdossy).

As far as parliamentary terms are concerned, Bethlen was the only one to win elections as head of government twice, in 1922 and 1926 (Gömbös once, in 1935), first by winning 57.4 per cent of the National Assembly seats for his party, which he increased to 64 per cent by joining with two smaller Christian factions; and then by winning almost 70 per cent of the seats alone, which he increased to no less than 83.5 per cent together with the Legitimists. Bethlen was also the only one to complete two full terms; in the 1920–22 legislative term, there were three prime ministers including him, two in the 1931–35 term, and four in the 1935–39 one, which was extended again because of the new world war.

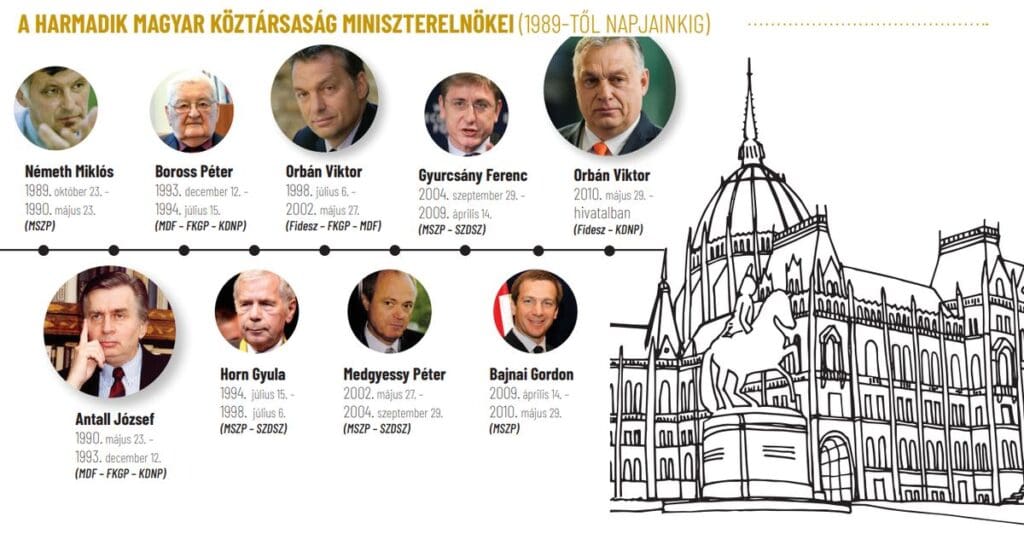

Since the regime change, we have had eight heads of government, of whom only Viktor Orbán has had more than one term. Three before Orbán’s first term in office, from 1998 to 2002, and three after that. Since then, he has been in power all along. Therefore, his time in government is made up of a civilian government he led from 6 July 1998 to 27 May 2002, and then four more terms starting from April–May 2010, all with two-thirds legislative mandates. With his current term running until spring 2026,

Orbán has every chance of becoming a historical record holder after 16 years in power.

It is also worth looking at the history of prime ministerial and parliamentary terms in this era. Apart from Gyula Horn and Viktor Orbán, the country has had no other prime minister to complete a whole term: József Antall was prevented from doing so by his unfortunate death, followed, for a little over half a year, by Péter Boross. Then, between 2002 and 2010, there were three Socialist prime ministers. Péter Medgyessy was removed by Ferenc Gyurcsány after just over two years in government so that he could complete the second half of his term. After winning the 2006 election in a unique way as an incumbent for the first time in the period after the regime change, Gyurcsány stayed in office for less than three years, as his coalition partner backed out in April 2008, and he then was replaced by Gordon Bajnai in April of the following year for the remaining more than a year of that term.

From System to a Whole Epoch

Since the 2018 elections, which ended in a third two-thirds legislative mandate again for the Fidesz–KDNP, we have been talking about the Orbán system, but after the fourth, even greater victory in 2022—in political terms at least—, it is certainly worth talking about a whole epoch.

Here, too, the study of Hungarian political history is of help, as we can note the same characteristics of Tisza and Bethlen in relation to the political leadership of each era. They are the following: it is a long-lasting, stable, strong, and united party that secures the parliamentary majority of the government, and it is led by a statesman with a charismatic character, who undertakes some great national task, and may carry an intellectual current that was already defined at the time—often expressed in architectural and cultural terms—and later on it certainly develops a common memory.

In the time of Kálmán Tisza, the national undertaking was the building of the modern Hungarian state; in the time of István Tisza, its preservation; and in the time of István Bethlen, its re-establishment.

Each long governance had its own dominant party: behind the Tisza cabinets, there were the Liberal Party and its successor, the National Party of Work, and in Bethlen’s case, the Unity Party, active from 1922 to 1932. But it is not incidental, as we shall see later, that the latter two were also served by intellectual newspapers, both with an acclaimed celebrity of the time: István Tisza founded the journal Magyar Figyelő (Hungarian Observer) in 1911 with Ferenc Herczeg, a conservative nationalist author, while István Bethlen launched the journal Magyar Szemle (Hungarian Review) in 1927, together with historian and publicist Gyula Szekfű (the latter two did not deny the continuous relationship between them).

It is typical that the head of state, first the apostolic Hungarian King and then the Austrian Emperor, Franz Joseph, then, in the kingless era marked by the figure of Miklós Horthy, the long-reigning head of government, first Kálmán Tisza, then István Bethlen, were followed by prime ministers who continued the governmental model for a certain period. It was for this reason that left-wing historiography coined the term ‘Tiszas’ Hungary’ after the son, who to some extent continued his father’s work, meaning the dualist system, while Bethlen was succeeded by another Catholic count, Gyula Károlyi, who was followed by the son of the Lutheran teacher from Murga, Gyula Gömbös, a general staff officer, as a kind of ‘regime change within an era’.

The system of epochal politicians is also continued by their successors in other countries: for example, António de Oliveira Salazar’s 36-year rule from 1932 to 1968 was extended by six years by his former deputy prime minister Marcello Caetano; Ronald Reagan’s two terms from 1980 to 1988 were followed by the administration of his vice-president George H.W. Bush; and Margaret Thatcher’s term from 1979 to 1990 was continued by conservative politician John Major, for a considerable period until 1997. That is why a decade and a half or two decades of conservatism can be talked about on both sides of the Atlantic.

As the Hungarian public discourse called them,

the ‘General’ (Kálmán Tisza), the ‘Iron Earl’ (István Tisza), and the ‘Smallholder’ (István Bethlen) all left their mark and are still remembered

(to avoid any misunderstanding, the ‘Old Man’ [János Kádár] cannot be included here, since the former were prime ministers of constitutional–parliamentary systems, while the latter, although he headed the Council of Ministers twice, derived his power from his position as Party Secretary General). Widely reputed Hungarian novelists and poets such as Kálmán Mikszáth, Endre Ady, Gyula Szekfű, and Dezső Szabó all epitomized an epoch, sometimes as leading statesmen, sometimes as evil spirits. But it is no coincidence either that their current opposition, which for generations failed to succeed because of their lack of talent, conflicts of interest, or narrow-mindedness, identified them with their voting bloc (‘mamelukes’) or with an act they considered blatant (voting with handkerchiefs) or simply accused them of corrupt concentration of power. It is still an ongoing pattern to this day.

Permanent Victory

In twelve years, the Fidesz–KDNP party alliance has won four two-thirds legislative mandates in a row, while winning three local municipal elections and two European Parliamentary elections. However, its success story has actually been ongoing since the autumn of 2006, when it won the municipal elections during the internal political crisis, the social referendum in the spring of 2008, and the EP elections the following summer. Since then, the Hungarian right has won a majority in every election.

Alongside political power, we cannot forget the power of culture, which is a superstructure that will forever reverberate back to the foundations. ‘The spirit must also be governed’—the first consistent drafter of this idea, Antonio Gramsci, in one of his booklets written in prison during the age of fascism, argued that lasting rule requires a ‘permanently organized consensus’, the creation and maintenance of which is not the task of the state but ‘of the private sphere’, as consensus is created freely.

He added: ‘The “everyday” practice of hegemony, which has become a classic in parliamentary systems, is characterized by a balanced combination of force and consensus.’ In another note in his booklets, written years later, it is said that ‘the history of subjugated social groups is necessarily fragmentary and episodic’, and that its curse ‘can only be broken by “continuous” victory, but not immediately’. These two seemingly disparate notes on the subject suggest, for today, that on the one hand, ‘permanent victory cannot be achieved by power alone’ (Tibor Szabó), and, on the other hand. that political stability and national consensus are equally important for the establishment of a lasting order. In short,

the cultural shadow of a long governance is even longer.

Click here to read the original article.

Related articles: