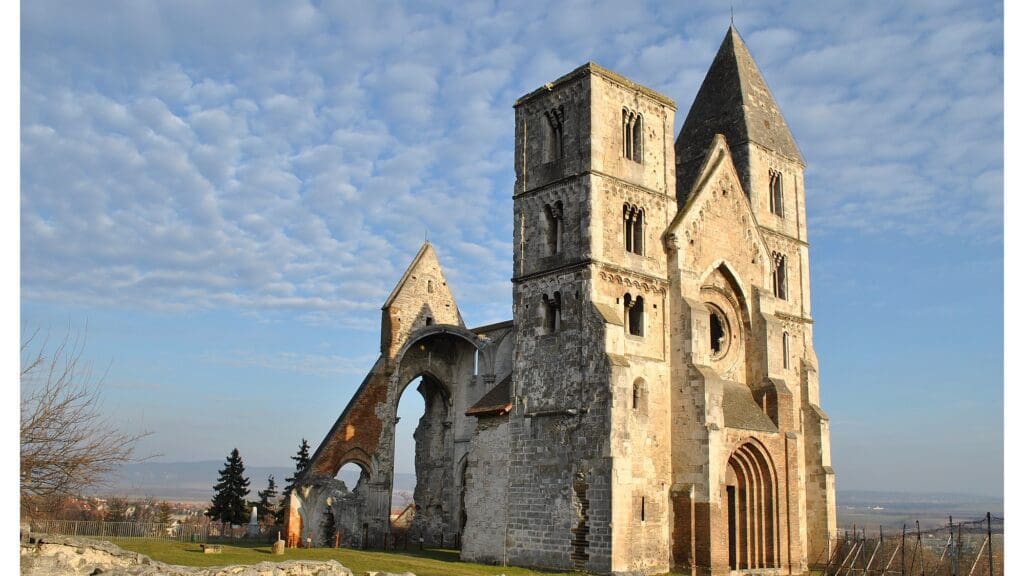

A recently published article by Máté Sibrányi and Gábor Virágos in the cultural magazine Kommentár examines the state of church ruins in Hungary, and also eagerly urges to preserve them. The authors outline that, in order to preserve our culture and heritage, more action needs to be taken regarding ruined medieval places of worship. The article, titled ‘Our Forgotten Churches and Crumbling Bones’, starts making its case by establishing the importance of the protection of our heritage. According to Sibrányi and Virágos, it is a human need, associated with the highest levels of the Maslow pyramid. Therefore, the authors argue, it is also part of what makes humans something beyond biological creatures, and thus it deserves more attention.

Sibrányi and Virágos focus on the ruined medieval churches regarding heritage protection, since, as they see it, these are part of our Christian and national heritage. Furthermore, as the authors of the article put it,

these churches created a ‘spiritual safety net’ for Hungary.

The tone of the piece is generally alarmist. It expresses dismay over the physical conditions of many of our temple ruins, while raising awareness about the need for action in their regard.

According to the article, while churches are essential parts of European and Hungarian landscapes, our medieval places of worship are largely in ruins and remain uncharted. The authors calculated that the contemporary territory of where medieval Hungary used to lie can have over 20 thousand church ruins within. Due to the turbulent history of Hungary, most of these had been destroyed, and 95 per cent of them are standing on territories which are no longer part of the country. The piece also outlines that about half of the churches are uncharted to the extent that we do not even know their exact location.

The article does not offer a clear solution, or even direction. It does admit that fully restoring the ruins would be extremely expensive, and the buildings could often not be salvaged to function sufficiently. However, it still stresses the importance of doing something about our architectural heritage.

It denotes charting and examining these sites as the first action to be taken. The piece warns that if no action is taken, soon it will simply be impossible to restore the old churches to any meaningful extent, since even their ruins will be completely obliterated. Therefore, their only practical advice is that museums and researchers should at least create a topography of the ruins, and chart them for future generations.

The piece goes on to argue that Hungary can be proud of its architectural heritage and church ruins since we have just as pristine a heritage as Western Europe. The authors point to the fact that even the smallest villages had their own churches, on many occasions, great and beautiful Gothic, or otherwise grandiose ones. While the village of Besnyő, for example, had a—now ruined—beautiful Gothic church, it is not mentioned in any sources, meaning that this phenomenon of a village having a splendid shrine was anything but unusual.

It is our turbulent history, not our negligence, which destroyed these buildings,

the authors argue.

Therefore, while the presence of churches like these was not extraordinary, the need to somehow preserve them is extraordinary in its importance, Sibrányi and Virágos claim. They have a message, according to them, a message that our heritage exists, and we have a lasting Christian culture.

Another interesting aspect of the ruins that the piece highlights is that, until the late eighteenth century, cemeteries only existed in the close perimeters of these temples. Thus, almost the full population of medieval Hungary were buried around churches. Therefore, according to the authors, charting their ruins would also enable researchers to identify the remains of many of our ancestors.

The piece concludes by arguing that if we want to preserve our heritage, we must conduct archaeological excavations, topographical research, or other types of examination on the sites of these churches. According to the authors, these ruins are sources of renewal for us and for future generations. Therefore, it is up to the researchers, lawmakers, and other decision-makers whether we preserve this piece of our heritage or not. The authors also remind the readers of how important such preservation operations were for the greats of previous generations, for instance, Hungary’s iconic Minister of Education and Culture, Kuno Klebelsberg. The piece concludes with a quote from Klebelsberg, which is worth keeping mind for everyone:

‘Without culture, there is no Hungary!’

Related articles: