This article was published in Vol. 4 No. 3 of our print edition.

There is an appointed time for everything,

Ecclesiastes 3:1–8

and a time for every affair under the heavens.

A time to give birth, and a time to die;

a time to plant, and a time to uproot the plant.

A time to kill, and a time to heal;

a time to tear down, and a time to build.

A time to weep, and a time to laugh;

a time to mourn, and a time to dance.

A time to scatter stones, and a time to gather them;

a time to embrace, and a time to be far from embraces.

A time to seek, and a time to lose;

a time to keep, and a time to cast away.

A time to rend, and a time to sew;

a time to be silent, and a time to speak.

A time to love, and a time to hate;

a time of war, and a time of peace.

This study focuses on questions related to the Russia–Ukraine War, one of the most dramatic events in contemporary European history. It seeks to examine the extent to which the citizens of Europe feel that the official positions of Brussels (the EU) and NATO, and the resultant decisions, are their own. Using the following questions, posed as part of a Századvég Foundation survey conducted in thirty European countries, and the answers given to them, we seek to understand whether the people of Europe are pro-war or pro-peace.

1. Would you agree or disagree with your country sending weapons to Ukraine?

This is one of the most relevant questions and has been the subject of European and EU public discourse since February 2022. Nearly 200 billion dollars has been invested in Ukraine by the Democratic administration of the United States, alongside other financial and military aid from the West, including the EU. Arms shipments at the EU and NATO levels uphold Ukraine’s ability to confront the Russian Army and broadly hold the front.

In this regard, with the exception of the consistent Hungarian position rejecting arms deliveries, there is almost complete consensus among the political and military leadership of NATO and the political leadership of the EU.

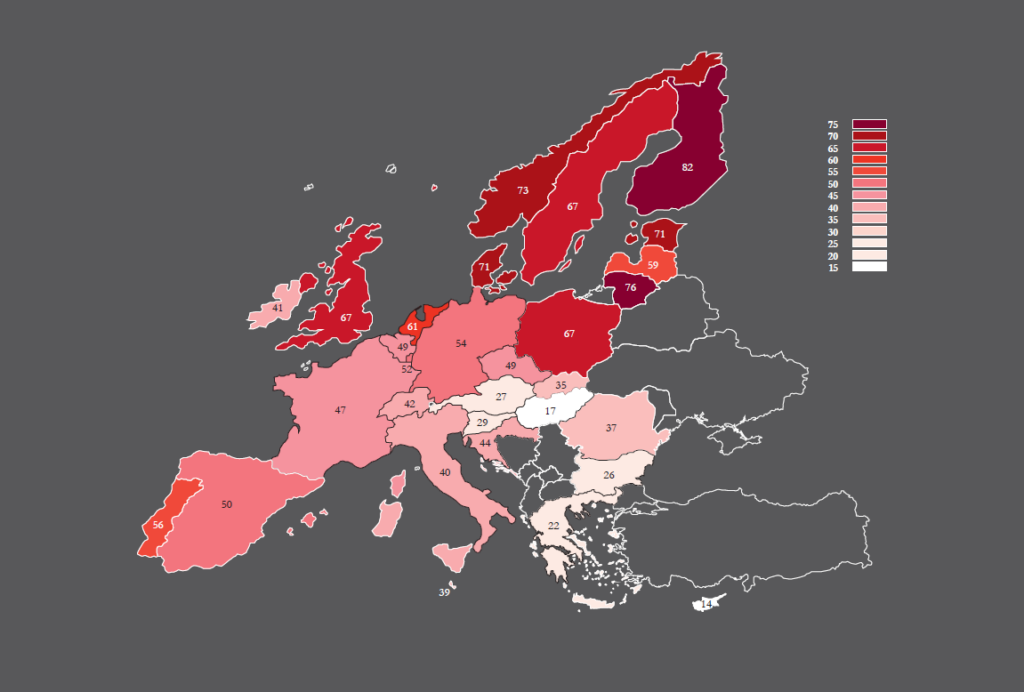

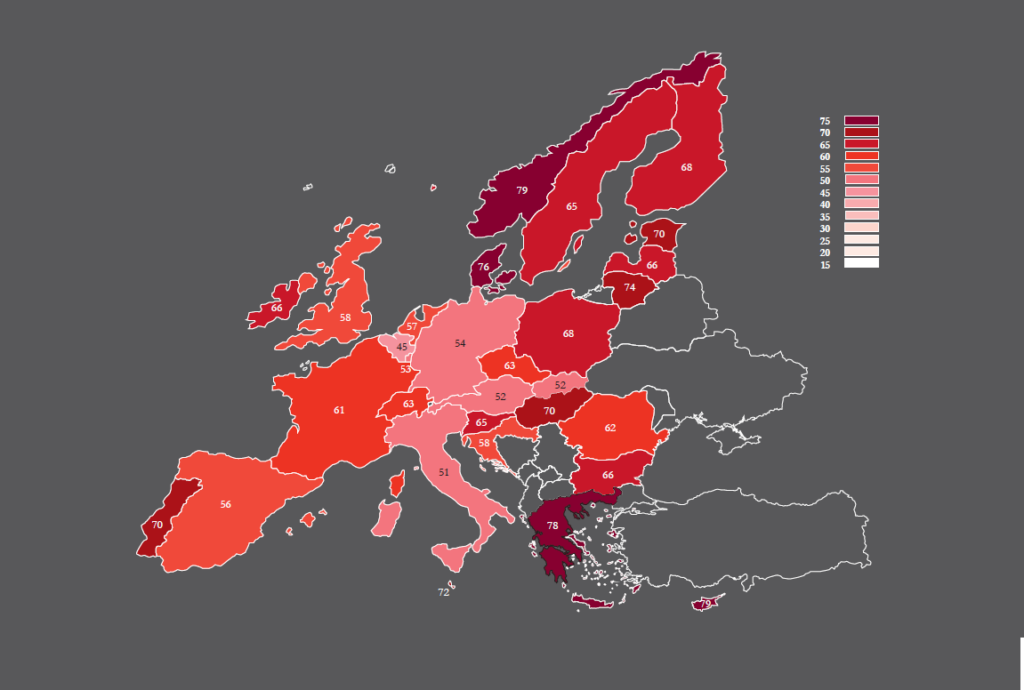

However, the survey shows that the pro-war attitude of NATO and EU political decision-makers does not enjoy the full support of ordinary people among the 30 countries surveyed by Project Europe 2024. In the Baltic states, Scandinavia, Poland, and the UK, the majority of respondents (over 50 per cent) agree that their country should send weapons to Ukraine. In almost half (14) of the 30 countries, more than 50 per cent of respondents approve of sending weapons. There are three countries (Belgium, the Czech Republic, and France) where the supporters and opponents of weapons shipments are essentially in equilibrium. In 13 countries, however, there are more opponents. In Croatia, Switzerland, Ireland, Italy, Malta, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Austria, Bulgaria, Greece, Hungary, and Cyprus, the majority of the population rejects arms transfers, and in the latter seven countries, the rejection rate exceeds two thirds. In Hungary and Cyprus more than 80 per cent are opposed to such transfers.

2. Would you agree or disagree with your country sending soldiers to Ukraine?

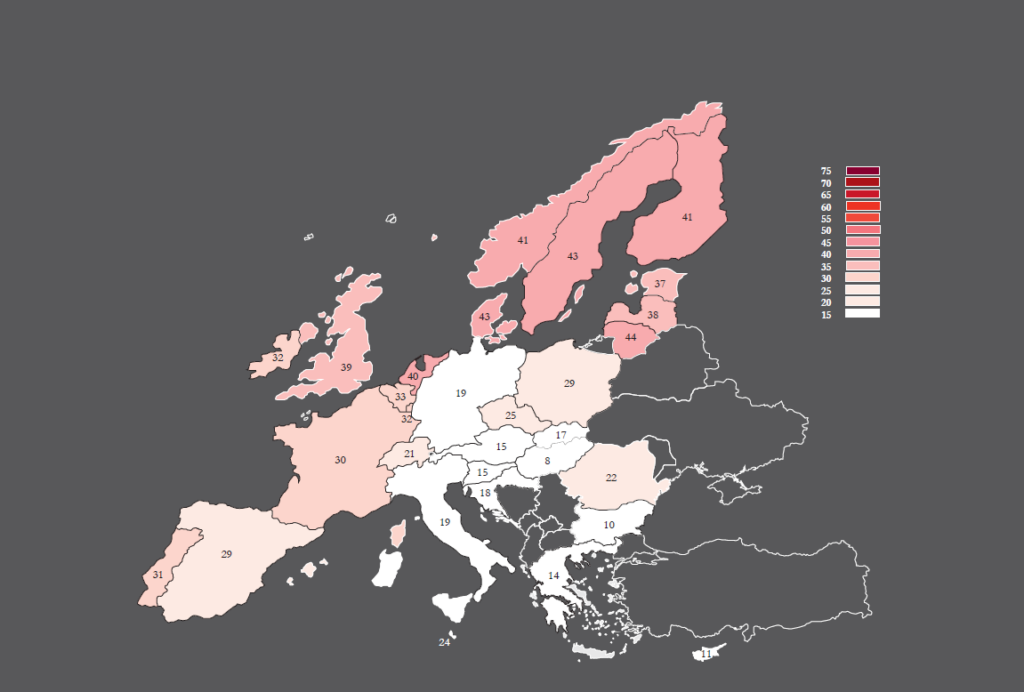

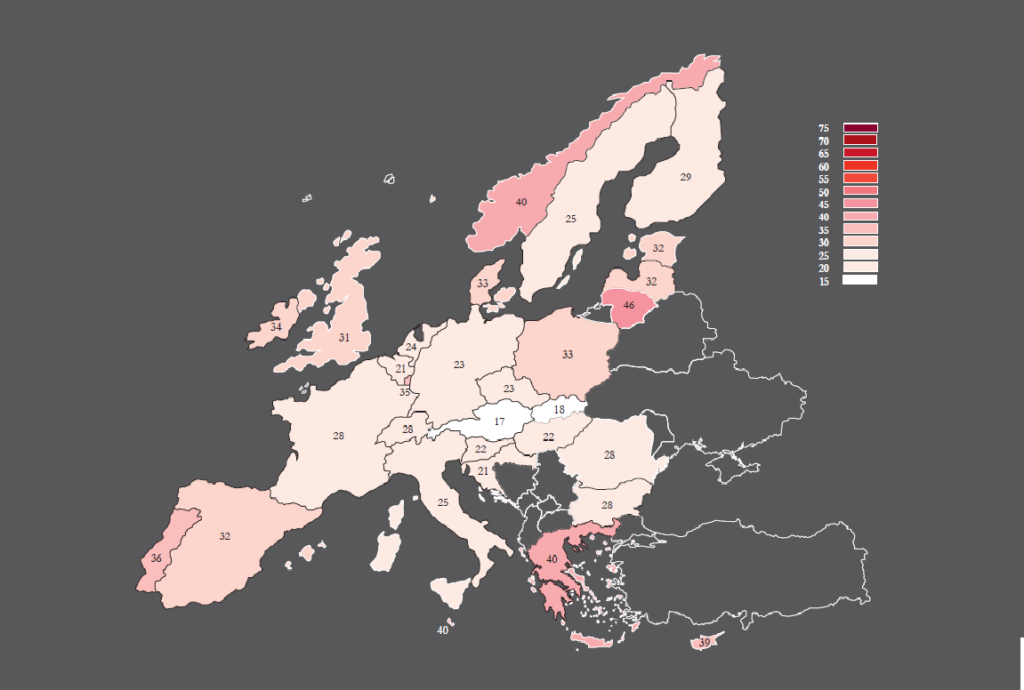

If people are asked whether they would send not only weapons but also soldiers to Ukraine, the balanced picture formed in the case of sending weapons changes completely: there is not a single country among the 30 surveyed in which a majority of respondents would support sending troops. Even in the Baltic and Scandinavian countries, which have the most ‘militant’ positions, the majority of respondents do not support their country sending soldiers to Ukraine (with only an average of 37–44 per cent backing the proposal).

It is interesting that even in Poland, which promotes and represents a staunchly anti-Russian position, only 25 per cent of respondents support sending soldiers to Ukraine, while 64 per cent, almost two thirds, reject it. In 19 of the 30 countries examined, two thirds or more rejected sending troops, and in 12 it was rejected by three quarters (around 75 per cent or more). At 91 per cent, the proportion who reject the proposal is highest in Hungary. Overall, 67/69 per cent of citizens in EU and EU+ countries reject the proposal, meaning that two thirds of European citizens reject the EU or NATO leadership sending troops to Ukraine against their will.

3. Do you support your country sending soldiers to another EU member state?

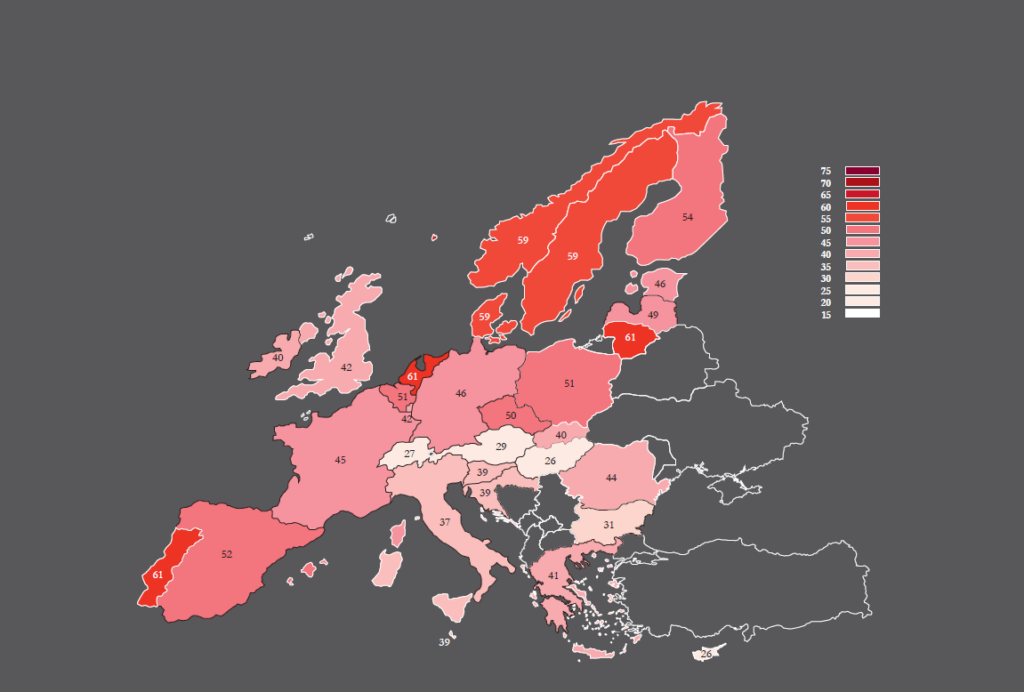

From the following question, it is clear that while the population of the 30 European countries examined categorically rejects sending troops to Ukraine (by two thirds), they are somewhat more open to sending troops to other EU countries. The majority of respondents from 12 countries stated that they would support their country sending soldiers to another EU country. This corresponds to the basic principles of NATO: member states must protect each other in the event of an external threat. In two countries (Estonia and France) supporters and opponents of the proposal were evenly balanced (at 46 per cent). However, in 16 countries, even this ‘friendly’ troop transfer was rejected by the majority. In Hungary, a large majority (73 per cent) rejected even this proposal.

4. Would you fight for your country?

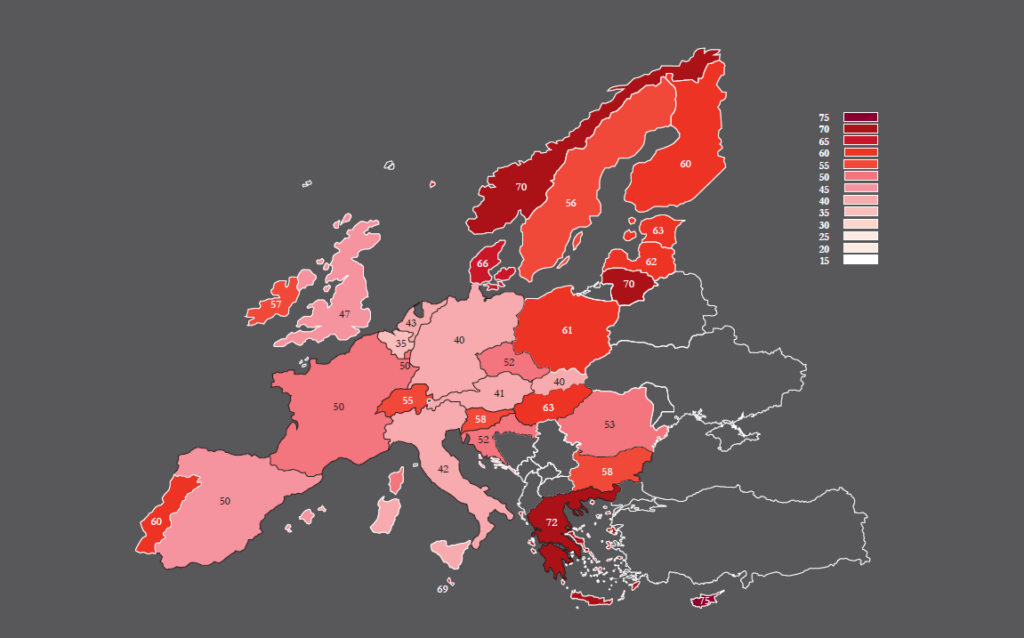

Századvég posed the same question a year earlier, in 2023, and with an even broader scope, to the citizens of 37 European countries. The picture at that time was quite discouraging, with majorities of citizens in only a few countries (mainly in the Balkans, Hungary, Poland, the Baltics, and Scandinavia) responding that yes, they would fight for their country. In the rest of Europe (Western Europe), the vast majority of respondents were unenthusiastic when asked if they would fight for their country. One may wonder about the degree to which Western immigrant communities consider the country where they live to be their homeland and—because this is what is ultimately at stake in this question and the responses to it—whether they would sacrifice their lives for their new homeland.

This picture has changed somewhat in the past year, perhaps as a result of the war rhetoric and psychosis promoted by the mainstream Western media. Enthusiasm for defending the homeland is still highest in the Balkans, East Central Europe, the Baltics, and Scandinavia, but in seven Western European countries (Spain, the United Kingdom, Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, and Belgium) and one East Central European country, Slovakia, fewer than half of the respondents answered in the affirmative. Indeed, in Germany, Austria, and Belgium, a relative minority of respondents said that they would fight for their country, and more answered that they would not. Hungary is tied for seventh place with 63 per cent of responses being affirmative.

In addition to the presumed reluctance of communities of an immigrant background, it is worth asking whether globalist ideological currents, such as the Open Society, have emptied the concept of homeland of meaning so that the majority of people no longer consider it a value for which they would fight, still less sacrifice their lives, since you can find a place to live in any country of the globalist Western world, not only in your native country.

5. Would you fight for your country on the territory of your own country?

Our wavering faith in citizens’ patriotism may be reaffirmed by the question of whether they would fight for their country on the territory of their own country. Here, the majority of respondents from all 30 surveyed countries answered yes. Here, the only question is the scale of the majority that would be willing to fight for their country on the territory of their own country. The percentage of those answering in the affirmative exceeded 70 per cent in nine countries (including Hungary).

6. Would you fight for your country beyond the borders of your own country?

If we continue this line of thought and ask whether citizens would fight for their country beyond the borders of their own country, responses once again resemble those given in answer to question four (would you fight for your country) and we see that there is nowhere where the proportion of positive responses approaches 50 per cent. In only two countries out of the 30 did a relative majority give a positive response: Lithuania (46 per cent) and Norway (40 per cent). In all other countries there were far more negative than positive responses, and the net result across 30 European countries was 28/27 per cent answering that they would fight and 54 per cent declaring that they would not.

In reviewing the responses given to this survey, it is clear that the greatest enthusiasm (if we can talk about enthusiasm in any of these sections) concerns the transfer of arms, which is somewhat removed from the life of ordinary citizens, and does not directly threaten their existence. As long as it is Ukrainians who are dying, a significant proportion of people in the West can accept this.

However, as soon as issues are raised that may personally affect the citizens of the country in question, enthusiasm drops significantly, and it becomes clear that very few people want to make personal sacrifices or become personally involved in the war. It is clear from the data that mainstream Brussels and NATO policy does not align with the views of their citizens. In contrast to the pro-war elite, the vast majority of Europeans are therefore pro-peace.

As Carl von Clausewitz put it in his major work On War (1993), in fact, war is the continuation of politics by other means. Have we run out of political tools?

Methodology

Since 2016, the Századvég Foundation has been conducting public opinion surveys covering the 28 member states of the EU, with the aim of examining the opinions of European citizens on the issues that most closely pertain to the future of the Union. Using a unique approach, the Project28 public opinion survey polled 1,000 randomly selected adults in each country, i.e. a total of 28,000 people, in its broadest survey to date. Among the most important goals of the investigation was to explore societal perceptions of the economy, and to map popular attitudes towards the performance of the European Union, the migration crisis, and the growing threat of terrorism. Following surveys in 2017, 2018, and 2019, the Századvég Foundation, on behalf of the Hungarian government, has been pursuing its studies under the name of Project Europe since 2020, with a continued focus on the most defining topics of European political and social discourse, such as the coronavirus pandemic, the energy crisis, and the Russia–Ukraine War. Data collection in 2023 and 2024 included the United Kingdom, Norway, and Switzerland, in addition to the member states of the European Union, meaning that the opinions of a total of 30,000 randomly selected adults were assessed using the CATI (computer-assisted telephone interviewing) method, between 26 April and 22 June 2023 and 14 February and 15 April 2024, respectively.

Translated by Thomas Sneddon

Related articles: