Military experts and analysts are closely examining the war in Ukraine, using the experience of the battlefield to draw conclusions about how future wars will look like. While many are calling for a revolution in warring, the reality may not be that the war in Ukraine will bring radical change in the way the war is fought, Stephen Biddle argues in Foreign Affairs.

The proliferation of advanced technology on the battlefield in Ukraine, such as surveillance from space centres, precision weapons, networked communications and hi-tech drones, has quickly led military analysts to conclude that we are witnessing a long-overdue transformation of war. A transformation in which ubiquitous intelligence, artificial intelligence and hi-tech tools render ineffective the mass deployment of conventional arms such as tanks and heavy artillery. Drones, artificial intelligence, and rapid adaptation of commercial technologies in Ukraine are creating ‘a genuine military revolution,’ an a recent insightful piece in Foreign Affairs quoted military strategist T. X. Hammes.

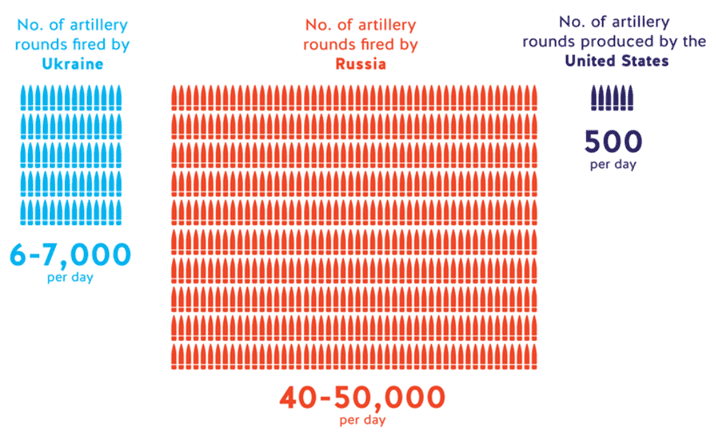

But reports from the battlefields of Ukraine also report on thousands of scattered landmines, infantrymen digging in mud and trenches, and millions of rounds of artillery shells fired, while the military industrial capacity of both Russia and the Western nations supporting Ukraine has been overstretched by the depletion of munitions. Last year, it was estimated that by the summer of 2022, Ukraine was firing 6–7,000 155mm artillery rounds per day in the Donbas region while Russia was firing 40–50,000 daily. Meanwhile the US was capable of producing 15,000 155mm rounds a month (!). All this is definitely more reminiscent of the the wars of the last century than a so-called high-tech war fought from control rooms and space.

Source: United States Studies Centre

So, the question arises: how different is the war has been fought in Ukraine from the wars of the past? The author suggests that although we see new tools on both sides of the war, the outcome is not really changing, and what we are seeing is more about the gradual introduction of new weapons and methods into the war rather than a tectonic transformation of the war itself.

Mr Biddle uses a number of examples to illustrate why assertions of the obsolescence of conventional military tools in the face of modern, precision weapons and surveillance equipment are misleading. For a start, the argument that these tools and procedures have made the battlefield much more deadly is refuted by the rate of destruction of tanks. Although both Ukraine and Russia lost more than 50 per cent of their tanks compared to the number they had at the beginning of the war—Russia lost somewhere between 1,600 and 3,200 of its 3,400 tanks, while Ukraine lost 459 of its 900 tanks in the first year of the war—

this ratio does not seem out of line with the war losses of the last hundred years or so.

In the Battle of Amiens, for instance, the British lost 98 per cent of their tanks; Germany lost 113 per cent in 1943 and 122 per cent in 1944 of the tanks it had at the beginning of the year. Fighter aircraft losses or artillery damage in Ukraine are also not outstandingly high compared to similar figures in the First or Second World Wars.

The new, modern equipment and lethal weapons have also not brought about the drastic change in the pattern of war that many expected, resulting in a defensive stalemate rather than territorial offensives. This is borne out by the fact that in the first phase of the war, both the poorly executed Russian offensive and the Ukrainian counter-offensive were able to seize significant territory, but offensives in Kyiv, Kharkiv and Kherson are no indication of a defensive stalemate. ’The war has thus presented a mix of successful offense and successful defence, not a pattern of consistent offensive frustration. And all this — both the breakthroughs and the stalemates — has occurred in the face of new weapons and equipment,’ Stephen Biddle underlines.

It could be argued that modern tools and methods are part of what shapes the outcome of war, but not the decisive factors. Thus, how the parties use their own tools and anticipate those of the enemy is also of great importance. This mutual impact of technological measures and countermeasures can be seen in Ukraine as well. To give an example: expensive and advanced drones were destroyed by guided antiaircraft missiles, which encouraged fighters to use cheaper drones in larger numbers. Later, these have been thwarted by simpler and more affordable antiaircraft artillery and portable jammers. Furthermore, the combination of different tools and combat techniques also contributes greatly to the effectiveness of these modern assets. Depth defence, mobile reserves and a coordinated combination of forces including infantry, tanks, engineers and air defence are needed. If the new, modern and often expensive equipment is not coordinated and properly integrated with the ‘old’ one, its effectiveness could be greatly reduced.

In conclusion, the author suggests that

the war in Ukraine represents an evolution rather than a revolution in warfare

and fits into the trend of linear evolution of war proven by the factors analysed above. As we witness a development and not a revolution in warfare, there is no sense of urgency regarding the radical replacement of tanks or a complete replacement of infantry by robotic systems. Nevertheless, Western countries do need to invest in the acquisition and development of modern weapons, the author stresses, and should also renew their military doctrines from time to time, to integrate and harmonise new tools and methods.

Hungary’s force development programme in fact continues in line with that concept, incorporating the lessons learned from the war in Ukraine, while the country’s defence budget will reach 2 per cent of GDP this year. As part of the modernisation, the Hungarian Defence Forces (HDF) can get rid of obsolete technology and receive modern weapons and equipment such as Leopard 2A7HU battle tanks, Lynx KF41 infantry fighting vehicle, Airbus H225M medium helicopters or PzH 200 self-propelled artillery. In addition to the modern, but already well-proven heavy military equipment, innovation and digitalisation are also a major focus for the HDF, while special attention is paid to training, so that the Hungarian army can use the new equipment properly integrated in the most effective way with qualified personnel.

Related articles: