By the end of 2021, with the new German ‘traffic-light’ coalition agreement and the Warsaw Conservative Party meeting in early December 2021, the European political map has essentially been redrawn. The standing result is, on the one hand, a Berlin-centred, ideological (left-wing, new-left, progressive, liberal, and green) political camp and, on the other hand, a Warsaw-based, conservative, Christian Democratic, pragmatic political community.

It is important to see that the ideological political camp has little to do with what it calls itself: it is a ‘left’ that wants to free up competition for cheap migrant labour for the European working class; their ‘liberalism’ is characterized by prohibitions (sanctioned by anathema and excommunication) and compulsion to align; they say they are ‘green’ but they seek to address sustainability through a mere exchange of technology, without taking into account the ecological effects of the consumption-centred destruction of rural life, families, and communities.

In the classical senses of the terms, this political camp is not left-wing, liberal, or green, but utterly ideological in the sense that it wants to ‘engineer’ society. While ‘engineering’ society, it wants to impose the implementation of ‘engineering design’ by coercion—in other words by ‘soft’, i.e. psychological violence, by creating coercive situations, like, for example, rule of law conditionality.

The other political camp is still hesitating, still working out what to call itself. It has already saddled itself with the unhelpful term ‘illiberal’, though in fact it is much more tolerant and freedom-oriented than the ‘liberals’. This political camp has also called itself Christian, though the closest thing it had to do with religious doctrine was that it wanted to prevent Christians from being persecuted for their faith and values. Furthermore, it has already called itself conservative, despite the fact that it does not want to preserve the current bad state of Europe, but rather wants to see a change: definite solutions to serious problems.

The common denominator is the will to prevent the crisis and to preserve and maintain the stability, the natural integrity, and ultimately the existence of human individuals, families, nations, states, and the world order itself

So what is the common denominator of this political camp? My answer is: the concern that Europe and the world will collapse, will end up in a crisis on the path that the ideological camp wants us to take. Nations (may) end up in crisis, states (may) end up in crisis, and the world order (may) end up in crisis, just as people’s individual lives and families are already in crisis. The common denominator is the will to prevent the crisis and to preserve and maintain the stability, the natural integrity, and ultimately the existence of human individuals, families, nations, states, and the world order itself. Basically, sustainability is the common denominator of this camp … and let us not to forget that this should not be ideological but rather pragmatic sustainability. The interesting thing about the new European political map is that sustainability is a central issue for both camps. For the ‘Berliners’, sustainability is an ideology, but for the ‘Warsawians’, sustainability is a practical, pragmatic task to solve, and one that is severely hampered by an (overly) ideological approach to these issues.

To sum up, there are the so-called ideological ‘leftists’ who are in power in much of Europe, including Berlin and Paris, and there are the pragmatic ‘rightists’ who are in power in the Visegrád Group countries, especially in Budapest and Warsaw, but, for the time being, they are in opposition to most of Europe.

The debate is essentially between these two political camps. However, let us note that in addition to the debate, there are also common denominators among them. One definite common denominator, for example, is that both political camps want sustainability, even if they have different views on how to realize it. At the same time, both political camps want to make Europe strong and competitive again in the world, even if they differ regarding the means to achieve these aims.

In the light of these common denominators, it can be observed with satisfaction that the new German chancellor, Olaf Scholz, sent a message to Poland and to every Central European government after the signing of the German coalition agreement, underlining that he wanted to have good relations with these countries. It is possible—but by no means certain—that a civilized and constructive, though tough and consistent, debate will develop between the two political camps. This is one of the main challenges for Europe in the coming months.

The main loser in this new political situation is the European People’s Party, which is virtually nowhere on the map: it is barely in power anywhere in Europe, and has essentially nothing to say in the so-called ‘great European debate’ about the future of Europe. I think we can conclude that an alternative to the ideological new left is now the pragmatic new right.

You may or may not like the new political map, but—without doubt—it has one advantage: those who support the direction that Europe is currently heading as well as those who do not support it now have political representation. We can say that there are real alternatives in European politics. European citizens have a choice about what they prefer, represent, and support. This situation used to be called democracy. The good news is that European democracy may be strengthened thanks to the developments of recent months. Today, Europe is more democratic than it was before the Warsaw Summit, and we Hungarians will do everything we can to ensure that the next elections in the member states and in the European Parliament further strengthen democracy in Europe on the basis of real alternatives. It should be added that this is not only about Europe, but also about the greatest common homeland of humanity, the created world. Globally, the European pragmatic political camp also constitutes a potential alternative to internationalist ideologies.

The world order, established in 1945, the alpha and omega of which is the UN Charter, is value-based. Its core values are peace, the sovereign equality of states, human rights, and the global public good.

The new leftist internationalism seeks to suppress the sovereign equality of states from among these values. It wants to transfer most of the powers of sovereign states to international organizations and other global actors which have no democratic legitimacy. In other words, it wishes to create a world government, while transferring competencies to non-governmental organizations without democratic legitimacy. One thing is a clear priority for them: to make states and nations as weak as possible.

If we look at the pragmatic right—and not just in Europe, but in the US, and the Japanese, Indian, Brazilian, and other forms of right-wing thought—we arrive at the conclusion that they approach the issue from a precisely opposite point of view: they strive to strengthen nation states. They intend to build global international cooperation that strengthens the ability of states to ensure the security, freedom, and prosperity of their citizens. In this sense, the pragmatic political camp is genuinely conservative. It does not want to overthrow the world order and does not aim to abolish or replace the values of the UN world order.

I am of the opinion that the political slogans of the pragmatic new right have not yet been elaborated, but it is time to start brainstorming. It could be, for example: ‘sustainability— but wisely’ or ‘the world can be better without a world revolution’… So Europe and the world are heading in the wrong direction and need to be turned in the right direction. What are the most important issues the new right needs to tackle?

The Wrong Direction

We are going in the wrong direction because there are opposing ideologies that try to violate or abuse ‘reality’. They approach reality ideologically, and in so doing they limit economic policy, gender and family relations, but also the relationship between the great powers, religious issues, migration, and especially sustainability, which is reduced to purely environmental and labour market issues, thus making some countries’ energy policies unsustainable.

The latter does not affect Hungary so much because Hungary’s energy policies meet ideological expectations, but those of Poland, for instance, do not, and if Poland’s energy security is shattered, one of Europe’s bulwarks will be shattered. The ideologists talk about sustainability, while it is Western civilization and the world that are becoming unsustainable.

Old and New Kind of Left-Wing Ideological Pressure

There are two kinds of left-wing ideological pressure on the world: one is the self-described communist ideology and the other is a left-wing ideology that calls itself ‘liberal’. However, ‘liberals’ are no longer liberal since liberalism today is all about prohibition. A couple of years ago a Hungarian woman living in America received from her friend a list of words that are not recommended to be uttered in front of African Americans. The list included, for instance, the word ‘hair’. She sent the list out of benevolence because she wanted to protect her Hungarian friend. This is what famous American liberalism looked like several years ago—now, with the outbreak of identity politics, it has become worse. Liberalism is no longer liberal. It is not tolerant; it just usurps the name. The left-wing ideology calling itself ‘liberal-progressive’ is beginning to destroy traditional camps and language, including that of liberalism.

‘Liberals’ are no longer liberal since liberalism today is all about prohibition.

The Good Direction

The essence of a good world is a sustainable world. These issues need to be approached in a pragmatic way. The right direction is the opposite of what we said before: people live on work, not on welfare. Work means creating value, and society is above all reproduced on the basis of family reproduction. The left-liberals are conducting a human experiment: they want to reproduce in laboratories or even by experimental sexes. Where is the fault line between these two? It is between a sustainable and an unsustainable world—which divides societies in both Europe and America.

Under President Trump, it became clear that his camp was dominated by sustainability advocates. The ideologies of the left should not be opposed by a conservative or Christian Democrat counter-ideology, but by intelligent pragmatism. And this intelligent pragmatism might be the common denominator of the new right.

Shaded of Difference in the Common Camp: State Intervention

Within the camp, there are nuanced differences in the way we define ourselves as conservatives, or Christian Democrats. These are political identity-defining definitions. The nuanced difference is that the Christian Democrats allow some state intervention, as opposed to conservatives, but this difference should not be exaggerated. Because, on the one hand, the emerging new Christian Democratic camp (e.g. Fidesz in Hungary) also shares the position that one should not live on welfare, but that a work-based society—or workfare society, as we name it—should be established, and that free trade should be the engine of the economy.

On the other hand, traditionally, Christian Democrats have undoubtedly been more permissive of state intervention. However, only in critical cases should the state intervene, which is similar to the view of the British Conservatives: industries or services that are strategic in terms of security policy are temporarily supported by the state in times of strategic challenge. See, for instance, the British levelling up of historical heavy industry zones.

China and Russia

In the case of China and Russia, goals and means should not be confused. The goal is our policy: the goal of new right politics is not to cross the Xi or Putin regimes, but to achieve our own goals, both in our own circles and in the world. The Chinese and the Russians should not stand in the way of this, and it is no problem if they help, for instance, in combating climate change and terrorism.

If we want Russia and China to adopt a fair approach to free trade, or rule-based global trade, the question is to what extent this can be facilitated by sanctions and to what extent by cooperation. Obviously, every country’s experience differs depending on its size and situation, but ultimately we have a common goal. Europe as a whole is increasingly following this line, and almost all countries employ a mixture of cooperation and sanctions. The only difference concerns the proportion of these means. The EU will have to come to an agreement on this matter as soon as possible.

Values of the United Nations

Above all, everyone should be loyal to the UN Charter—which is, in fact, a ‘world constitution’.

This list of values also roughly implies an order of priorities: in the interests of peace and security—but only in the interests of peace and security—the powers of the permanent members of the Security Council are placed above sovereign equality in terms of their competences. So peace and security are even stronger than sovereign equality.

However, in the interests of human rights and the global common good, the Charter allows very little interference in the internal affairs of states, even by the UN itself, so sovereign equality is at least as fundamental as human rights and the common good.

For a UN, values-based world order, what is important is that the world of US–China antagonism (possibly with some Russian input) should not override the UN values of peace, security, the global common good, and sovereign equality. The US–China relationship, especially since Biden, is by no means exclusively adversarial: see the Alaska Summit earlier this year, which started with a big public hissy fit, then continued behind closed doors, and ended with an unknown outcome, but with both sides leaving relatively satisfied.

Loyalty among NATO Allies

If America can allow itself to try to cooperate with China for its own sake and for the sake of the world, why should not a country of ten million people? So allies must be loyal to one another in a way that is also loyal to the Charter, and within that to sovereign equality. This does not preclude them from cooperating or even arguing about, for example, human rights or geopolitical issues, but it does preclude them from educating or coercing one another on such issues.

On geopolitical issues, NATO allies have a very well-defined procedure for how their loyalty to one another and to the alliance works: this is defined in NATO documents based on the Washington Treaty (which is also based on the UN Charter). We should not forget the new Strategic Concept under elaboration, which will define threats, deterrence, dialogue, rivals and partners. Of course, cooperation can and should go beyond what is defined in NATO documents, but this should not be demanded of one another. Rather, it should be initiated on the basis of mutual, shared interests and values, and above all respect.

Russia on its Own

When it comes to Putin, the question is always, what would happen if Putin was not there anymore? Unfortunately, my answer is that then there would be anarchy in the space between China and Europe, because that is what in fact began to unfold in the 1990s, and Putin—whether we like his methods or not—has stabilized the country.

We must prevent the use of these methods in our countries, but the question must also be asked as to what the West has to offer either to the Putin regime or to Russian society. The problem is that there is no real and actual counter-offer—a strategic vision of how stability can be ensured in other ways. Therefore, the offers of the West rarely give an alternative to current Russian geopolitics, but compromise with it—this is what is especially dangerous for the countries that Russia considers to be part of its sphere of interest, and dangerous for my region, Central Europe.

Russia has two paths to Europe: a manipulative one (i.e. direct influence in the countries of Europe, including Western Europe, through hybrid means: propaganda, intelligence, etc.) and a geographical one (in areas closer to it, where it can still rely on the legacy of the Soviet occupation, gaining influence and influencing European decision-making through the countries it ruled for decades).

From the latter (geographical) point of view, the more unstable the Central European countries are, the more dangerous Russia’s policy of influence becomes, i.e. the less effective they become in exercising their sovereignty.

Therefore, it is worth doing what Viktor Orbán used to say: ‘watch my hands’—if pragmatic cooperation with Russia offers the possibility of stability (and in the case of Hungary, this is undoubtedly true), then—paradoxically—pragmatic cooperation with Russia is the best defence against Russian geopolitical ambitions.

Post-Brexit Tripartism of the West

After Brexit, the West has become tripartite. Therefore, the effectiveness of the West depends on the quality of relations between the three poles. And high-quality policy takes place when there are parties in government which respect national interests, sustainability, and traditions. When there are pragmatic governments, it is good politics—when politics is not dominated by ideology, when the ruling policy works for the benefit of the people in a practical way. So on the one hand, there should be smart policies.

The power of the West comes from two sources. One source is the quality of decision-making in the three poles that make up the West. And from this point of view, the quality of European politics is important. In other words, decisions must be taken in the spirit of intelligent pragmatism because then the world will be sustainable.

The most important thing is to respect the interests of all parties within the treaties

As long as the West was dichotomous, one trade treaty could ensure the coherence of the West: TTIP. A good trade agreement! But we failed. Now three trade agreements, which are currently under preparation, can do the same: EU–British, EU–US, and US–EU. It is in the interest of the whole world (i.e. in the interest of the people) to succeed. Plus, the most important thing is to respect the interests of all parties within the treaties. Then the parties will be interested in maintaining it. Changing the world for the better is our job—I see this as one of the most important next steps to take.

On the other hand, the quality of our cooperation matters. Political forces should have a common political vision for trade policy agreements between the three parties. The West, then, will not be cohesive or divided because it is organized into two or three large units, but because the relationships between these units are well regulated and well managed, or because they are not.

Brexit offered—perhaps still offers, but unfortunately this is a diminishing hope—the possibility of concluding treaties between the three parties that would strengthen each party and thus strengthen the West. We hope this chance does not fade away in 2022.

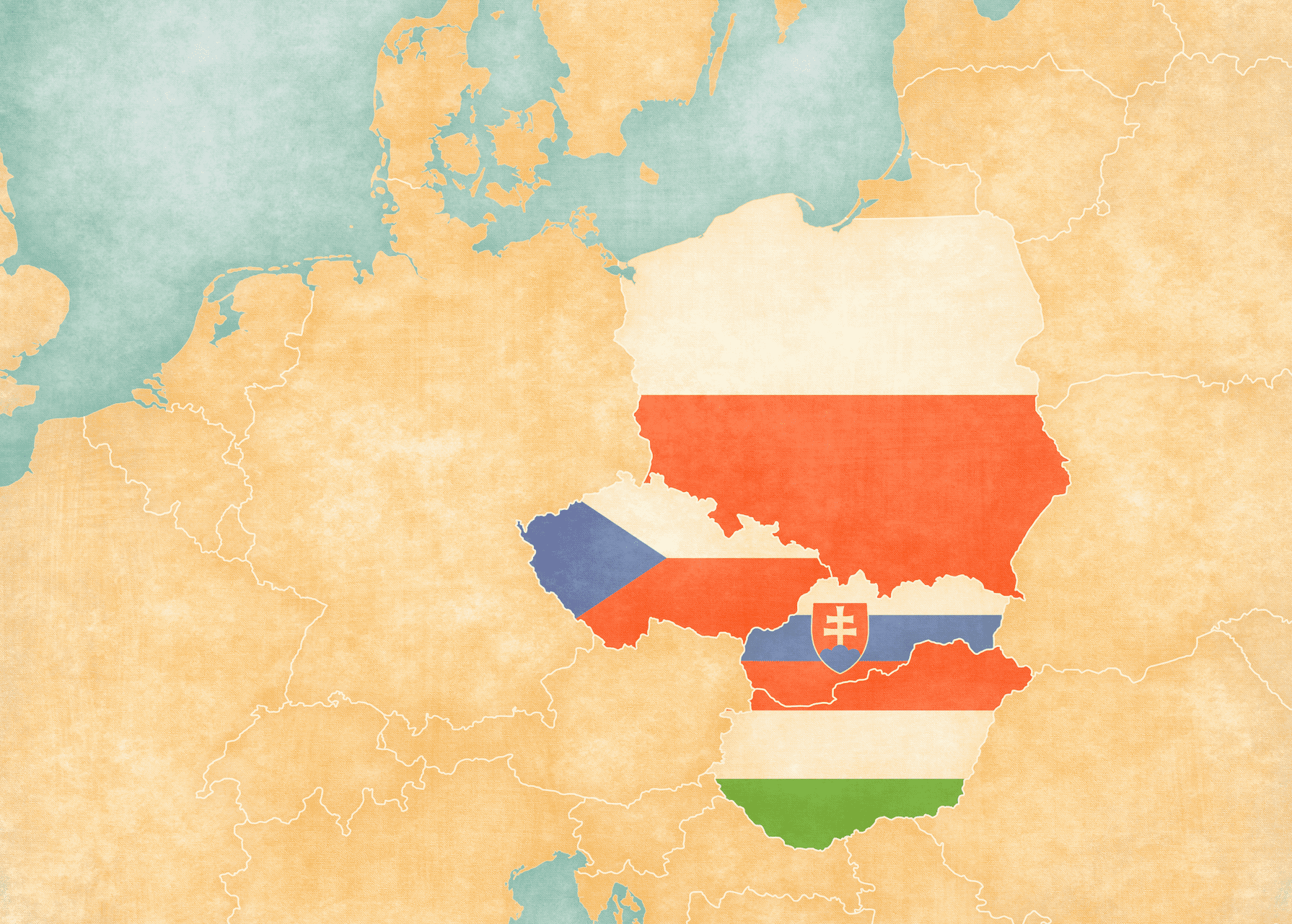

Visegrád and the Rest of the West

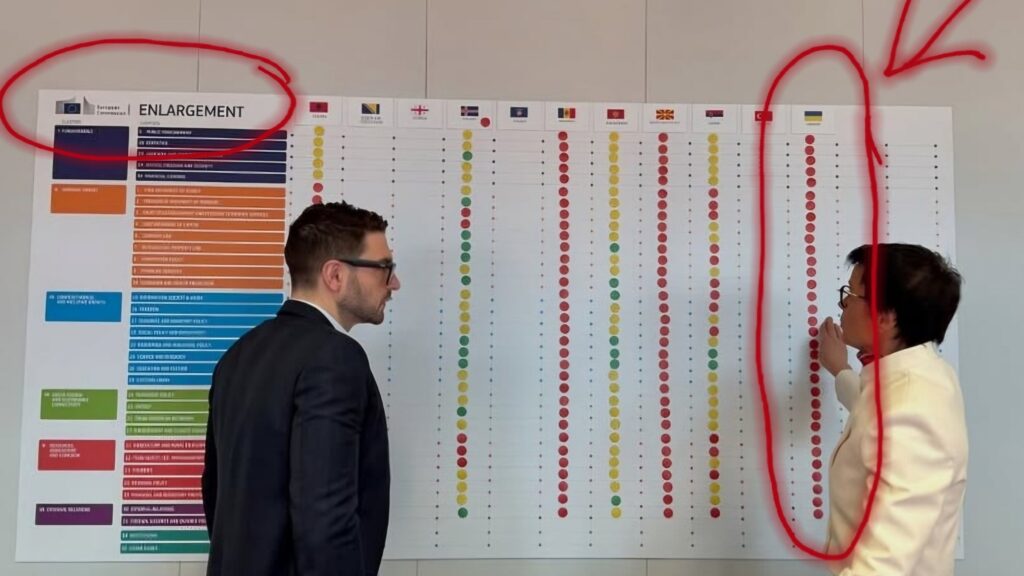

The V4, the thirty-year cooperation between four former communist, now NATO–EU member states, has received significant recognition lately. Originally their target was to speed up their own Euro-Atlantic integration, which they achieved successfully together. After joining these organizations, they decided to unite and lobby on certain crucial common interests in the EU. This ongoing target includes special attention paid to the enlargement and neighbourhood policy of the EU. Parallel to this, they have started to focus on creating a common regional economic space for trade, investments, and infrastructural interconnectivity, especially transport, energy, and digital nets.

However, the prominence of the Visegrád Group today stems from an entirely different source. Namely their common Visegrád mentality, a history-determined suspicion against assertive ideologies, and their deeply rooted intelligent pragmatism, which has helped them to develop political stability and relative prosperity in their countries in the past thirty years.

The fundamental transformation of the European political landscape including the collapse of traditional parties, especially the European People’s Party, has incentivized European political players to search for new approaches and partners. The Visegrád Group has thus become a magnet for various likeminded European efforts. It has facilitated dialogue between the new right parties with a strong focus on V4 and other Central European players. It is crucial that this dialogue should not be limited to party structures and the upcoming 2024 European elections, but should focus on important international and policy issues. If they followed the latter course, the Visegrád Group could provide a valuable service for Europe, the West, and beyond.