In November 2022, I attended the opening conference of the new Brussels branch of MCC, a Hungarian think tank that has gone international in the past years and is on its way to becoming the intellectual hub for continental conservatism.[1] Great scholars from all over Europe were present to debate the current state and future trajectories of conservative political thought within the EU and to draw inspiration from each other’s perspectives. Without doubt, the liveliest discussion of the event was about Hungary: what makes it so unique and yet so successful? What is the secret of the Hungarian model? As I listened to the dozen or so renowned international figures expressing their genuine admiration for the Hungarian political system, I realized that Hungary truly is exceptional in some ways and that I had taken it for granted for so long. After all, it’s not a given that a government implements policies that go so radically against the current liberal zeitgeist yet still manages to stay more stable and popular than any of its Western contemporaries. It feels natural for us in Hungary but needs explanation elsewhere. Fortunately, that’s exactly what Balázs Orbán, the political director of the prime minister,[2] set out to do in his book, The Hungarian Way of Strategy.

Throughout the book, Orbán uses several metaphors, jokes and parables to make his inherently scholarly reasoning more digestible. The one that is meant to demonstrate the question above (how can Hungary be successful while being under constant attack from abroad?) is the one about the flight of the bumblebee, which has been borrowed by PM Orbán himself.[3] Scientists were for a long time puzzled by the insect, for according to all of their existing models, the bumblebee should be unable to fly due to not having large enough wings for its mass. Only after the development of its observational tools could science solve this conundrum: the unique texture and movement of the wings create a ‘hidden turbulence’ to keep the bumblebee airborne. The author posits the post–2010 Hungary to be in a similar situation: a tiny nation pulling above its weight, which—by all rules of the liberal democratic mainstream—should have failed a long time ago yet its unique character keeps it going term after term. If the existing models fail to explain a phenomenon,

the bumblebee reminds us that it is the models that are incomplete, and alternative ones should be explored.

But before we delve into the depths of that alternative—the seemingly only viable alternative to liberal democracy, or the Hungarian way of strategy, if you will—we first need to examine the road that led us there, the intent and circumstances that forged it. The premise of Orbán’s book is that the generation that’s at the helm of politics today found itself at a pivotal moment in history. A brief, once-in-a-lifetime moment when small states like Hungary have enough room for maneuvre to construct their own strategy. Understanding this not only as an opportunity but a responsibility, this group of politicians sat down at the beginning of the 2010s to identify the unique markers in Hungarian history that could be turned into strategic principles that last for decades. What followed under the subsequent Fidesz governments was the implementation and fine-tuning of those principles, until the world started to take notice of the now crystalized ‘Hungarian model’.

‘Finding the Right Balance Between the Means and the Ends’

The structure of the book makes reading it feel like going through the steps of solving a math problem: it is precise, logical and common-sensical at every turn. The book has four chapters, each falling into place like puzzle pieces, to eventually join together in the final formulation of the Hungarian strategy.

The first chapter—the most theoretical and therefore the most engaging to someone intrigued by political science and philosophy—is all about the keyword of the book: strategy. In it Orbán turns to a vast collection of scientific literature in his attempt to define the term with all the relevant whys and hows. What is a political strategy, why do we need long-term plans, how are we to begin and how do we avoid the most common pitfalls when devising one? After distilling the essence of the knowledge passed down since the antiquity and through the works of the greatest scholars of our time, he arrives at one basic thesis. ‘The true art of strategizing lies in finding the right balance, somewhere between the twin poles of means and ends: what means can I use to attain my ends, and what ends are attainable with the available means?’[4] In other words, we are bound to fail in constructing a lasting strategy both by planning without setting ultimate goals and by setting goals that will prove to be limited to due to internal or external circumstances.

A good strategy, therefore, rests on two pillars: the strategist and their circumstances.[5]

Only by attaining deep knowledge about the inherently present ways and obstacles in both—factors that propel us toward or prevent us from reaching our goal—can we even attempt to formulate one.

The second and third chapters are devoted to the formulation of strategies. The second chapter provides a brief overview of world history since the end of the First World War that culminates in our present day. This allows the author to show us ‘how the horizon of strategic thinking narrowed during the 20th century and expanded in the 21st.’[6] In perhaps a bit overly simplistic but otherwise quite consistent manner, Orbán demonstrates that at every major turn, the consecutive international systems of the last century put most powers—small or great—on already pre-ordained paths with not much room for manoeuvre. This was true of the revisionist decades set by the Treaty of Versailles, the bipolar world of the Cold War and also of the unipolar culmination of the Pax Americana, periods that Orbán calls the ‘reign of the dominant paradigm’[7] in the ‘90s and 2000s. But as the power of the West—and with it, the appeal of liberalism—started to erode in waves after 9/11,[8] the paradigm also loosened, giving smaller states a rare window of opportunity to formulate their own strategy.

When describing the internal circumstances, that is one’s own abilities and limitations, Orbán turns to history once more. The far-from-smooth transitions of former Warsaw Pact countries to liberal democracies in the 1990s showed us that taking an existing foreign model and implementing it without taking into account the unique local characteristics amounts to strategic suicide. Therefore, in order for any country to devise a viable strategy of its own, it would first need to look back at its history and identify the markers that could serve as the basis of its future. Now, this third chapter on the history of Hungarian statecraft starts from the very founding of the Hungarian Kingdom at the beginning of the 11th century for a reason. Originally a lawyer, Orbán dwells long on explaining medieval Hungary’s constitutional principles which, similarly to the British, evolved organically throughout the centuries. Then, connecting to the unique aspects of Hungarian common law, he identifies episodes in our nation’s history that are descriptive of the Hungarian character, to ultimately produce a list of qualities on which to base his strategy later. The author divides Hungarian history into two parts: the first (11th–15th century) is mainly characterized by responsible statesmanship, well-balanced legal development, internal stability and peaceful expansionism for the sake of Central European security; the second (16th–20th century) is marked by the endless struggle for sovereignty and self-determination in the shadow of empires. This stark contrast illuminates the message perfectly:

Hungary flourishes when left alone and thus will never accept foreign yoke—whether literal or metaphysical—again.

Therefore, this love of freedom, among others,[9] is an inherently Hungarian trait that cannot be overlooked when devising a Hungarian strategy.

The fourth and longest chapter discusses the Hungarian way of strategy, as formulated after taking all the above-mentioned factors into account and as implemented by the post-2010 Hungarian governments. The chapter has two main parts: one on the cornerstones of the Hungarian model (policies and their results so far) and another one on the values that serve as their ultimate rationale. The secret of the Hungarian model, according to Orbán, is that all policies are fundamentally based on eternal social values distilled from a thousand years of historical experience. In contrast to the liberal democratic model— which explicitly avoids the endorsement or disapproval of any social values lest for the detriment of minority groups that do or do not share them, whether beneficial or harmful—the Hungarian governments ‘have proven no strangers to value-based politics’, Orbán argues. ‘The Hungarian interest, and the previously submerged cornerstones of Hungarian strategic thinking, all return in some form or another to these underlying foundations. This is precisely why the government has so often been branded “anti-democratic”: from the point of view of a liberal democrat, to endorse a particular value is to dictatorially impose it.’[10] And this is also what makes Hungary the bumblebee of Europe: it dared to envision and implement its own model instead of following something designed by and for others. It then filled that model with value-based policies and was still able to solidify public support behind it. The trick is simple: the values in question are both integral parts of the Hungarian character and beneficial to the Hungarian nation.

Finally, Orbán compiles nineteen points—values, truths and basic tenets—that make up the current Hungarian strategy. To mention just a few, these points include the family being the most fundamental unit of society (a view expressed in tax cuts, subsidies and a whole range of family policies). Another point is that the nation is the highest-level entity with a shared identity, which is the rationale behind strengthening national culture and limiting mass immigration. The idea that the state should prioritize Christian values for the benefit of society while respecting citizens’ personal autonomy and freedom; that the state is the ultimate representative of national interests through its democratic institutions and that, consequently, the preservation of Hungary’s national sovereignty is its most important and permanent goal are also among the key points of the strategy. These observations do feel like common sense in Hungary now, but—judging by the state of European politics today—I doubt it would be the case without the Orbán government consistently standing up for them even in the face of endless criticism.

‘The Enemy of a Good Plan is the Dream of a Perfect Plan’

Now, the question arises: does The Hungarian Way of Strategy have a genuine scholarly merit? Can it pass the test of time and stay relevant long after the Orbán government is gone? Are the cornerstones of the Hungarian strategy outlined in it so universal that they can be viewed as a lasting guideline for future Hungarian establishments? Is it truly a strategy or just a rationalising description of the current Hungarian model?

Truth be told, The Hungarian Way of Strategy is not a strictly academic work, nor is it just a political manifesto. It is somewhere between the two, without claiming to be something that it isn’t. The author makes it clear from the start that he will not attempt to present any truly objective take on Hungarian statecraft;

the book’s very purpose is to present the perspective of the government in an unprecedentedly in-depth way.

It is the success of the already existing Hungarian model that it wants to explain, after all, and not devising a strategy from scratch that is completely taken out of the current political context.

It would be equally untrue to claim that the book has no scientific foundation. In fact, anyone familiar with the author would know that he’s never considered himself a true politician—in heart, he’ll always be an academic. The Hungarian Way of Strategy draws from an impressive bibliography comprised of more than three hundred titles. Among these, we find the greatest names in political and philosophical literature (such as Kissinger, Gaddis, Huntington, Spengler, Strauss and Scruton), but Orbán also consults the timeless works of more ancient history (Marcus Aurelius, Sun Tzu or Machiavelli). Furthermore, Orbán often gets to the bottom of liberal arguments, too, discussing them in detail and reflecting on their merits (such as those of Popper’s Open Society and its Enemies). Finally, when he’s discussing the Orbán government’s deliberate appropriation of the term ‘illiberal democracy’[11] and the frequent accusations of being ‘anti-democratic’ or ‘authoritarian’ in its approach, the author provides a whole list of critical literature.[12]

There is only one aspect of the Hungarian strategy that I felt the book does not sufficiently elaborate on: geopolitics, which is only briefly touched upon in the last chapter in relation to Hungary’s foreign policy. Towards the end of the book, Orbán discusses the need to preserve sovereignty within the institutional framework of the European Union, as well as the importance of regional cooperation and Hungary’s role in the various Central European constellations.[13] But the book barely discusses regional security, something that has grown in importance significantly since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Of course, at the time of its writing, the conflict was still beyond the horizon and not even an experienced statesman such as Balázs Orbán could have predicted what 2022 brought. Nonetheless, a second edition of the book or complementary writing on Hungary’s geopolitical, security-driven strategy would be most welcome.

But all in all, the book, I believe, will in time find its place among the most important works of Hungarian political thinking and remain there for decades or even centuries. Balázs Orbán’s work is a penetrative exegesis of the unique success of Hungarian statecraft in the past decade as well as an astute guide for all nation-states of similar stature.

The Hungarian Way of Strategy is a beacon in the fog of our ideology-driven era,

meant for those whose understanding of time goes beyond the fleeting moments of the present. For now, it is ‘merely’ an insight into the uniqueness of the bumblebee’s wings, but in the future, it could serve as the handbook not only of the rebuilding Hungarian statehood returning to its original foundations (should it ever wander off track again), but also as a ‘Baedeker’ for those of any nationality who wish to see their countries stand on more solid ground than the hollowed-out principles of liberalism. The book is also an important contribution to the efforts striving for a value-based political reformation of Europe, for the secret of surviving the millennium ahead of us on this continent is to learn from the knowledge of the one behind us.

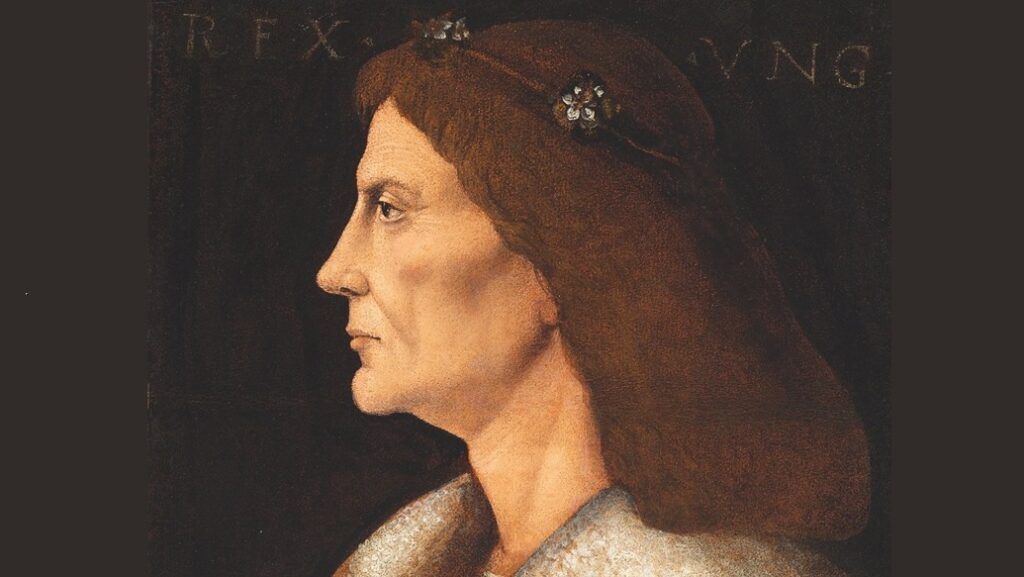

[1] The Matthias Corvinus Collegium (MCC) was founded in 1996 with the aim of providing complementary education to young people interested in bettering the future of Hungarian public discourse. By now, MCC has grown into Hungary’s largest think tank and political research institute, with more than four thousand students enrolled in its various programmes at over two dozen branches across Europe.

[2] The author’s remarkable political career is well worth mentioning. In 2013, at just 27, Orbán—after earning his PhD in law—became the research director of Századvég, one of Hungary’s primary political think tanks, then two years later he was invited to lead the newly-founded Migration Research Institute. In 2018 he was appointed deputy minister in the fourth Orbán government as well as state secretary for strategic issues. Since 2021, he has worked as the political director of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, overseeing the work of the highest-level advisory board in Hungarian public life.

[3] Balázs Orbán, The Hungarian Way of Strategy, MCC Press, Budapest, 2021, p. 171.

[4] Orbán, p. 10.

[5] Orbán, p. 38.

[6] Orbán, p. 53.

[7] Orbán, p. 59.

[8] The uncontested rule of Western liberal democracy did not come to an abrupt end but is slowly haemorrhaging to this day. The attacks on the WTC in 2001 showed that at least certain parts of the globe, even if relatively underdeveloped, can and do reject American hegemony. Later, the 2008 crash made it apparent that the Western economic system is far from infallible and, if followed blindly, can massively damage all other economies as well. The 2015 migration crisis exposed the widening divide between Western elites and ordinary citizens, while Brexit and the election of Donald Trump—in the broader context of the culture war—testified to the direct consequence of the divide: the rejection of liberal values by a large part of the citizenry. According to Orbán, it was this series of events that truly started the transition from a unipolar to a multipolar world. (Orbán, pp. 73-80).

[9] For instance, Orbán’s list of elements of ‘Hungarianness’ (p. 118) also includes scepticism of foreign ideas and the ability to reshape them in its own image; being a cultural blend between East and West; being eternally divided over certain issues yet remarkably united when facing external threats; or the inclination to give Christianity an important role in political life.

[10] Orbán, p. 138.

[11] The term was originally coined in a Foreign Affairs article in 1997 by Fareed Zakaria, who used it in a purely pejorative sense to describe a form of mild, subtle authoritarianism. In the sense that the Orbán government is using it to describe the current Hungarian model, however, is to signal the ‘non-liberal’ aspect of its ideology and to draw attention to the fact that the terms ‘democracy’ and ‘liberalism’ are not necessarily inseparable. In this view, ‘illiberal democracy’ does not, in any way, mean the erosion of democratic principles, but quite the contrary: it denotes a democracy that is free from the burden of liberalism. (Orbán, p. 79).

[12] Orbán, p. 135.

[13] Orbán, pp. 179-183.

[14] Orbán, p. 149.