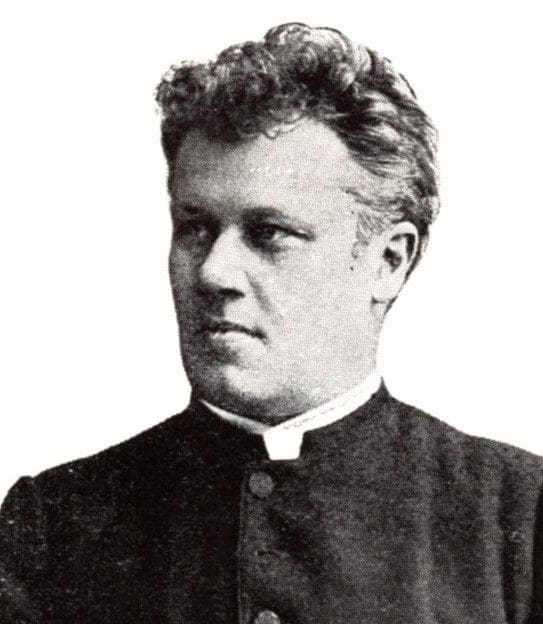

Sándor Giesswein (1856–923) was a man of contrasts. He was a politician as well as a scholar. A man of pragmatism and a man of theory. He belonged to the Roman Catholic Church, but due to his dissenting views, he was relegated to the periphery.

Though this article briefly draws from other sources, its basis is his book titled Social Problems and the Christian Worldview, published in 1907[i]. As can be perceived from his book, Giesswein was one of those theorists with broad theoretical foundations who made their principles part of their practice and political experience. This way, if necessary, experience was adjusted to the theory, and vice versa, his principles paved the way for practical action. He soon became the leader of Christian associations based on German and Italian models, which advertised a Christian worldview. From this movement, he entered ‘big politics.’

Trade unionism, civil associations and political involvement served the same purpose: the representation of and practical advocacy for the ever-growing masses outside his time’s social and political horizons. He was always driven by the challenges of the delayed Hungarian social development and the desire to act to reduce the gap. Thus, in 1905, he first became the president of the General Union of Christian Social Associations, then in the same year, a member of parliament. It can be seen as symbolic that he won the race for MP against a factory owner from Mosonmagyaróvár. In any case, it shows the urge that was increasingly present in Hungarian society at that time to overcome the indifference of contemporary politics to societal demands. As a member of the Hungarian Parliament until 1923, he spoke out in favour of such issues as the amendment of the strike law or compulsory social insurance.

At the same time, Giesswein was also a scholar. He was a linguist, an orientalist, and a canon who wished to defend Catholic teachings with all his intellectual might against the new currents of the era. His work is outstanding since he saw the agrarian proletariat pushed to the periphery, deprived of land and economic progress. Still, he also paid close attention to the spiritual dangers threatening the fundamental transformation of general morality and social development in the dire social conditions of the time.

From the point of view of this spiritual threat, he compares the significant transformations of his era to the fall of the Roman Empire, the discovery of America, or the discovery of mechanical work.[ii] Thus, the internal renewal of Christianity, and the turning of the Catholic Church toward social issues, is also a question of its existence. It is one of the great intellectual battles that would decide the future of European social development. Therefore, when Giesswein talks about the strike law, the guarantee of worker protection within the factory as a politician and organisational leader, it must be examined and interpreted as part of the high theoretical dispute. The essence and centre of Giesswein’s proposition are that ‘Materialistic individualism can have no less consequence than the also materialistic socialism.’[iii] He wanted to protect his country and his church from these dark tendencies.

Considering Giesswein’s critique of socialism, it is crucial to mention a clause that fundamentally influenced the direction of his intellectual efforts. As with several major European currents of thought, it is also true in the case of Christian socialism that it arrived in Hungary late compared to Western Europe. When Christian socialism ‘arrived in’ Hungary, partly thanks to Giesswein, socialism was already present here. Thus the ideological-theoretical superstructure was enriched by the multi-polar ideological field in which he was forced to defend his position.

In his books, Giesswein, although he devotes more space to the refutation of the egalitarian logic of collectivism, throws himself with at least as much radicalism into the denial of the wrong, anti-human approach of extreme individualism and laissez-faire capitalism.

According to Giesswein, collectivism and individualism stem from the same source: their materialism connects them.

This is the historical materialism against which Giesswein argues, on the ground of the Christian image of man and society, which is essentially the fulfilment of the most straightforward commandment of Christianity: ‘Love your neighbour as yourself.’[iv]

Materialism, selfishness as the only social drive, and the overwhelming power of the economy that determines all social development, are all to be equally found in collectivism and in the extreme form of capitalism that destroys the individual and robs him of his dignity, argues Giesswein. Max Stirner, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Adam Smith shared the same view of the national economy; they separated it from morality and placed egoism and egocentrism at its centre. It was the same exercise of the collectivists who developed the concept of economic planning. Behind the doctrine of ‘full freedom of competition knows no other limit than the well-conceived interest’ is the same logic of collectivism, which seeks to create common production and common ownership. They both oppose the idealism and personalism of Christianity.[v] Those who clash with the different forms of collectivism ignore the same factor as their intellectual counterparts, namely human nature and human nature’s tendency to strive for happiness and change. The churchman, who deeply identifies with the teaching of original sin, remarks with the wisdom of a natural politician that while a collectivist society is possible to found, a society that satisfies all human needs and serves the happiness of everyone equally is unimaginable.[vi]

Giesswein was a mediator between the social teachings of the Church and Christian democracy. In his book, he refers to the tremendous Christian social figures of the 19th century. Regarding ecclesiastic leaders, he mentions Ketteler in Germany, Manning in England, and Gibbons in the US. Considering the laic Christians, he appreciates the French count de Mun and the Swiss Decurtins. Altogether, the principles which were based on the teachings of the ancient Church and contributed to the social reform of the 19th century were approved by Pope Leo XIII in his encyclical Rerum Novarum. Not only did Giesswein acknowledge the significance of these developments, but he essentially stood on the ground of these principles. His rejection of Marxism and liberalism, which represent the excessive forms of collectivism and individualism, does not deviate from what was addressed in the Rerum Novarum.[vii] He concludes that Christian socialism, based on Christian ethics, wants to stand in the way of social injustices, caused by overpowering individualism, and promote a healthy social development by implementing appropriate reforms.[viii] Giesswein refers to the fact that the Italians use the term ‘Christian democracy’ and adds that the reason why he uses socialism is mainly out of force of habit.

Furthermore, Giesswein defended the idea of private property and, in contrast to the aulic Catholics, was a devoted democrat, which contributed to the fact that he can be regarded as one of the first representatives of modern Hungarian Christian democracy.

Giesswein clearly understood, which many Christians did not—neither when Giesswein was advocating it, nor later—that the social question is one of the most, if not the most, important questions of modern times. Although Christianity is obviously not only about social problems, it leads to catastrophe if social questions are not considered by it. Being true to his pacifist affinities, one of his ambitions was to mitigate the conflict between the antagonistic worldviews of communism and liberalism by offering a democratically open Christian socialism as an alternative perspective.

This worldview was to serve as a solution to social injustices that spark the conflict. In this regard, Giesswein was a proponent of social justice without being a ‘social justice warrior.’ His theory was grounded in Christian faith which was manifested in the fact that while he fought for social justice with all his might, he always remained a meek ambassador rather than an aggressive soldier. ‘The much-desired social peace can and must be created through social justice’ – he argued in his book.[ix]

By no means are we suggesting that Giesswein was correct in all of his arguments. On the contrary, he can be criticised on several grounds. His biases towards Christianity are probably the most visible, even from a Christian perspective. Everything that Christianity professes is correct, if not the truth; there is no mistake in it, the reader of this book would undoubtedly feel. Naturally, considering his vocation and the general doctrine-centredness of Catholicism, this is not surprising. Yet, especially from today’s perspective, it is disturbing that he only recollects those fragments from Christianity that underpin the conclusions of his arguments.

Consider the case of feminism.

Giesswein was ahead of his time, especially in church circles, with his openness to feminism.

He treated feminism as an indispensable question that should be discussed as part of the general question of social justice. Simply put, feminism is not exclusively the question of women; it must draw the attention of the whole of humanity ‘because the future of social and national developments depends on it.’[x] Moreover, he cites the words of Brunetiére, who argues that if everyone were an honest Christian in the way that serving one’s neighbour is related to the great idea of serving God, then everyone would also be a democrat and a feminist. [xi]

It should be clear that Gieswein proposes Christian feminism, which is based on the idea of equality but not the uniformity of the sexes; the protection of womanhood (thus motherhood), and of traditional marriage. Without delving into a conceptual debate with Giesswein on the values of Christian feminism and their relation to other forms of feminism, which are always affected by contrasting presuppositions, his method should be questioned. He argues that Christianity contributed to abolishing the Eastern or Asian conceptions of women being inferior to men. He refers to Biblical texts and ancient scholars to justify his claim that Christianity acknowledges women as equal. Consequently, he criticises the materialistic conception of feminism and endorses Christian feminism to avoid the injustices which affected women through romanticism and naturalism.

No matter how much Giesswein’s feminism is to be appreciated, he should have probably engaged in some introspection as well. We could find plenty of examples of how, if not Christian principles, but at least historical Christianity contributed to the injustices affecting women. Of course, one can always argue that the injustices resulted from the non-observance of Christian principles (as, for example, Giesswein denies the symbiotic relationship between feudalism and Christianity). Still, even then, it would be more sympathetic and expedient to analyse the reality and those Biblical passages which do not underpin, at least at first glance, his general argument. In any case, a couple of quotes from the Bible and from ancient authors alone in no way prove that historical Christianity treated women as equals and did not contribute to the injustices which affected them.

To sum up, Giesswein’s position can be framed as an alternative middle road between socialism and liberalism. As he himself put it, the ‘middle ground of truth falls far both from the far right and far left.’[xii]

However, this does not mean that he was a man who agreed with everyone to a certain degree. Christianity rejects social injustice, both the collective and individual forms of it, and the idea which connected Communism and liberalism, namely, materialism. If there was anything he wished to accomplish with his book it was undoubtedly what he mentioned in the preface and in the conclusion: that idealism, especially the Christian version of idealism, should gain victory over materialism. In this way, his purpose made him accepting: ‘Everything that enhances this idealism moves man and humanity forward, and everything that attacks this idealism and weakens it leads to decadence.’[xiii]

[i] Sándor Giesswein, Társadalmi problémák és keresztény világnézet, Budapest, Szent István Társulat, 1907.

[ii] Giesswein, Társadalmi problémák és keresztény világnézet, 23.

[iii] Giesswein, op. cit. 40.

[iv] Giesswein, 7.

[v] Giesswein, 35.

[vi] Giesswein, 80

[vii] Giesswein, 111.

[viii] Giesswein, 46.

[ix] Giesswein, VIII.

[x] Giesswein, 129.

[xi] Giesswein, 130.

[xii Giesswein, 6.

[xiii] Giesswein, 172.