Bestaanszekerheid—i.e., livelihood security. That is the word that dominates the Netherlands today, and that is what the autumn campaign was all about. Because in the Netherlands, as in most countries in the Western world, the welfare state security of previous decades has been shaken by the Coronavirus pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and the subsequent energy crisis. The cost of living has risen, energy prices have soared to extreme levels, and increasing immigration and thus urban saturation, poor housing, and, in some areas, deteriorating public safety are also negatively affecting the daily lives of masses of Dutch people.

Getting into the Legislature is Extremely Easy, but Forming a Majority Government is Difficult

This upheaval has led to a political realignment implemented in last Wednesday’s parliamentary elections. The election was held after the government of Mark Rutte, the right-wing Liberal Prime Minister who has led the country since 2010, resigned in July after failing to reach a deal on the migration policy issue and the family reunification of refugees coming from war zones. A few days later, the PM announced that he would not stand for re-election and would leave politics. Still, Mark Rutte was the longest-serving prime minister in Dutch history.

With Rutte’s departure, therefore, a new chapter in Dutch politics began, and the field is now open for new contenders as well. This is also promoted by an electoral system that is as proportional as any in the world: in a purely list voting, 150 seats are up for grabs, and whoever reaches one hundred and fifty-fifth of the total vote, that is, 0.67 per cent, can send a member to parliament.

Thus, getting into the legislature is extremely easy, but forming a majority government is difficult. This is helped by the centuries-old Dutch democratic tradition, which is based on a combination of pillars (Reformed and Catholic, then left, right, and liberal), as well as a culture of compromise. Well, it is the latter that Rutte failed to create this summer on a sharp political issue, which led to the disintegration of his government.

Before the election, opinion polls showed an even race, with four political forces predicted to win between 20 and 30 per cent of votes. The first one was the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), led by Rutte, the second one was the right-wing populist veteran Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom (PVV), and the third one was the flagship of the left-liberal camp, the coalition of the Labour Party and the Greens (GL–PvdA), led into battle by another well-known veteran, Frans Timmermans. The fourth force is a new political movement, the Christian-social-centrist New Social Contract (NSC), led by Pieter Omtzigt.

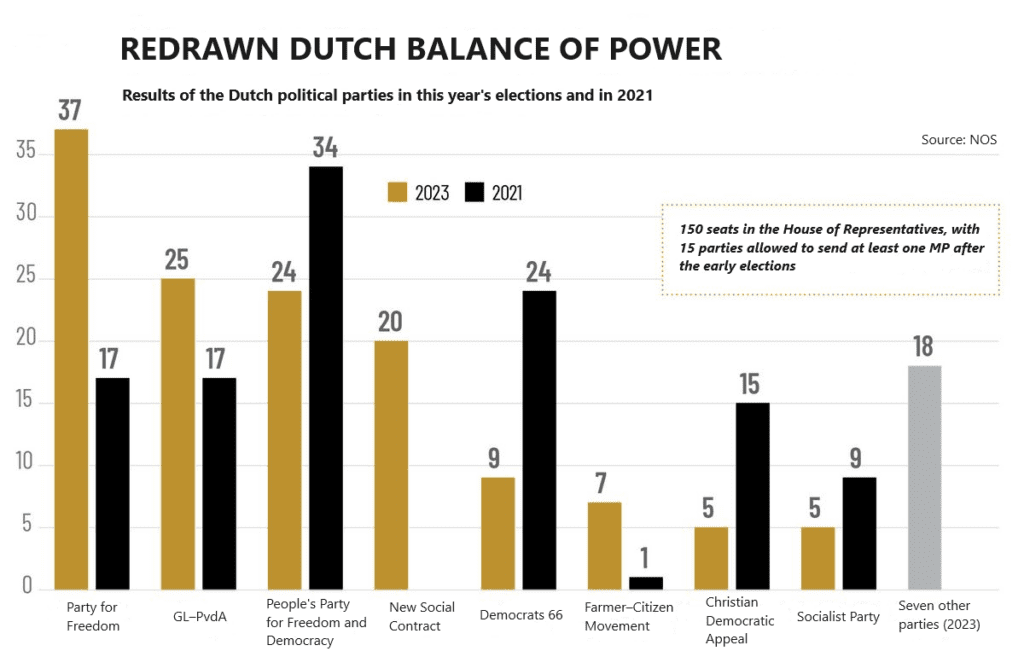

Instead of a battle of evenly matched forces in the polls, however, the result was a surprise: the Party for Freedom came in first, by far the most popular. Wilders and his party won 23.7 per cent of the votes, giving him 37 MPs, while the three main competitors had significantly lower results. Timmermans’ new left-liberal coalition won 15.6 per cent of the votes, the VVD 15.2 per cent, and the New Social Contract only 12.9 per cent. Besides them, eleven other small parties are sending one or a few MEPs to parliament, including the farmers’ party, the radical Calvinists, the formation representing immigrants, and Thierry Baudet’s weakened right-wing Forum for Democracy (FvD), which had previously announced itself as a challenger to Wilders, but the old campaigner finally beat them back and regained support from the more radical crowd.

But what messages, and what agenda did Geert Wilders win with? Well, not entirely novel ones, as the party leader is a veteran of Dutch politics: he has been in parliament since 1998, where he has criticized immigration and the social and political changes it has brought, once considered extremist, now increasingly popular and an election winner. Incidentally, he is also a colourful personality, and not just because of his hair, which has been spectacularly bleached for decades. His father is Dutch, and his mother part Indonesian—his ancestors lived in the remote crown jewel of the old Dutch colonial empire.

His wife, Krisztina Márfai, is a Hungarian-born former diplomat.

Thus, the Wilders family is a frequent visitor to the Hungarian countryside, to the home village of Geert’s wife, Nyírparasznya.

But let’s turn from Nyírparasznya back to Dutch domestic politics: Wilders’ big success has been in reiterating his old agenda, strongly criticizing immigration, Islamism, even Islam, and the overreach of the European Union. He began his political career in the VVD, working as a copywriter for the party before becoming secretary to party President Frits Bolkestein. Bolkestein later became European Commissioner, while Wilders moved to the right.

After the assassination of anti-immigration and anti-Islam politician Pim Fortuyn in 2002 and then of Islam-critic filmmaker Theo van Gogh in 2004, Wilders’ critical views were further strengthened and he was not afraid to voice them, which resulted in his expulsion from the VVD. He founded the Party for Freedom in 2006, of which he is the only formal member. Wilders has been under constant threat because of his fierce anti-Islamism and has been under police protection since 2004, with his house and parliamentary office set up accordingly. The Party for Freedom has been repeatedly considered the most popular party, but in elections, someone has always come out ahead. Between 2010 and 2012, Mark Rutte’s minority government was supported from the outside but was finally weakened in the 2012 early elections and thus retreated into opposition.

After a Quarter of a Century in Politics, Wilders’ Time Has Come

‘The Dutch will be No. 1 again. We will limit the asylum tsunami. People will have money in their wallets again,’ he promised in his campaign. He has also often stressed that he would even ban mosques and Islamic schools in the country, although he has said in the campaign rally that there are more important issues than that for the time being. On the eve of his election victory, he pinned down: ‘We want to govern, and we will govern.’

He even floated the idea of a Nexit referendum if he gets into government,

in which the Dutch people, one of the founders of the European Community, would have to choose between remaining or leaving. Wilders, however, later said that the mood was not right for such a vote.

To form a coalition, Wilders needs to soften his views, as the Party for Freedom, which does not even have a quarter of the seats in parliament, needs more coalition partners to gain a majority. Timmermans and his team are obviously out of the question, while the VVD and the NSC are not categorically excluding Wilders, although they have expressed reservations. Together, the three parties would have 81 MPs, that is, a majority. In another not-so-extreme case, it is also possible that larger forces outside of Wilders and his party would prefer to unite, knocking the winner out of the chance to govern. What is certain is that, in keeping with Dutch tradition, lengthy negotiations to form a government will begin—last time this task was completed in 271 days, but this time it could be even more difficult to come to a conclusion.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.